‘Saogat’ magazine and the gift of critical thought

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Bengal was rife with the struggle for identity and socio-political upheaval, particularly in the Bengali Muslim communities. The tensions inspired magazines and periodicals devoted to intellectual thinking—in the months between April and June of 1819, the monthly Digadarshan, the weekly Shamachardarpan and Bengal Gazette, and the quarterly Bangiyo Musalman Shahittya Patrika were first published, all written in Bangla. It was against this backdrop that Saogat came out on December 2, 1819, conceived by the visionary journalist and editor, Mohammad Nasiruddin.

From Chandpur to Kolkata: An Origin Story

Nasiruddin began working from a young age—first as a betel nut trader, then as a ticket collector at a rail station, and finally as an insurance officer. Yet his heart remained in the realm of literature. He nursed an urge to act against society's prejudices and ignorance, and knew that publishing a newspaper from within the Muslim society would help create a breathing space for progressive discourse. In 1917, he left Chandpur for Kolkata to turn this vision into reality.

But the Muslim individuals to whom he proposed his idea balked at the prospect. None were keen on bringing out a publication that would contain art and fiction like the magazines printed by Hindus. Nasiruddin persevered, travelling back and forth between Chandpur and Kolkata, until finally he came across barrister Abdul Rasul, who became a stalwart supporter.

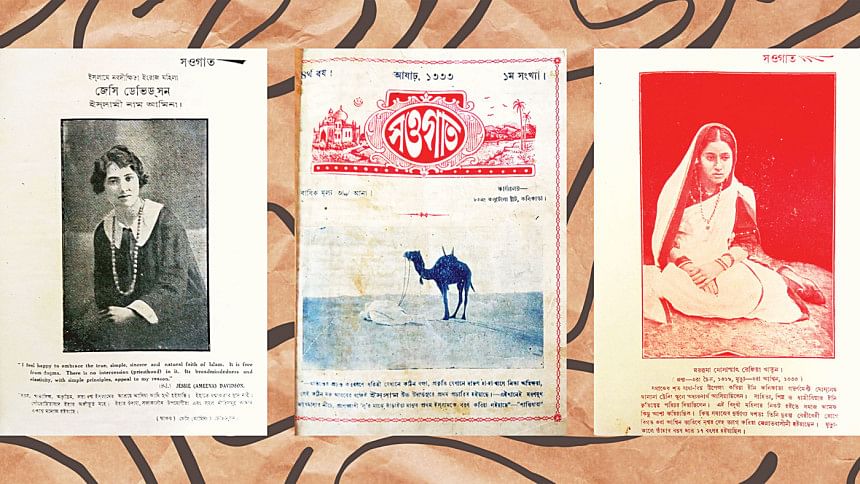

The first November-December issue of Saogat, an illustrated literary magazine, came out in the Bengali year of 1325 in Kolkata, and as its editor, publisher, and founder, Mohammad Nasiruddin changed the nature of intellectual discourse in Bengal. The first issue contained pieces by Jaldhar Sen, Brajendranath Bandyopadhyay, Satyendranath Datta, and Mankumari Basu. Begum Rokeya wrote her poem "Saogat" under the pseudonym of RS Hossain.

Through Saogat, Nasiruddin advocated for the education of Muslim, Hindu, Brahmin, and Christian girls and women, who had long suffered under patriarchal social codes. The magazine would become a pioneer in publishing images of Muslim women on print—an unthinkable act at the time. Soon, writers like Kazi Nazrul Islam, Begum Rokeya, Abul Mansur Ahmad, Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Sufia Kamal, and many others were engaged in this project of generating liberal discussion and dissent in the Bengali Muslim community. Beyond just a print platform, Saogat became a stage for the cultivation of the arts, and a space where new and veteran writers gathered for the quintessential Bengali knack for adda.

The Dhaka Chapter

1947. An atmosphere of chaos and strife. Bengal was now divided, and religious fanaticism triumphantly rode the air. Hailing from East Bengal, Nasiruddin found it strenuous to continue working in Kolkata in such an environment. In 1950, he returned to Patuakhali.

Two years later, in the middle of 1952, Dhaka was pulsating with the spirit of the language movement. Saogat had become defunct by then. When a group of young writers led by Hasan Hafizur Rahman met up with Nasiruddin, insisting that the magazine could pave the way for critical thinking in Dhaka in the way that it had in Kolkata, the journalist found himself, once again, inspired. Saogat's first issue in Dhaka came out in November-December of 1953. Unfortunately, it failed to recreate the impact seen in Kolkata, and paled against the popularity of Nasiruddin's second brainchild, the Begum magazine.

A Force against the Current

By virtue of its stance on freedom of thought and speech, Saogat consistently attracted criticism from the conservative factions of society. Nasiruddin was branded anti-Islamic and a Kafir, among other labels. But the editor refused to relent. In Showgat O Amar Jibonkotha (Protichinta publishers), he wrote, "My personal life doesn't hold anything remarkable. Whatever I have accomplished, everything is indebted to Saogat. I was born in a very ordinary household. I published Saogat by the sheer strength of my own perseverance and character."

Between 1793 and 1828, a law relating to non-taxable property was enacted, which spelt losses for both Hindus and Muslims. One of the reasons as to why the Muslims lagged behind was their distaste towards the English language, which replaced Persian not long after in 1835. Muslims abhorred the British rule and as a result, unlike the Hindus, were unable to secure better government jobs.

Many individuals and organisations worked tirelessly to fight this status-quo. Platforms like the Bongiyo Muslim Shahitto Potrika (Muslim Bengali Literary Paper), the Muslim Literary Society of 1926, and the Bengali Muslim Renaissance Society of 1942 played significant roles. Organisations like Saogat and Shikha heralded readers towards progress amidst the tug of war between Bengali Muslim nationalism and Brahminism, which was strangling people's freedom of thought. For sowing the seeds of such pioneering thought and practice, Saogat and its like have left us with an enduring debt.

Emran Mahfuz is a poet, writer, and researcher. Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments