Revisiting the only book written by an Indian about the Indian soldiers of WWI

Tens of thousands of men sailed across the ocean to a land they'd never before heard the name of. They fought long and hard, in the world's first industrial war, facing airplanes and flamethrowers though few of them had even seen electricity before. They did this for an empire that oppressed them. They were cold. They wanted to go home to their children. They thought the world was ending. And though they were praised for their courage all the while, they were also kept under strict supervision by a government deeply suspicious of them. Those that survived to return were demonised and forgotten—they had served the masters, for nothing.

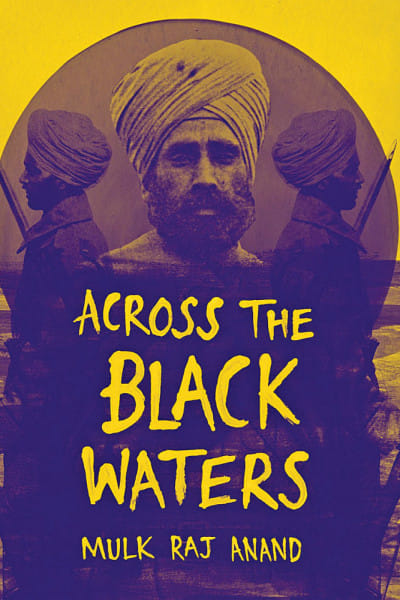

It's a good story, but only one person bothered to tell it. Mulk Raj Anand's Across the Black Waters (1939) is the only South Asian novel written in English that details the experiences of non-white soldiers in World War I. It is the only novel by an Indian about the Indian army fighting Europe.

Between 1914 and 1918, the United Kingdom deployed 85,000 Indian soldiers to the Western Front. It is well known that when the war broke out, Britain was unprepared and threw in its small army of professional volunteers into a conflict characterised by the millions-strong conscript armies of the Continent. It is remarkable that they held the line against the Germans, but their success would have been impossible without Indian bodies to plug the gaps.

There exists a large body of largely dictated letters written by these Indian soldiers from the front. They were frequently eloquent, even poetic. They exist now only in censor reports at the British Library, and for the duration of the war the Indian soldiers' words were inaccessible to a global audience. Unable to speak, he was spoken for, with a number of British authors such as Rudyard Kipling writing stories from the perspective of the soldier. This literature tends towards propaganda, using the assumed voice of the Indian to reassure the British public and its allies that these soldiers had no desire, or mental capacity, to be anything but simple servants of empire. It was a genre constructed from Orientalist fantasies, telling us much about what anxieties kept the British up at night, but telling us nothing about the world of the Indian sepoy.

If you read any of this literature—Kipling's The Eyes of Asia (1916) or Talbot Mundy's Hira Singh (1918), as examples—and then stumble onto Anand's book, it's like a jolt of lightning.

Anand was a fierce antifascist who straddled the worlds of British literary intelligentsia and Indian revolutionary nationalists. He drafted Across the Black Waters while fighting Franco in the Spanish Civil War. The story is simple: the narrator, Lalu, a cynical young man, navigates the war in France alongside his friends, encountering Europe in its beauties, hypocrisies and horrors, and then returns home, changed. It is the novel you would expect it to be, and that is what makes it unique. In the constraints of British imperial literature, Indian soldiers were never allowed the space to breathe and just be—they only existed as sock-puppets of propaganda.

Anand treats his characters (each distinct, sharply characterised) with respect. We see them not only in relation to one another but also how they navigate their experiences with a whiteness they had been taught to fear and respect. The wonders of Europe reinforce their awe; the horrors of war and the incompetence of British high command (what could be a more classic theme of a World War I novel, white or brown?) break their respect for the British. They kill Germans, see Tommies soil themselves in fear, and play with French children and bed French women. The binaries of white-and-brown are moved beyond: the soldiers find their white, British officers kinder than the Indian officers, who are shown to be keen to bully their fellows; and they are awed when they learn about Joan of Arc, admiring the young French girl who defeated the mighty English, long ago. It is rich in fascinating moments of cultural encounter, infused with an anticolonial spirit that never sacrifices nuance for the sake of making a partisan point.

In fact, the only reason to avoid the novel may be the rather colourful village vernacular the characters talk in, laden with proverbs and friendly, hair-curling expletives. Irritating as this can be, there is a charm to it. The characters talk in a way that shows their lives are lived-in, that they know each other well. It is remarkable that much of the novel is taken up by scenes of the everyday: making fun of friends, throwing snowballs, doing the washing, and playing with children. It is even more remarkable that no one else bothered to write Indian soldiers in this way.

Across the Black Waters had been forgotten, in India and beyond, for the most part. It is now seeing a resurgence, especially in academia, as interest in World War I is at an all-time high following the 100th anniversary of the Armistice in 2018. Anand's death anniversary of the 28th of September reminds us to revisit his work, in honour of men whose words were lost but imitated in Across the Black Waters with a rare respect.

Zoheb Mashiur is an Early-Stage Researcher at Charles University, Prague. He is writing his doctoral thesis on literary representations of Indian soldiers in World War I.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments