A family comes undone in Leesa Gazi’s ‘Hellfire’

Bright and cold on a winter afternoon, in the hours leading up to lunch, the kitchen of a Bengali family sizzles with tension. Refrigerated meat is thawed and spices are crushed and pestled. Dishes are washed, helpers are yelled at; some long-standing house rule is suddenly excused amidst the domestic chaos, and unspoken trauma and resentments are pressed back down even as they threaten to bubble over like the brown and green-flecked ochre daal simmering on the stove top. We know this scene—we've lived it—and like a fly on the wall we watch it unfold in Farida Khanam's Monipuripara home on the afternoon of her elder daughter's 40th birthday, when Lovely has been allowed out of the house alone for the first time. In Leesa Gazi's words, translated from the Bengali by Shabnam Nadiya, this day will imprint itself upon the minds of Farida, Lovely, her sister Beauty, and the readers watching. Hellfire (Westland Publications, September 2020) is a slim and delicious novel.

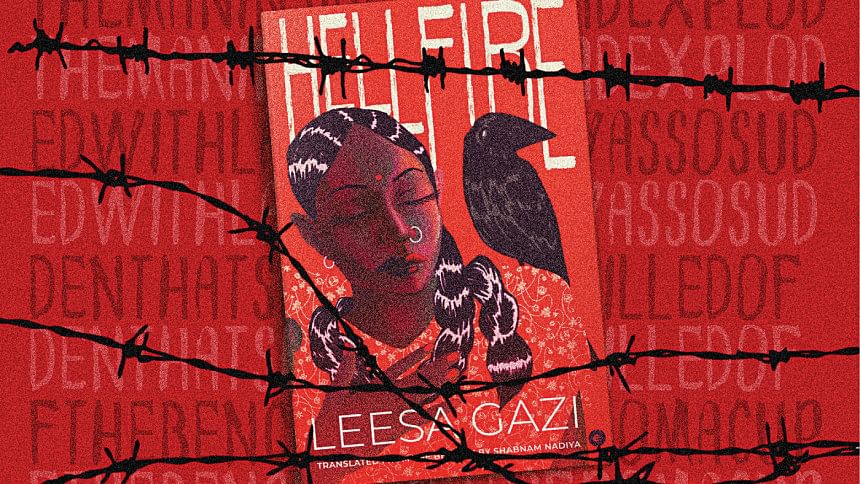

To experience the trivialities and intricacies of Dhaka life in book form—one that reads well and looks good—is a rare treat for English readers in Bangladesh. The fault for this mostly lies with local publishers, many of whom spare little attention to cover art, formatting, or editorial work that goes beyond proofreading. It's not for readers to know how much editorial input Hellfire contains, but the finished product is a well-edited book. The ominous red and black cover promises a potent, seductive read, and the text delivers. The formatting is as neat and concise as the story it illustrates.

And the content itself is clearly the brainchild of an author-translator duo who have fingers placed on the very pulse of domestic life in this country. Leesa Gazi has been known to meld dual worlds in her previous works: both writing and directing Rising Silence (2018), a documentary about the lives of Birangonas, and reimaging Dickens' Oliver Twist as a modern day, female-centred Aleya Twist (2019). This time, she goes entirely local, and the constraints of setting, form, and medium produce fascinating results, mirroring the intriguing effects of imprisonment upon her novel's characters.

Hellfire is at once a book about patriarchy that bleeds into and invigorates a toxic type of matriarchy, and also a book about freedom, desire, and the possibilities of human nature. Lovely and her sister Beauty haven't been allowed to socialise, attend school, or even find spouses as they approach middle age, all because their mother Farida feels the need to control her household: "My house, my siblings, my parents—this concept of mine was dangerously alive in her." But just when you begin to despise her for the demons she has helped create in her girls—which incidentally make them fascinating creatures to read about—the text suddenly changes dimensions. If not a rationale, one is now offered a deeper, riskier glimpse into what tied this family up into such ugly knots in the first place, and the causes are sadly all too prevalent in life outside of the book's pages in our society. The finesse in Hellfire lies in how realistically it portrays such crossed wires as they must look from afar, undisturbed on an afternoon packed with chores and winter heat, and how ominous they become the closer one steps. Dramatic elements notwithstanding, the novel captures perfectly the convoluted blueprint and precarious balance holding up nearly every average family, particularly one situated in a South Asian society.

All of this it accomplishes in less than two hundred pages. Tahmima Anam, whose blurb endorses the book on its cover, has pointed out the traces of Greek tragedy in Leesa Gazi's characters. But it's hard not to also be reminded of Mrs Dalloway. Like Virginia Woolf's novel, Hellfire opens with the promise of a lunch (instead of Clarissa's dinner) party and takes place over the course of one seemingly ordinary day. Like Woolf's characters, Gazi's go about their respective businesses—Beauty applying her face masks, Lovely heading out to Gawsia and Ramna park, Farida busy preparing the luchi, duck curry, raita, and hilsa polao on today's menu, and Mokhles Shaheb dosing over his tea on the balcony—until suddenly, the tethers roping them all together are stretched tight, and an unravelling is set into motion. And like Woolf's war-haunted, early 20th century England, Hellfire is cheekily grounded in the socio-political landscape of contemporary Bangladesh. Struggle too hard against the powers that be (Farida in this case) and you "might be remanded into custody. You might even be finished off in a crossfire."

Some books deserve language that functions as an independent entity, language that soars and dives and distracts you from the minutiae of the story. But here, in a book whose characters and tightly choreographed plot are the stars, Shabnam Nadiya's translation floats like charged air—transparent yet propulsive. If one had to nitpick, I'd say I would've wanted to see Lovely see more and do more around the city. But it's also easy to see why she stays within the boundaries that she does. Either way, throughout her mini adventure, you sit biting your nails over what might happen next, which could be anything, until the thrust of a climax brings you up short, leaving a disturbing, mildly nauseating flavour in its wake.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at @wordsinteal on Instagram or [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments