The Fall of A Great America

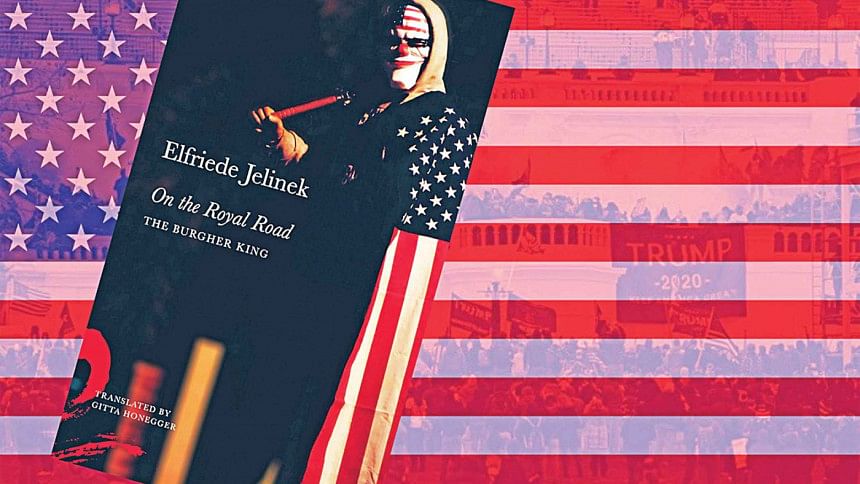

In a near-perfect echo of today's world, Nobel Prize-winning Elfriede Jelinek's On the Royal Road: The Bergher King (Seagull Books, 2020) is stuffed breathless with metaphors, innuendoes, and anecdotes as it satirises US President Donald Trump.

The foremost of these lies hidden in the title itself—the play follows the journey of an unnamed land after its petulant and destructive new "King" has just been voted into power; but the "Bergher" in the subtitle refers both to the German word, bürger, for "citizens", and to the US President infamous for his plump, garish, golden-orange aesthetic. Such is the nature of Jelinek's humour, translated from the German by Gitta Honegger. The things they write of are funny because they critique the obvious and the discomforting—the fact that the people "cast their vote, but don't know who they voted for, even though they did it themselves," for instance.

Jelinek finished writing the script three weeks after Trump was elected President on November 8, 2016. By the time Honegger began writing her Introduction to the English translation in September 2019, wheels were turning on Trump's impeachment inquiry. The text, therefore, evolved almost at par with the pace of life under Trump's rule, which, as the play recounts, has included everything from word vomit on Twitter to tax fraud, displays of aggression, sexual predation, denial of truth, and individuals being stripped of finances, citizenship, and human dignity. In one of the most relatable instances, Jelinek writes, "Everyone has his own facts and everyone else also has his facts, but different ones. Of course, they are not the same, but both are true. Thus everybody has a weapon against everybody." At the centre of this storm brewed by misinformation stands the golf-loving, gold-loving King, who insists, "Only i tell the truth, i alone, i have been legitimized, here is my king's id which has been forged for a long time, but now no longer, now it's the real thing."

To control all this chaos, Jelinek presents the play entirely in the form of a monologue, delivered by a blind seer in the Bergher King's court. This seer is a manifestation of Tiresias of Oedipus Rex, who foretold Oedipus' destiny. Here, though, the seer-narrator is a woman—that creature that both Trump and his predecessors of classic literature so loved to silence, and she is also Ms Piggy of The Muppet Show—as fitting a soothsayer for a cartoonish King as can be.

Seasoned readers will notice how the play engages with Greek myths and the philosophies of Heidegger and Girard to reveal the ironies and failures of our modern existence, buoyed and weighed down by capitalism, neighbourly competition, and the violence it all brews. For many, however, the rambling sentences and absence of a plot and chapters can be difficult to digest. But if one can find the time, each and every word by Jelinek can be examined to reveal harrowing truths about a world endangered by voice given to the blind, i.e. the world of January 6, 2021, when hundreds of Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol to challenge a free and fair election after being incited by his speech.

Jelinek's play was published before the breach of the Capitol, but in a fitting warning against the power of hate speech, it begins with a reminder that, "In the Beginning Was the Word", that "[e]verything has happened already, but isn't over yet." In the pages that follow, the play reveals unflinchingly how complicit everyone has been in the entire spectacle of the Trump presidency. And because Jelinek never actually names the country nor the leader, it becomes a raw and scary tale of power left unchecked which can apply anywhere in the world.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or

@wordsinteal on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments