The Ottoman Who Conquered History

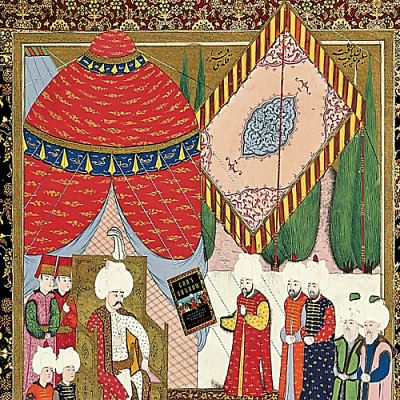

Yale University Department of History chair Alan Mikhail's new book God's Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World (Liveright, 2020) takes a much-welcomed fresh look at Selim I, a figure of signature cultural and historical importance in Turkish history.

Selim falls between two titanic figures in Ottoman history: his grandfather, Mehmed II, conquered Constantinople in 1453, in what Mikhail quite rightly calls an "earth-rattling victory, a conquest both actual and symbolic." And Selim's son went on to become known to history as Suleyman the Magnificent, "his legacy shaping the empire until its end in the 20th century." (And this is not to discount Selim's father Bayezit, who added ferociously to the empire's territories during his reign).

In writing what he refers to as a revisionist account of Selim, Mikhail seeks to rescue this pivotal figure both from the reflexive antipathy with which the West has viewed Islam and the Ottomans for centuries and also from the hagiography of the Selimnama (Mikhail styles it throughout his book as the "Selimname"), a collection of primary sources about Selim's life. Mikhail's organising approach here will strike many of those Western readers as astounding: "The ineluctable fact," he writes, "is that the Ottoman Empire made our modern world—which is, admittedly, a bitter pill for many in the West."

More than virtually any other single figure in its history, Selim expanded and solidified that empire in a series of battles and conquests that still make for stirring reading in the hands of an author as skilled as this one. Mikhail tells the story of the curious combinations that governed Selim's life: he was a scholar but also a merciless warrior; he was a sensitive poet, but also a tyrant who issued a death penalty for anyone caught using a printing press in his kingdom; he tried to adhere to a strict, warm morality, but his path to power was paved with dead bodies, including those of his own brothers and nephews. The shadow he casts over history is immense, and yet his reign lasted for only eight years, and when he died in 1520 he was still a fairly young man.

God's Shadow captures these and other seemingly contradictory aspects of Selim's life and rule with scrupulous scholarship and a storyteller's spirit.

Selim was born around 1470 as Bayezit II's youngest son, and Mikhail's narrative makes clear that the Selimnama's frequent allusions to Selim's will to rule are no mythological additions: ambition seems to have been his animating principle even from his early youth. His impatience with the preference shown to his older half-brothers is palpable in Mikhail's account; Selim filled a number of important military commissions on behalf of his father, but when he visited his father at the Topkapi Palace overlooking the Bosphorus in 1512, he had only one goal in mind. Mikhail relays the scene with delicate skill: "Speaking quietly, Selim presented his father with a dramatically insolent choice: either abdicate now—willingly, peacefully, and with dignity—and discreetly leave the palace for a comfortable retirement, or watch Selim's Janissaries seize the palace and empire by force, raving the city on their way," he writes. "Should Bayezit choose the latter path, Selim added, he could not guarantee his father's safety—or even his life."

Bayezit chose the better part of valour and became the first Ottoman sultan to leave the throne alive. At 46, Selim was finally ruler of the empire.

What followed was a series of iconic battles—the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, where Selim's forces, using guns and artillery, broke the growing power of Shah Ismail and gained his enormous territories in Iran, Azerbaijan, and Armenia; and the Battle of Ridanieh in 1517, where Selim wrested from the Mamluk Empire great swaths of land from Syria to Egypt (including Mecca and Medina). Through these and other key campaigns, Selim gave the Ottoman Empire a sprawl beyond even the dreams of his father.

As Mikhail makes clear throughout, he did it all with an eye turned warily on the West, to Islam's "civilizational kin and territorial rival", Christianity. God's Shadow does an invigorating job of redressing the balance between those two powers. As Mikhail puts it, "In the decades around 1500, it was not the Venetians nor the Spanish nor the Portuguese who set the standard for power and innovation; it was Islam."

Refreshingly, Mikhail broadens his account to defy the usual concentration that's so tempting when recounting Selim's turbulent life. God's Shadow gives us far more than simply Selim the warrior, mercilessly climbing to power and then mercilessly retaining it. Selim's territorial curiosity about the broader world outside his borders is given in fascinating detail, and Mikhail likewise paints a fuller picture of the sweeping legal reforms the sultan enacted throughout his broad domains. Mikhail doesn't look away from the key economic role slavery played in those domains. "Selim spent a hefty portion of his time managing the slave trade," we're told, "sourcing slaves, collecting taxes on sales of slaves, rooting out corruption in the marketplace, and keeping the flow of bodies moving through."

This portrait of Selim and the world he did so much to shape feels like a great gust of fresh air in off the Bosphorus. It's no hagiography itself—the Selim in these pages is, among other things, a brute and a slave-trader—and it all feels bracingly real.

Steve Donoghue is a book critic whose work has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, the Christian Science Monitor, the Washington Post, and the National.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments