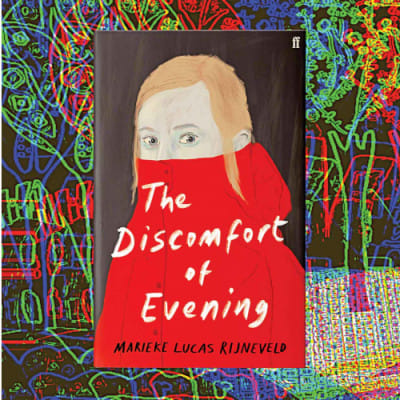

Repulsive, But For A Reason

The mind of ten-year-old Jas—the narrator of Marieke Lucas Rijneveld's 2020 International Booker Prize-winning The Discomfort of Evening (Faber Books, 2018)—is a canvas with one enduring quality: the whimsical innocence of a child. And when brushstrokes of a variety of unpleasant experiences drift across it, the reader is left with an image that is dark and at the same time poetic, humorous, and peculiar. Consider these: Imaginary Jewish people hiding from a 20th century war in a 21st century basement. The froth of milk forming a Hitler-like moustache bordering the lips of Jas's father. Jas fearing that her parents might die and holding a tooth fairy captive to wish for new parents. "A mass grave of milk biscuits". And a dead rabbit's teeth growing from the earth, which could possibly puncture Jas's father's torso.

Jas's brother, Matthies, is dead. After losing him in an ice-skating accident, a gloom rolls over their lives, enveloping the farm in which they live in a thick film of grief and longing. His absence is everywhere: "In the middle of the mattress, there's the hollow of my brother's body…a hollow that I try not to end up in." But Jas is also desperate for a Discman, even though she suppresses the urge to ask her parents for one. After all, her "parents' loss is much worse—you can't save up for a new son."

This is what the book is essentially about—the disintegration of a conservative family in the wake of a tragedy.

Jas has two other siblings: Obbe, who tortures butterflies and animals by suffocating them, and Hanna, who thinks Jas' nails are turning black because she's pondering about death too much. Obbe is that bullish sibling who will use the dirt on someone else to resort to unthinkable ways of punishment. Hanna is supportive, easily led to saying yes to every scheme, be it performing a ritual to ward off death or giving into incestuous intimacy. In the presence of few characters, the exploration of the relationship shared by these siblings is what drives the narrative forward. It results in philosophical insights and adds conflict and thrill to the story.

Before reading this novel, I did not know that the "unrolled wall" of one's small intestine can sprawl over the length of a tennis court, that ants can carry 5,000 times their own weight, and that an earthworm has nine hearts. Strange bits of information such as these are peppered throughout the story, but they serve the additional purpose of revealing the inner workings of a child's mind, whose whimsy is often a means to processing the dark and grand mechanisms of life on earth. For example, the weight carrying capacity of ants allows Jas to think of how humans so often buckle under the weight of their emotions. Aside from being a shrewd observer, in many ways, Jas is also a rebel. She lives in a religious household, but doesn't want to go to God, only to herself. She wants to be invisible and disassociate herself from the realm of humans.

The characters in the novel are at times obsessed with their own and others' bodies. This can feel discomfiting. It is the poetry and fluidity of the writing that make reading through the vividly unpleasant bits bearable. Even then, the portrayal of the discomforting offers a glimpse into human nature when it is stripped of normalcy, revealing the lust and violence beneath.

Originally Dutch, this novel was translated into English by Michele Hutchison. But a reader cannot find any uneasy, confusing, or incomprehensible crack in the language that can reveal a failure of translation. Perhaps, that is the beauty of perfect translation—besides the blurb on the cover, there's no way of knowing that the book was not originally written in English.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments