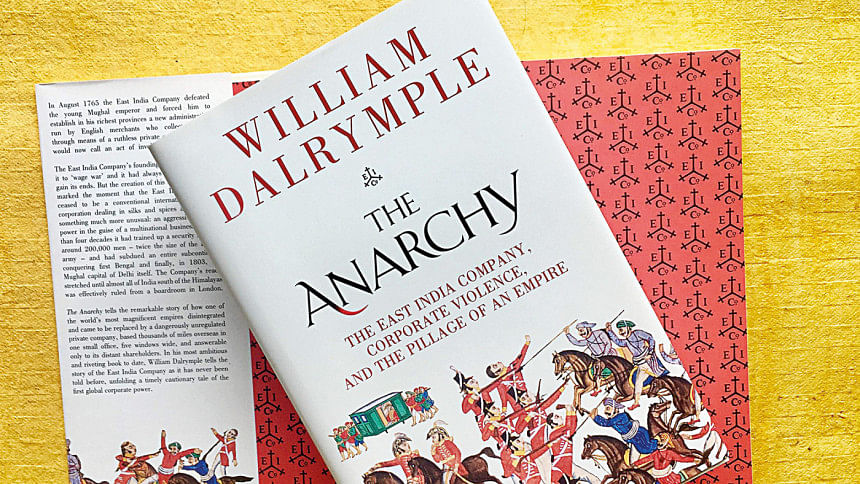

The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire

Here is a door stopper for the lingering period of hibernation. All 522 pages provide ample literary support for long-term homebound inmates. The alternative and or follow-up literary immersion is "The Presidential Memoirs," Barack Obama's "Promised Land." He offers the tenacious reader 768 pages in Volume 1 alone. Wordsmiths of two different genres; yet both write with the stature of an artist. The Anarchy was listed by Obama as one of his Top Ten Recommended Books of 2019. "In Praise for William Dalrymple," Maya Jasanoff, historian at Harvard University declares: "Dalrymple researches like a historian, thinks like an anthropologist and writes like a novelist." An unstoppable researcher, a master storyteller and the most ambitious of his prolific literary repertoire, The Anarchy was six years in the making.

Meticulously researched, The Anarchy presents a compelling canvas to a vast landscape in vacuum. Political cracks created cleavages and chasms across the Indian peninsula as early as during Emperor Aurangzeb's reign of close to half a century (1658-1707). Although it was under Aurangzeb's reign that the Mughal Empire reached its greatest extent. Yet its dissolution was helped by his divisive and war mongering policies.

Divided loyalties if not desertion and short-term affiliations if not assignments for short-term gains; corrosively undermined and eclipsed decaying imperial influence. Add to it hereditary feuds; where intimidation, deceit, deception, murder and usurpation within the ranks of rajahs and rulers and masters and maharajahs was widespread. Trading agents became merchant princes. Influence seekers, mercenaries and loan sharks omnipresent. Widespread political manipulation by collaborators and turncoats; securing allies serendipitously persisted in a vacuum of stability and security. And you have a landscape ready for the taking; open for appropriation and exploitation. Other foreign trading agents on the lookout for economic conquest; namely the Portuguese, Dutch and French were outsmarted by EIC money and men.

The year 1739 was both ominous and devastating for the Mughal Empire. Nader Shah, the Persian ruler invaded India. According to Dalrymple, "Nader never wished to rule India, just to plunder it for resources to fight his real enemies, the Russians and the Ottomans;" an economic conquest which he accomplished most successfully. "Fifty–seven days later, he returned to Persia carrying the pick of the treasures the Mughal Empire had amassed over its 200 years of sovereignty and conquest; a caravan of riches that included Jahangir's magnificent Peacock Throne, embedded in which was both the Koh-i-Noor diamond and the great Timur ruby…700 elephants, 4,000 camels and 12,000 horses carrying wagons all laden with gold, silver and precious stones, worth in total an estimated Pounds Sterling 87.5 million in the currency of the time." That wealth looted and loaded is most conveniently noted for the reader as *Around Pound Sterling 9,200 million today* in a footnote. To add pounds of salt to India's deep wound, we are told "As the EIC Writer William Bolts later noted, seeing a handful of Persians take Delhi with such ease spurred the Europeans' dreams of conquests and Empire in India. Nader Shah had shown the way."

Who would have envisaged that a far distant Anglo-French rivalry constant on the European continent, then transferred to America would also transfer itself across oceans to the Indian Subcontinent? A seventeen year old British lad boarded a ship for Calcutta in December 1742 to take up the most junior rank of 'Writer' working as an accountant. Robert Clive was his name. A masterful summary of the young man's character is put forth by Dalrymple. "What he did have, from the beginning, was a streetfighter's eye for sizing up an opponent, a talent at seizing the opportunities presented by happenchance, a willingness to take great risks and a breathtaking audacity." These features took him far. In 1752, he defeated a French attack on Madras. A thirty-year old Robert Clive was signed up by the EIC for a second time in 1755. This time the appointment was Deputy Governor of Madras with a military rank in the army. "…the directors were keen to send Clive back to India at the head of the private army of sepoys that Clive himself had helped recruit, drill and lead into battle." His directive was to ward off any further French threat to Anglo expansion in its scramble for India. This was "An Offer He Could Not Refuse" as the chapter is precisely headed.

We are told that "Bengal had always produced the biggest and most easily collected revenue surplus in the Mughal Empire." Marwari financiers originally from Jodhpur provided credit networks for the annual tribute to Delhi. "…the Emperor had awarded the title the Jagat Seths, the Bankers of the World, as a hereditary distinction…the Jagat Seths exercised influence and power that were second only to the governor himself, and they soon came to achieve a reputation akin to that of the Rothschild in nineteenth century Europe" declares the author. These financiers evolved into political decision-makers. At the definitive battle of Plassey in 1757, "Clive "transferred to the EIC treasury no less than Pound Sterling 2.5 million (*262.5 million today*) seized from the defeated rulers of Bengal." It was the beginning of "the slow drift to the Company of troopers, merchants, bankers and civil servants, leaving the Nawabs with nothing more than the shadow of their former grandeur."

In a long drawn out power-play between the reigning Mughal Emperor and the challenging forces of the Rohillas, a young rebel Rohilla chieftain, Ghulam Qadir Khan was captured in 1772 by Shah Alam II in battle. Dalrymple elaborates: "and taken back to Delhi where he was brought up as an imperial prince. Some sources indicate that he was a favurite of Shah Alam and may even have become his catamite." I had to look up "catamite" - "a boy kept for homosexual practices, the passive partner in sodomy." In a reversal of fortune and surely in an act of revenge, the Mughal monarch was defeated, tortured and blinded in 1787 by Ghulam Qadir Khan. Shah Alam II continued on the gilt replica of the Peacock Throne in Delhi till his demise in 1806 – a figurehead of convenience for all.

A principal challenger to the EIC expansion in India was the might of the Maratha Confederacy. Peshwa court administrators and armies preempted the British at every turn of their game; while corresponding internecine intrigue within the Maratha Confederacy undermined unity. Three Anglo-Maratha Wars took place between the years 1775 and 1817. Dalrymple writes: Cooper, 'The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns' contains much the best account of the battle. I visited the site of the battle with the current Duke of Wellington and found Cooper's maps invaluable. A single East India Company lead musket ball that I picked up at Pipalgaon while walking the battleground sits in front of me as I write." The author's loot to boot!

Richard Wellesley at the age of thirty-seven arrived in Calcutta in May 1798. He was to take up his appointment as Governor General of the Company's possessions in India. "He was determined to secure India for British rule and was equally determined to oust the French from their last footholds on the subcontinent." He was to negate the presence of "sepoy armies trained by French mercenaries and renegades, and all of which could, potentially, be used against the British and in favour of the French." His goal to defeat the Nizam of Hyderabad was achieved in October 1798.

At the fierce battle of Srirangapatnam in 1799, the "Tiger of Mysore" Tipu Sultan's forces were wiped out by the East India Company's (EIC) army, the "Tiger of Mysore" was killed and in a victorious motion; we are told: "Ladies and gentleman," said Lord Wellesley, raising a glass, when the news of Tipu's death was brought to him, "I drink to the corpse of India." Here is an expansive and gripping narrative of the military tactics and political machinations of the EIC. Thoroughly engaging, the details of the battle and the bounteous booty make for a most engaging account of a singular military encounter.

The closing chapter with its tragic heading "The Corpse of India" is a consummate climax to The Anarchy. A pensive read is the decline and fall of the mighty Mughals. A dramatic read is the relentless rise of a tiny office five windows wide in London, whose 218 investors received a royal charter in 1600 and founded a small enterprise – namely the East India Company. Weighty is the following sentence in Dalrymple's first chapter "1599": "It is always a mistake to read history backwards." That small trading office persistent with grit and greed evolved into the world's mightiest multinational corporation. The EIC laid the stepping stones for the transformation of the Company into the Crown - the British Raj; "The Jewel of the Crown." This is William Dalrymple's stellar, entertainingly nuanced bestseller of that long trail. 'The Anarchy' was one of three books shortlisted for the prestigious 2020 Cundhill History Prize offered by the McGill University, Montreal. The page-turner epic book is to be adapted to a television series by the Indian TV producer Siddharth Roy Kapur for a global audience.

Raana Haider is the author of India: Beyond the Taj and the Raj, published by UPL, Dhaka, 2013.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments