How 1952 paved the way for 1971

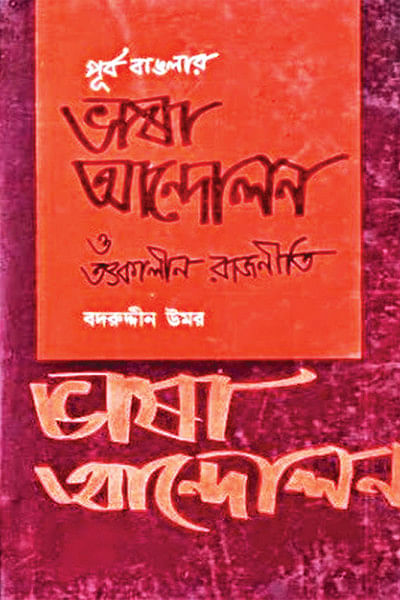

Many historians have often argued if the entire self-determination and liberation movement followed by the birth of Bangladesh as an independent country were based on the question of the right to mother language, and rightfully so. The language movement shaped the character of the liberation movement of Bangladesh by pushing the people to question their national identity beyond the question of religious and class segregations. It also shaped their thoughts and ideas on autonomy, self-determination, and freedom. In Purbo Banglar Bhasha Andolon o Totkaleen Rajneeti (The Language Movement of East Bengal and Contemporary Politics), historian and author Badruddin Umar reflects on these ideas, while explaining the historic, cultural and economic context of the language movement of 1952.

The book is divided into three parts and is based entirely on extensive research and interviews which chronologically document—and critically analyse—every political and cultural movement that followed from the partition of 1947 to the aftermath of the protests against the declaration of Urdu being the state language of Pakistan in 1952. This includes movements of revolt by farmers, workers, students protesting the privatisation of education in 1962, and the formation of a politically conscious population-base throughout these events. This eventually gave rise to a collective consciousness of discriminations based on ethnicity, until the consensus slowly shifted towards a move for autonomy, self-determination, and freedom.

When the Vice-Chancellor of Aligarh University, Dr Ziauddin Ahmed, supported the idea of Urdu being the state language of Pakistan inspired by the recommendation of making Hindi the state language of India, Dr Muhammad Shahidullah issued a statement of condemnation, in which he wrote, "If Urdu is recognised to be the only state language of Pakistan, following Congress's version of Hindi, it would only be a step backwards... The only case against English is that it is not the first language of any citizen living in any province of the Pakistan Dominion. The same goes for Urdu as well… It is not only unscientific and unethical but also goes against the practice of provincial autonomy and the right to self-determination."

While quoting such historic speeches in the early chapters, Badruddin Umar makes an interesting observation. The imposition of Urdu on the Bangla-speaking East Pakistanis was being justified from a religious point of view, since Urdu was closer to Arabic, the language in which the Holy Scripture of Muslims is written. This argument essentially excluded non-Muslim citizens, introducing a good Muslim-bad Muslim debate that was deliberately meant to segregate and marginalise religious minorities. In Dr Shahidullah's statement, he completely disregards this argument and refuses to discuss the issue from a religious lens, which caters to the non-communal spirit of the people of Bengal. This later became a key characteristic of the liberation movement of Bangladesh.

The formation of a national identity essentially requires a cultural identity. This cultural identity of the people of East Bengal was under attack by the oppressive Pakistani regime. It was never just about language, it was about crushing an entire cultural base. From the recommendation to write the Bangla alphabets in Arabic to putting a halt to everything that represented Bangali culture on record, such as poetry or traditional music, attacks came in all forms. But the people showed resilience. Cultural organisations like the Tamaddun Majlish played a key role in fighting for the cause of Bangla as official and state language of East Pakistan. These events were crucial in instilling the confidence among the people that injustice, anywhere, can be fought vigorously, no matter how powerful the establishment is.

In the course of this particular discussion, Badruddin Umar chronologically outlines an interesting trend. Student politics, in general, was widely expanded through the language movement. Umar's research shows the ascent of political-activist groups such as the Democratic Youth League, East Pakistan Youth League, and the Bangladesh Student Union, organisations which went on to popularise political activism among students and the youth, and nurture quality leadership. This confidence was reflected in and would prove to be vital for every movement that followed, including the war of liberation in 1971.

In his process of recounting this history, Umar highlights the presence and contribution of left-wing politics since the inception of the movement, for which left-wing politicians fell under the surveillance of the regime. This is a fact which has often been ignored in the retelling of the history of our liberation, sometimes even intentionally. It was Gono Azadi League, a left-leaning faction of the then Muslim League, who brought the issue of language into light back in July 1947, even before Pakistan became an independent state. This faction was focused on the economic freedom of the people and believed that attaining only political freedom from the British Raj would not do any good to the masses if poverty, economic injustice, and inequality were not eradicated from the society. They were the first ones to ask for the right to education through Bangla in the then East Pakistan and recommended that Bangla be made the state language of East Pakistan.

Reading this book makes you realise Badruddin Umar's dedication as a researcher and an author to fulfil his obligations to history by preserving it in the most accurate way possible and disseminating history to the masses. He chronologically describes all the major and minor events of the then political scenario of the country, all the while proving why the language movement is of utmost importance in the history of our independence—because it gave the people a chance to make their voices heard, and in the process prepared them for self-determination, paving the way for the birth of a new nation.

Read this article online on The Daily Star website and on fb.com/DailyStarBooks on Facebook, @thedailystarbooks on Instagram and @DailyStarBooks on Twitter.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is sub-editor of Toggle, The Daily Star and a contributor of Daily Star Books.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments