Into the nuances of history: Sudeep Chakravarti unpacks the Battle of Plassey

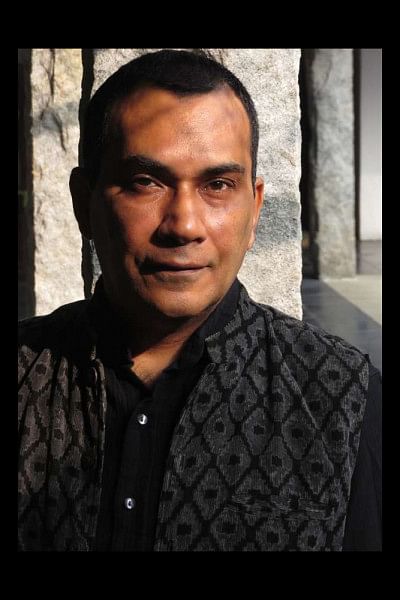

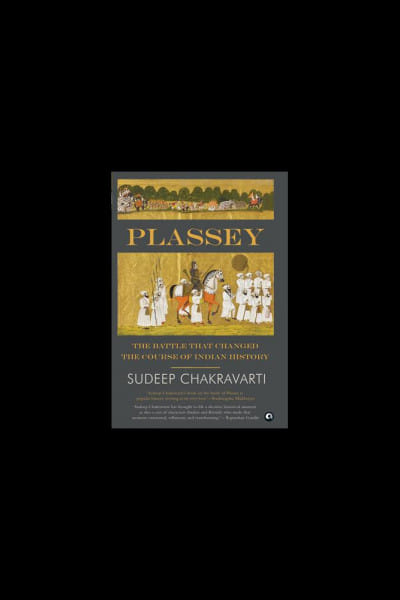

Sudeep Chakravarti is an eminent commentator and author whose narrative non-fiction and fiction have been translated into Bangla, Hindi, Spanish, Portuguese, German and more. In January 2020, his book—Plassey: The Battle That Changed the Course of Indian History (Aleph Book Company, India)—sought to parse through the history and the myths surrounding the topic. This week we brought together the author and our Commercial Supplements Editor Shamsuddoza Sajen to discuss the book and the battle, fought 263 years ago on June 23.

Shamsuddoza Sajen (TDS): Why did the British want to capture the throne of Bengal? Was the Battle of Plassey inevitable?

Sudeep Chakravarti: Bengal was a major Asian trade hub. Here cottons and silks were legendary, there was jute, lac, saltpetre for making gunpowder and preserving foods. Finance was relatively easy. The rivers and waterways ensured excellent transportation and communication networks. And Bengal was rich: its revenues helped to sustain Mughal coffers and armies. Even with the disintegration of the Mughal Empire, both French and British Company sources verify as to how Bengal sustained their Indian trade. The

British East India Company couldn't afford to lose Bengal, and they couldn't afford French

ascendancy in Bengal and India either. Siraj and the French were both perceived as great threats. The British wanted both to be removed from the chessboard.

A make-or-break conflict with Siraj-ud-daulah became a priority for John Company in early 1757. Robert Clive and Charles Watson had already helped recover Calcutta from Siraj's forces in January. Meanwhile, the Seven Years' War was breaking out in Europe, in which Britain and France were the main combatants. That hostility carried over to Bengal, and weakened the so-called 'Neutrality of the Ganges', a tenuous understanding by which Europeans attempted to insulate the Bengal trade. When Siraj's outreach to the French began to increase from February, the die was cast.

First the French settlement of Chandannagar north of Calcutta was attacked and destroyed by the British in March 1757. The elites of Murshidabad who had meanwhile been conspiring against Siraj now formally conspired with John Company against the nawab. The stage was set for what came to be called the Battle of Plassey, fought on June 23, 1757. But the outcome of the battle was far from certain. Indeed, despite his bravado Clive was a nervous wreck, and Company officials in Calcutta were fully prepared to dump Clive if the gambit went wrong—and Clive knew it! It's all in my book.

TDS: How did the Battle change the course of Indian and global history?

SC: There is absolutely no doubt about its far-reaching impacts. As an outcome of the battle the British defeated the French, their main European competitors, and put their imprimatur on the court of Bengal. And Plassey set off another chain of events: the deposing of first Mir Jafar, a key Plassey conspirator and then Mir Qasim, his son-in-law, as nawabs of Bengal. The Battle of Buxar in 1764 in which Company forces defeated Mir Qasim and the Mughal emperor. The granting of diwani of Bengal and Bihar to the British Company in 1765 by the Mughal emperor was a direct consequence. It gave the Company revenue and administrative control of Bengal—and helped raise and maintain armies alongside reversing the flow of bullion from Britain. This joint heft of money and power underwrote the Company's move west to Awadh, and then, in a few short decades, to Delhi. The Mutiny in 1857. The formal replacing of Company with Crown. Bengal—and India—becoming the hub and glory of the British Empire, underwriting its local and global growth and several local and global wars. It all began with the Company's victory—British victory—at Plassey. To downplay Plassey is to downplay history.

TDS: What sources did you tap into for your research? What does your book add to this existing literature around the Battle of Plassey?

SC: Plassey, like all my books, required intensive and extensive research—and also much travel. I need to see, feel, hear, sense. The battle of Plassey is really a living history in the way we are affected by it and remember it. To me this required a mix of library research, books, monographs, articles and reportage—flavours gathered while visiting Kolkata, Murshidabad, towns and villages up and down the Hugli-Bhagirathi river, places in Bangladesh and Jharkhand. And, of course, Plassey itself.

Equally, it was for me important to go beyond English and Persian to include sources from France, the Netherlands, and Bangladesh—once part of greater Bengal, and look at poetry, theatre, folk theatre and cinema, to see how Plassey is portrayed, and why. I realised that several Company and British sources, even Persian sources, had only been partially plumbed. This offered a great opportunity to extract crucial information that has largely been overlooked. Only with this 360-degree approach could I make Plassey come alive in a comprehensive manner and, in the process, break several myths surrounding it.

Primarily, my book seeks to offer a balanced view. This approach is, to my mind, the appropriate way of treating history, especially an event as pivotal to India, Bangladesh, the subcontinent, in several ways even to British and Asian history. A balanced, corrective narrative is also the crucial need of the times, with so much partisan rewriting of history in the subcontinent, and so much 'saffron-washing' of history taking as in India.

And so, there is a crucial need to peel away layers to expose the truths and lies, the myths, and the nuances. The descriptions of Hapless Siraj, Crafty Clive and Treacherous Mir Jafar cannot be the only absolutes, because they are not. Moreover, the back story of Plassey, a mix of aggressive mercantilism married to geopolitics, is often diminished.

TDS: The afterlife of Nawab Sirajuddoula as a historical character is fraught with nationalist, imperialist and communal biases and prejudices. How does your book engage with this idea?

SC: To me Siraj-ud-daula is neither absolute villain nor tragic hero—and this opinion is gleaned from my research, not my emotion. He was a victim of circumstances of his own making as well as some beyond his control, such as dynamics unleashed by the crumbling Mughal Empire, and the geopolitical contest between Great Britain and France. Siraj was callow, somewhat impulsive, certainly spoilt, naturally nervous and tense, but hardly the martyred nawab or the illiterate and complete Caligula he is made out to be. And, as I like to mention, Siraj was 23 when he took over as nawab, and 24 at the Battle of Plassey. Imagine fresh post-graduate students in his place as nawab of Bengal, being jostled by Mughal pressure, Maratha pressure, a warring Britain and France, and powerful conspirators at his court, home and bank!

TDS: How is it relevant to discuss the events of Plassey now, particularly when the erstwhile subah of Bengal is fractured into two separate entities?

SC: To know our past for what it really was is as crucial as understanding our present for what it really is. Those who see history as a fantasy-factory, and the fundamentalists and ultra-right politicians who see history as an opportunity for pamphleteering, evoking hatred and seeking genocidal revenge, are the truest enemies of history. Certainly, the events of Plassey are rooted in schism. But they cannot continue to be a reason for schism. History is a tonic best used for learning, understanding, correcting, healing.

Watch a lively and more in-depth version of this conversation, conducted over Facebook Live, on The Daily Star and Daily Star Books Facebook pages, and the latters' Instagram page @thedailystarbooks.

Comments