Sweet, Sour, and Savoury: A Post-Partition Tale

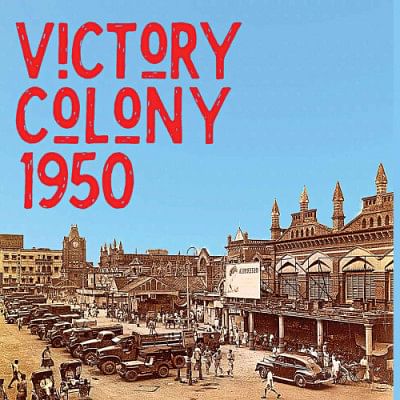

There are few pleasures in the life of a Bangali that come close to the sheer delight of basking in the rare but sweet Sun on a winter morning on the balcony, accompanied by the aroma of a cup of tea, sweetened with milk and sugar, while you immerse yourself in a book that won't spoil the harmony of this experience. Bhaswati Ghosh's debut novel Victory Colony, 1950 (Yoda Press, 2020) fills this role quite well.

Amala is a young refugee whose parents were the victims of communal riots in East Pakistan after the Partition. She also loses her only brother soon after arriving in Kolkata. When Amala is being escorted to one of the refugee camps, we meet Manas, a sensible young man from an educated, upper class Kolkata family.

The strength that imbues Amala gives the novel its heart. She is the symbol of the refugees' endurance in the face of constant struggle for survival. Manas's perspective on the influx of refugees to his city sounds like the voice of conscience. If Amala represents the refugees from the East, Manas can be read as the bright side of Kolkata which has opened its doors to welcome the stranded.

Manas's attraction for Amala is easily felt from the beginning of the novel and the progression of their relationship does not come as much of a surprise. Through their bond, the novel aims to symbolise the harmonious existence of the refugees and their culture in Kolkata.

As an instrument of storytelling, the novel is delightful in its reliance on Bangalis' love for food, which has not been done before. From Chitra Mashi's macher jhol and fried fritters to the moments when Amala and Manas share a pack of muri-makha in the refugee camp, it effortlessly penetrates the personal and cultural spaces with food.

In fact, reading Victory Colony, 1950 at times feels like a trip to my maternal aunt's place. The probability that the trip will end badly is slim to none, it is filled to the brim with affection and warmth, and not an hour goes by when my palate is not treated with a delicacy. (I hope my mother doesn't read this, or she will certainly yell—keno, toke ami khete dei na? One of the great things about this novel is that it has no shortage of doting mashis.

While the book spends considerable time in detailing Manas's aristocratic home, however, it dwells surprisingly little on the existential crisis of the refugees. Nor does it aim to portray a complete picture of how the people of Kolkata responded to this huge influx to their city. We see Manas's enthusiasm in helping the refugees but he is a college educated member of an aristocratic family. The confrontation of the local zamindar with the residents of the Bijoy Nagar (Victory Colony) cannot be taken as representative of the response by the general people of Kolkata across classes and communities.

Over the recent years, we have seen Donald Trump and his supporters' reaction to Mexican immigrants pouring in from America's southern border. In our own backyard, we have been reluctant to share our resources with Rohingya refugees who have narrowly fled the grasp of death. Unlike Manas and his group of volunteers, the incessant buzz here is—when will they go away?

As an antidote, Victory Colony, 1950 makes a case for finding hope and resilience when life throws its harshest weather at you—the cold and foggy early hours of the morning making way for the glimmering, warm rays of the Sun.

Mursalin Mosaddeque grew up in the suburban town of Rangpur in Northern Bengal.Instagram: @bluets001

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments