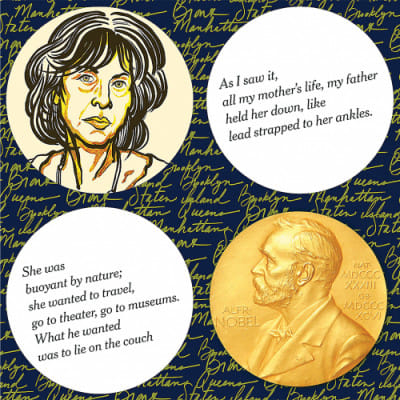

On discovering the poetry of Louise Glück, Nobel Prize in Literature 2020

I was waiting on October 8th to see if the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature would be Murakami. It had become a joke by then, his missing the prize, but I thought maybe, just maybe he'd win this time. He didn't. But after the Bob Dylan incident of 2016, I got over this quick. The winner was Louise Glück, an American poet little known outside America but with several accolades to her name.

The first poem of Glück that I came across was "Gretel in Darkness". In it, Gretel is safe, well-fed, guarded away "from women's arms", but haunted still by the murder she has committed ("Why do I not forget?"). There was something strangely enchanting about the feelings and images she conjured, so much so that the fear was as palpable and fresh as it might've been on the day Gretel and her brother were asleep in the witch's hut, vulnerable children left to fend for themselves. The poem stuck, and I looked for others.

I then started with "A Fable" which speaks of two women claiming the same baby as her own. The story was a well-known one, but on the 9th line, other meanings seem to surface between the line breaks. "Let the child be/ cut in half; that way", Glück wrote, and I wondered if by "Let the child be" she meant to let the child go. Or was she referring to something even more gruesome, such as that the child ought to be sliced?

I read on, and by the 19th line there came a sharp twist. Like "Gretel in Darkness" before it, there on the screen was an age-old story in a new light. The tale turned into one about a mother ("your mother" she writes as if speaking directly to me) "torn between two daughters" where one must self-destruct to protect the mother. And images flashed in my mind of a favoured daughter and a less preferred or even loathed one, in movies, in books, in the mother holding the hands of two little girls as they walk to school. The poem seemed unfamiliar for many reasons, but what stood out most was the shocking sparseness, and I wondered if the lines hadn't been strikingly short, would they still retain this magical quality?

I was answered when I read another of her poems with longer lines, titled "Celestial Music", where expectations are reversed by the second line. "I have a friend who still believes in heaven", Glück writes in the first line. Immediately after, we're told that this isn't exactly the kind of child who is childish or too innocent, but a more pragmatic one. The meaning remains elusive, making it difficult to summarise. Alongside that is the imagery, wholly unusual and captivating, shifting from two friends looking at ants slowly devouring a dying caterpillar to a list of commonly white things such as clouds and snow and then a new one with "a white business in the trees/ Like brides leaping to a great height".

Louise Glück's poetry is at once deeply personal and ubiquitous. Articles explaining her work demur from calling it confessional, and they may be right. It doesn't feel like the thoughts and feelings of another; the speaker confessing seems more vulnerable, as if they're opening up particularly to you. The sceneries she weaves are odd and alluring, and behind the deceptively simple lines are layers of meaning. One might find common images and themes--death, darkness, gardens, and winter, but one should also know that in her poems, winter isn't just a season and form is more than shape. Her poems are like ponds that reveal a different shade of water when you dip your hand in, and the surface ripples away to reveal something else. And her words stay, settling slowly inside you so when you lie in bed about to fall asleep. Your mind might drift and you may imagine a flurry of white cloth in the sky, or wonder how a witch's tongue would evaporate.

Aliza Rahman is a contributor for Daily Star Books.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments