'Desi Delicacies': Tracing South Asian Muslim civilisation through food

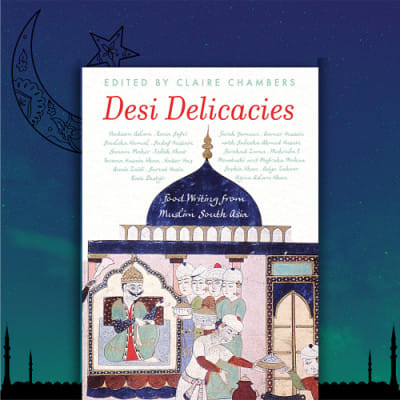

Desi Delicacies: Food Writing from Muslim South Asia (Pan Macmillan India, 2020) is a delightful anthology edited by Claire Chambers—no stranger to the lifestyle of Muslims. As a Professor of Global Literature at the University of York, she teaches the literature of South Asia, the Arab world, and their Diasporas. This collection brings forth our love for food, and as one goes through the 18 essays and short stories, they cannot help but admire the element of surprise they each have to offer, even for the most seasoned foodie.

The book divulges such secrets, like that of the yoghurt in subcontinental cooking, or the simple addition of a dash of turmeric during preparation and how it can make all the mouth-watering difference to a dish. This, the book tells us, is not just a matter of taste, but of culinary legacy. Chambers talks also about the slow cooking secrets of meat preparation in Pakistani households, and reveals how the potato entered the Muslim kitchen, becoming inseparable from the Bangladeshi kachchi or the quintessential samosa.

Each essay and story ends with a relevant recipe. The editor reminds us that in households of South Asia, "most recipes were passed down through the generations within the family and never written down with precise measurements". Yet, for the convenience of modern cooks, the recipes given do provide accurate quantities.

Does this take away anything from the alchemy that is this region's cooking? Maybe so, but this tweaking of South Asian culture is a necessary step in making the methods relevant to newer generations. This is why Desi Delicacies is more about the experiences attached to food, shared by the pool of writers in this collection, numbering 23. The language is straightforward. Its use of common Muslim words, often given without clarification or explanation, is expected to nudge the reader towards some curious fact finding. And instead of daunting the reader, it enhances the ambiance of a South Asian Muslim household. Much to the credit of Professor Chambers, this is one of the most attractive aspects of the book.

While the collection is on Muslim South Asian society, it breaks down geographical boundaries, simply because the food it talks of has done the same. It has been the attempt of the editor to not limit herself in chronicling a glorious past of Muslims. Her framework is set in history, but it is contemporary in nature as it divulges into the cultures of present day Lucknow, Rampur, Srinagar, Lahore, and Dhaka—the different seats of that glorious past.

The Muslims of this region bear the signature of a civilisation over a millennium in the making. Once they set foot in this region, they took inspiration from the richness of this land, and made significant contributions to local culture, most visible in its architecture and gustatory traditions. One noteworthy mention from the collection would be the essay "Jootha", in which Tabish Khair carefully outlines for us the division lines of inter-religion, and even intra-religion, that exist in and within the Muslim community, as is obvious in the food habits of its people.

Another example from our own country would be Kaiser Haq's writing on the delicacies of Bangladesh, known to be highly influenced by Mughal traditions, and steeped in Bengali heritage. Haq writes about the confluence of culture, in which Bengalis have known to harbour a love affair with both meat and vegetarian dishes, the latter often stemming from Hindu influence.

This, once again, shows that the Islamic civilisation is anything but monolithic, soaked in the legacy of its past, but quick to absorb anything around it. Thus, the "paye" is as much a Muslim food as it is Hindu; the "lotus stem" belong as much to the Kashmiris as to the rest of the subcontinent; and the "burger"—a term carrying heavy conotations in Pakistan—while a global phenomenon, has blended itself into the Muslim identity of the nation, giving rise to the so-called "burger generation" of Pakistan.

The politics of food takes a front stage in this book as it addresses the abhorrent social hierarchy that evidently existed and continues to exist in some Muslim households of the subcontinent. The stories often present this bigotry, subtle but clearly evident in the food practices of the community. This is what makes the book interesting. Full of mysteries from the kitchen of Muslim households of the Indian subcontinent, Desi Delicacies narrates the pathos and the glee food evokes in the minds of the people, numbering over a billion across the globe!

Mannan Mashhur Zarif is a senior sub editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments