In ‘Pachinko’, a Record of Forgotten Lives

Even in the most extraordinary of political times, someone must tend to the crops. Someone must weave clothes for the winter. These everyday tasks fall not to the revolutionaries who earn our tributes but to ordinary folk persevering through wars and famines without recognition. History, says Min Jin Lee in the opening line of Pachinko, has failed them.

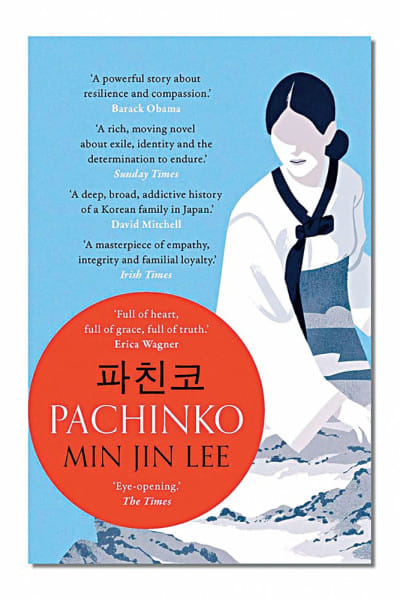

In a sprawling family saga spanning four generations from rural 1910s Korea during Japanese occupation to bullish Japan of the 1980s, Lee offers a corrective. The 20th century's most notable events are footnotes in Pachinko (Grand Central Publishing, 2017). The spotlight is on the people that history has forgotten.

The novel centers on Sunja, the hardworking and illiterate daughter of a Korean boarding-house owner. Just as the Japanese are tightening their grip on the Korean peninsula, two men arrive to disrupt her meagre existence. With yakuza-connections, Hansu brings starry-eyed glamour into Sunja's privations, leaving when she reveals she is with child.

Isak, a kindly pastor, then transports Sunja from the backwaters to Osaka as his wife, saving her from dishonour and making her the Baek family matriarch. In Japan, Isak's idealism and naiveté burrow the family deeper in poverty as they weather the major upheavals of the 20th century, including the atomic bombings of Japan, where at least 40,000 Koreans died.

Pachinko's ensemble of immigrant characters brings to light the plight of ethnic Koreans in Japan who migrated or were forcefully brought over between 1910 and 1950. Their descendants, known as the zainichi, continue to face discrimination and social isolation. "This place is only fit for pigs and Koreans," says Isak's older brother, Yoseb, when the couple arrives at the Osaka ghetto they will call home. For a Korean man, the choice is always shit, Yoseb thinks to himself in another moment of reckoning.

The immigrant's ache for dignity and belonging are captured in the family's second generation, Sunja's sons Noa and Mozasu. Each takes a different route through education, wealth, and denial of Korean heritage, only to find the deck stacked impossibly high. By the novel's end, the family has been in Japan for three generations. They are yet to be recognised as Japanese. Change, the novel concedes, takes time.

Written in the tradition of the 19th century novel, Pachinko is a triumph of interiority. Lee is deft with characterisation and elegant in introducing and exiting characters seemingly at will. Her roving omniscient narrator flits between men and women, the rich and the deprived, Japanese and Korean, making every scene intimate and revealing.

The book is not without its clichés. Hansu is somewhat of a contrivance, too, carrying the two halves of the story on his back. But Lee knows how to sharpen the edges of her narrative with an observation, context, or commanding interiority, making familiar moments meaningful. Her careful pacing helps tremendously, slowing down and picking up speed as needed.

This is Lee's second novel, published a decade after her first. In this time she lived in Japan, interviewing Korean-Japanese people there, and wrote multiple drafts for what became Pachinko. Her in-depth research shines through here, giving us an intimate view of the cultural dissonance of contemporary Japan.

For a Bangladeshi reader, Pachinko's key themes of belonging, racism, cultural erasure, and resilience against the odds resonate deeply. We have had our own tormented history with refugees in this country. With a million more joining in recent years, Pachinko offers a sobering glimpse into what the future might hold.

Shoaib Alam is a writer and chief of staff at Teach For Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments