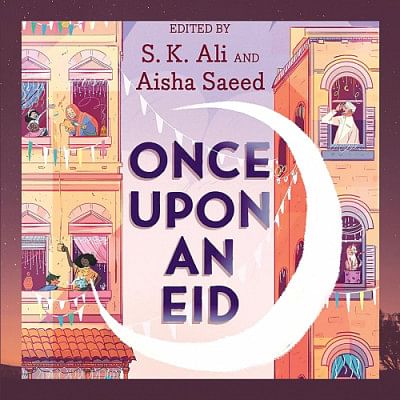

'Once Upon An Eid': A rare glimpse into Muslim homes

Diversity can seem jaded when it is employed for the sake of appearing "woke". But books such as Once Upon An Eid: Stories of Hope and Joy from 15 Muslim Voices (Amulet Books, 2020), written by individuals who simply want to rejoice in the intricacies of their culture, can be incredibly refreshing for readers who live both in and outside of that landscape. Equally refreshing is the depiction of Muslim practices unscorched by the accusations of being terrorists or "outsiders", even when the characters stretch from New York to Pakistan and all the way to refugee camps in Greece, all celebrating Eid-ul-Fitr and Eid-ul-Azha in their own way.

The short stories, poems, and graphic narratives in this anthology don't necessarily deny the complications of practicing Islam in an increasingly hostile world. In fact, most of the pieces focus on Muslim immigrants living in the West. Candice Montgomery's short story "Just Like Chest Armor" unpacks how an 11-year-old Spanish-Caribbean Muslim feels her way around the hijab for the first time—Leila relishes the softness of the fabric against her cheek and having her father brush her thick curls into the hijab every day before school. To her, the hijab represents freedom and the promise of dipping her toes in an adult world (like her Mama), as she watches her father turn the hijab into a cape around his own shoulders. Yet her mother wants to stay the process, wants her daughter to truly be prepared before wearing it "out of the house and in spaces that test who [they] are."

These lighter stories sketch out vibrant scenes of families celebrating Eid. While in "Perfect", Philadelphia resident Hawa chafes against her West-African Mandinka roots, in another story two cousins salvage burned Eid desserts with the help of elders. Two Pakistani siblings process their shock at seeing mountains of raw meat at their grandparents' home on Eid-ul-Azha and learn its historical significance in "The Feast of Sacrifice". The comic strips in "Seraj Captures the Moon" offer a break from all the text, and feature a young girl who sets off in search for the crescent moon with her donkey, away from distracting city lights, spurred on by the knowledge that "not all the things Allah asks from us are easy."

If these stories seem to skim the surface with their upbeat tone and plot, that's because it's mostly meant for a young adult audience. In the more complex stories, though, the language gathers depth. N H Senzai's "Searching for Blue" walks us alongside young Bassem, who lost his father to the Syrian civil war. Bassem is a subdued narrator; war has robbed him of the childlike excitement driving the other young characters in the anthology. In reflection of his hard-earned wisdom, the prose here offers subtler but thornier observations by juxtaposing fancy tourist life against the refugees also stranded on the Greek shore: "Solemn and peaceful, the Church of Mary rose at the corner beside a restaurant. The Apollo Hotel came next, a bright pink concoction resembling a fluffy birthday cake. A boy stood at the gates, sweeping the steps."

Elsewhere, Hannah Alkaf's poem "Taste" uses vivid, haunted descriptions of Indonesian cooking to depict a child's trauma of losing a parent. "Candlenuts, round and hard; lemongrass, but only the white bits;/ shrimp paste, toasted so that the smell fills the entire/ house and makes Aiman cough (Stop it , kakak!). […] I run a finger over the knuckles of my right hand, smiling at/ the ghost of a hard rap from a wooden spoon/ and mama's voice, half laugh, half scold: The taste is different, Alia!"

In "Eid Pictures", Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow's verse inspires nostalgia and solidarity with Muslims through the ages, tracing as far back as when being coloured meant slavery. "…bright garments making music as they glide against dark skin. […] The Eid pictures in my family's old photo albums, though—/ they calm,/ settle/ and soothe me like Jeddah's arms. […] Picture Eid for the first Muslims who came to American shores […] Close your eyes and picture them/ in ships,/ in chains, / enslaved."

For most of my life, cosy holiday reads in English have inadvertently involved reading about Western traditions—twinkling Christmas lights, presents under a tree, the warmth of pudding and turkey while the world outside lay blanketed under snow. Beautiful as they are, these tropes have never resonated with my own holiday experiences as a Muslim Bangladeshi woman. Once Upon An Eid would have been far richer—and dearer—had it also portrayed Eid celebrations in Bangladeshi homes. Nonetheless it offered the unique thrill of finding myself, my history and rituals, in the pages of a book, that too somewhat unfiltered from a White and Western gaze. On this Eid, which hardly feels like one given the ongoing pandemic, this is the kind of comfort we could use.

Sarah Anjum Bari is head of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or

@wordsinteal on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments