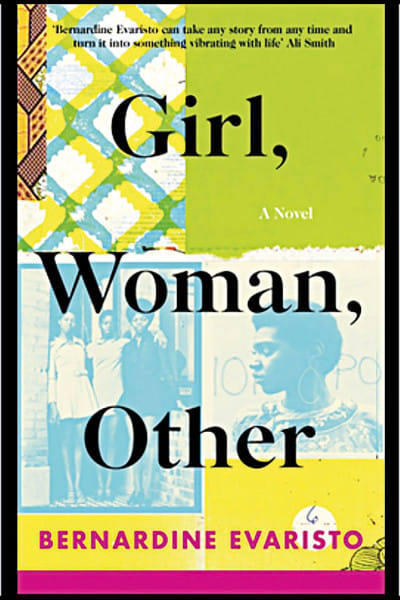

Girl, Woman, Other: A Review

Girl, Woman, Other by Bernadine Evaristo is a beautiful rendition of the intertwining lives of people in modern Britain. Twelve people, most of whom are women, each dedicated a chapter, are seen in the best and worst moments of their lives. From Amma Bonsu, "Queen of the Dykes" to Penelope, a semi-feminist schoolteacher, from Winsome with her sexual obsessions about her son-in-law to Megan/Morgan who finds themselves by "travelling into the batshit-crazy end of the Transgender verse" published at the beginning of May 2019 and Atwood's co-winner of last year's Booker Prize, Evaristo's latest novel has been described as a polyphony of female voices, mostly black, coming together to retell the experiences of a black modern Britain. Polyphony is certainly the correct term for a novel that casts twelve main characters, each telling their story, each with their own take on sexuality and gender, each of a different shade of "black," spanning from the nineteen year old Londoner Yazz to the ninety-four Hattie, who has lived all of her days in a rural mansion in the northern English countryside.

Evaristo has very cleverly sketched characters that are relatable and complex, with stories that will break your heart and make you smile. She has tackled issues faced by most women in their day to day lives, regardless of color and societal position. As the interconnected stories of the twelve main female characters unfold, the reader will be quick to judge that the there is no one black Britain emerging between these pages, and intentionally so – Girl, Woman, Other is not so much about femininity and blackness as it is an episodic deconstruction of whatever preconceived perception we might have held of these.

The first woman we meet is Amma, a "sixty-something dyke" who has been a feminist activist in the eighties when she ran the Bush Women Theatre Company together with her dearest friend Dominique (also a lesbian, but "uber-cool," as Amma defines her, and an intersectional feminist). After a lifetime of attempts to get her artistic struggles the attention they deserved, Amma's most recent play – a lesbian take on an eighteen century royal England – The Last Amazon of Dahomey about to open at the National theatre, is sold out, and expected to be attended by over a thousand spectators.

Among these we will find some of the main characters: Yazz (Amma's extraordinarily self-confident and explosive daughter, always surrounded by her squad of "unfuckwithables" friends), Dominique (who flew back from America for the occasion), Shirley (one of Amma's closest friends, a feminist, but, according to Dominique, a homophobe), Carole (who ends up at the play's opening because her husband Lennox has to attend it, but had also been Shirley's high-school pupil) and Morgan (previously Megan, now the renowned influencer/trans-worrier, non-binary, pansexual going by the pronoun "they", whom Yazz has met at a University conference).

With a full black female cast and performed in a "fan-shaped auditorium, modelled on the Greek amphitheaters that ensured every-one in the audience had an uninterrupted view of the action," Amma's play seems to act as a frame to Evaristo's polyphony of voices and emulate the novel's structure and mode in a parallel montage. This is particularly apparent when one considers the writer's choice to close the novel with an Epilogue, which not only adds a thematic sophistication at the novel's end but concurrently places it in the tradition of Greek tragedies as well.

Girl, Woman, Other is written in the style of a prose poem which Evaristo has termed "fusion fiction," Apparently uttered in the voice of a third person and defiant of the traditional usage of punctuations, the text reads like a collection of monologues, where the line break may simply replace a common full stop and signify a shift in the perspective of a narrator:

"The fluid way in which I shaped, lineated and punctuated the prose on the page enabled me to oscillate between the past and the present inside their heads, outside their heads, and eventually from one character's story into another character's story."

Evaristo manages the prose well and unceremoniously, moving nimbly through different registers. Her narration is to the point, experimental enough to feel new but always careful to make itself accessible to all readers. The unconventionality of the prose is eye catching and surprisingly easy to read. The idea behind the book, of the intermingled lifelines of women, however, is not as original as those of other prominent black women authors like Gloria Naylor and Toni Morrison who have already explored it before. However, the execution of the trope, the narrative style, and the profound connection between the characters are brilliant. Not only complex concepts like identity, sexuality and race have been traversed, but also other equally problematic issues as in politics, empathy, and pretentions have been duly observed and successfully communicated.

Standing between poetry and prose, between fiction and drama, Girl, Woman, Other seems to argue that everything we think we can pin down to definite categories and phrasings – traditional literary forms, gender, sexuality, blackness, religion, even feminism – lay haphazardly on a spectrum. In a time that requires that we learn to make well-informed judgments, it is unsurprising and refreshing that Girl, Woman, Other was awarded the Booker Prize, making Evaristo the first black woman writer ever to win it. Leaving prize selections and winning speculations on the other side, I agree that Evaristo's novel is not undeserving of its attention and attainments: like Yazz says of her mother's play, Evaristo's novel goes "down like a lead balloon" – beautifully crafted and heartfelt, although some may find the material a little hard to digest.

Sahid Kamrul is a Research Fellow at Freie University Berlin, Germany.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments