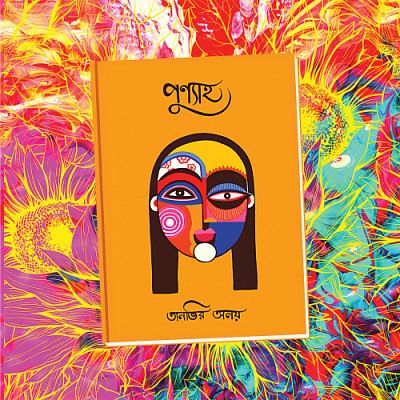

Relationships lost and found in debut novel ‘Punyaha’.

In the middle of nowhere, among the wide expanse of paddy fields stands a wee nursery—an oasis of sorts, a respite from the outside world. There, long lost duo Farzana and Shamita have finally rekindled their relationship, yet their various entanglements painfully keep them apart and away from their sanctuary. On the one hand, there is Farzana's entitled husband, Mahfuz, who wants to exploit what it means to be in a marriage. On the other, Shamita's greedy brothers emerge as land-grabbers who attempt to take away what is rightfully hers. Both Farzana and Shamita are ordinary women, their struggles, too, are distinctly Bangladeshi. Many a woman in literature or film is plagued by the tyrannical husband, greedy brothers, a wayward child, or the return of an old lover. Why then is Tanveer Anoy's Punyaha (Boobook, 2021) creating so many ripples that have turned into rather turbulent waves?

The novel is Tanveer Anoy's first of many to come. The author is a prominent, young activist and prolific writer who is vocal about, among other issues, gender discrimination. The two leading ladies of his novel are hence immaculately crafted characters who speak, think, and decide for themselves. It would not be surprising if the world revolved around men in a novel set in a patriarchal society, as does real life. Even so, Farzana and Shamita have other things to talk about, such as books and how to care for the many plants at the nursery. Shamita, whose comfort zone lies in Bangla books, jokes about Farzana's privilege to be able to read her "Austin-faustin" in English. This novel not only passes the Bechdel test, it also subtly hints at the two friends' class differences.

Punyaha raises quite a few poignant questions in the face of current social structures. Even today, it is bold for any work of fiction to begin with a failed marriage. We meet Farzana at a point where she is done making sacrifices, and Mahfuz's true self has already materialised long before the events of the book. Prachi, Farzana's stepdaughter, returns home but has long crossed the threshold of no-return. What used to be a dream home for a family is now under the surgeon's knife, about to be dissected into pieces in the name of rightful inheritance. For a single, Hindu woman like Shamita, inheritance is even more of a crouching tiger that threatens to take away her autonomy and fortitude. Like quicksand, old values are shifting from under their feet. Like tangled webs, these same old values complicate their dreams in the name of tradition and social order. What, then, is the meaning of family or home for these characters? The reader is distraught in a myriad of relationships, searching for a semblance of warmth where there is none. Such is the gaping hole that the novel digs for us from the very start.

One might face a little trouble understanding stepdaughter Prachi's exact purpose in the story, as to what she helps the reader come to terms with, as a character. The language itself might sometimes appear disjointed, flowing somewhat tensely in places. A peppering of words such as "tobda" or expressions such as "biggoban manush'' may read somewhat curiously. But the questions raised, again, are bold and reveal many aspects of society—the rise of a new brand of religious conservatism, eroding social structures, and queer identities struggling to find a voice in the midst of it all.

The word "punyaha" refers to a celebration, a cleansing ceremony to purge the earth. At the same time, "punyaha" was a festival associated with the collection of taxes. One might ask, to whom was "punyaha" a festival, if at all? Who did, in fact, celebrate a day of prejudicial taxation and mercilessness of the zamindars under the British Raj? Tanveer Anoy's novel Punyaha does not come to the ordinary person as a bearer of good fortune, nor does it balance their books. It perceives the anomalies of society with a queer lens and keeps it at that.

Qazi Mustabeen Noor is a lecturer at the Department of English and Humanities, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments