War of attrition

A war of independence, lasting only nine months, proved time and again of the fighting spirit, resilience, and indomitable courage of Bangladeshis throughout history. From a strategic viewpoint, Bangladesh had little hope of putting up a defensive war. West Pakistan inherited not only a lion's share of military resources following Partition, but it continued to enjoy generous military aid from the US, which had allowed them to grow very powerful over a short period of time. In contrast, Bangladesh did not have an armed force. Despite all the obstacles, Bangladesh managed to end the war in only nine months, emerging victorious. How was this possible?

In searching for literature that covers the role of the Mukti Bahini in the victory of 1971, there is a noticeable dearth of objective analyses. Literature on warfare strategy is dominated by narratives of the 13 days of the "Indo Pakistani war". History would likely have been different if India did not enter when it did, allowing the resistance to engage in a direct frontal war with the Pakistanis on equal grounds. But the legacy of the Mukti Bahini is the true heart of our story.

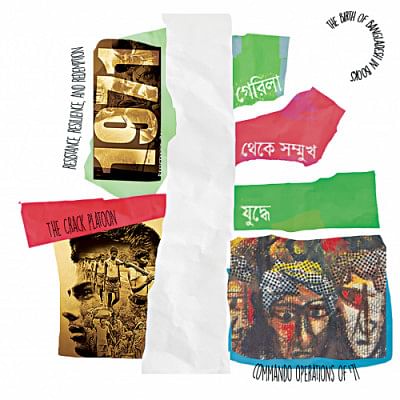

Books such as Guerilla Theke Shommukh Juddhe, Muktijuddhe 2 No Sector Ebong K-Force, 1971: Resistance, Resilience and Redemption, 1971: Bhetore Baire, and even bits and pieces of Jahanara Imam's Ekattorer Dinguli tell us the stories of the guerilla attacks, military strategies, and the progress of the war from the freedom fighters' perspective.

In March, a deus ex machina appeared as five of eight battalions of the East Bengal Regiment declared independence in response to Pakistan's March crackdown. As they became the nucleus of what would become the Mukti Bahini, the contribution of the Bangladesh Air Force, Navy, and Army along with the joined Armed Forces are also undeniable.

It was not just a war among fighters, it was a collective effort of the freedom fighters and general people alike. "We intend to make the whole nation a fighting force, the hard core being provided by the regular troops," said Khaled Mosharraf, sector commander of Sector-2 in a documentary. These words echo the broad strategy the top brass of this military nucleus had envisaged for the war. Given the exceeding limitations of time and resource, it was quite clear that the way forward was a prudent combination of conventional and unconventional warfare, with an emphasis on guerrilla tactics.

Written by Mahbub Alam, Guerilla Theke Shommukh Juddhe narrates the regular activities of freedom fighters in the form of stories. Mahbub Alam was the section commander of a freedom fighter unit in sector six, operating mainly in Thakuragon and Panchagarh. We know about the guerilla attacks and how they impacted the war in general, but Alam's book takes us through the actual course of events, guerilla attacks, sudden changes in plan, the aftermath of each attack, their consequences, and many more, all told through diary entries.

Mukti Bahini members came from all walks of life—they were farmers, day labourers, and students. Many wanted to fight, but in the absence of structured enrolment, the fighters began to coalesce into coordinated independent groups, known as the "irregular forces". Their leaders were not all military, but they commanded thousands, and their well-planned guerrilla operations managed to incapacitate Pakistani soldiers.

One name that comes to the mind is the Crack Platoon, a special commando cell composed of students, young professionals, political activists, and farmers led by Major Khaled Mosharraf. Their objective was to focus on commando operations inside Dhaka.

By targeting major structures inside the city via hit-and-run tactics, the Crack Platoon sowed terror within the Pakistani ranks. Their commando attacks became proof of an ongoing war to the outside world and their mission was to prove that the situation in Bangladesh demanded international attention.

But while the Pakistan army was employing Sabre jets and tanks, the Mukti Bahini had only the light weapons the revolting battalions had brought with them. More weapons would later be obtained from India. In the first week of April, India and Bangladesh decided to provide training to 5,000 freedom fighters each month, who would join the Mukti Bahini. In August, the number later increased to 20,000 freedom fighters each month. Several youth camps across the country were established to recruit young freedom fighters. Elected people's representatives were entrusted with the responsibility of recruiting these fighters.

Different and diverse seasonal changes in the environment also worked in the favour of Bangladeshi fighters. Deep rooted knowledge of the region, environment, and water bodies helped the Mukti Bahini to plan and execute guerrilla attacks efficiently and effectively.

"70-80% of the Freedom Fighters came from peasant background. Our history does not recognise their role properly," Air Vice Marshal (Retd) AK Khandker, Bir Uttom wrote in his book, 1971: Bhetore Baire. "We often forget that the Liberation War was a people's war and a national war." Indeed, a people's war in the truest sense, the liberation war will remain in history as a tactical success executed by general people from all walks of life.

Follow us on fb.com/dailystarbooks, @thedailystarbooks on Instagram, @DailyStarBooks on Twitter, and Daily Star Books on LinkedIn.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments