Where folktales meet social commentary

I stumbled across a short story written by Aoko Matsuda called "Quite a Catch" in the Wasafiri literary magazine last month. The story is a modern and feminist rendition of "Skeleton Fishing", a popular Japanese folktale that is often found in Bangla stories too. It is a haunting and delightful account of the female narrator "catching" lost skeletons while fishing. The skeleton, it turns out, belongs to a woman from centuries ago. This woman appears every night, caked with slimy mud, in the narrator's house, thanking her for rescuing her bones after so many years. She was slain by a man for rejecting his marriage proposal. With time, these women develop a romantic relationship as the narrator teaches her the ways of the modern world.

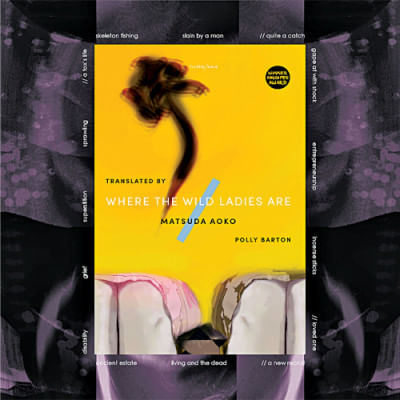

Reading this story, I could not help comparing it with the quiet eccentricity of Samanta Schweblin's short fiction collection, Mouthful of Birds (OneWorld Publications, 2019; tr. Megan McDowell). As someone who deeply admires the collection, I knew I had to read Matsuda's Where the Wild Ladies Are (Tilted Axis Press, 2020; tr. Polly Barton), of which "Quite a Catch" is a part.

The remaining short stories from this collection are also contemporary, feminist retellings of popular Japanese folktales—mainly the ones revolving around female ghosts who are traditionally seen in a villain's haze. Each story begins with a brief introduction on the folktale it draws inspiration from.

In Matsuda's world, ghosts are not supernatural entities one gapes at with shock. They are as mundane as startup companies and office employees. In "Loved One", for instance, one sees how grief blends with the blessing of entrepreneurship—a company sells incense sticks that revive a person's (dead) beloved relations. In the eponymous short story, alongside a few loosely connected others, ghosts manage office operations alongside mortal humans.

Here, ghosts—and other supernatural elements—are not bone-chilling characters deployed to intensify the horror genre. They are tools that shed light on mental health, grief, disability, belonging, deception, urbanisation, patriarchy, and violence. In "A Fox's Life", a hardworking woman suppressed by a patriarchal workforce turns into a fox—an allusion to her wit and cleverness. In "Enoki", a tree around which a sprawling body of local superstition has grown reminisces about the days when it was popular, revealing accounts of violence and blind, harmful prejudice. In "A Day Off" a woman forges an alliance with her giant pet toad to protect other women facing violence. In "A New Recruit", the narrator can see both the dead and the living as an ancient estate filled with departed souls, teetering on the brink of demolition. In "Having a Blast", a husband works at a company alongside his dead first wife; his second wife works alongside him when he, too, passes. In "My Superpower", an eczema-ridden writer can read people's minds.

What makes all these stories stand out is the subversive quality they all possess of cleaving a traditional narrative and rebuilding it as a mirror of modern society, all the while gripping readers into a frenzy of philosophical enquiries and suspense with candid, restrained, and unpretentious prose. From the very first story, "The Peony Lanterns", one grows keen to explore and completely lose themselves in Matsuda's topsy-turvy world. Not the slightest hint of boredom and dull descriptions of objects taints the pages; an endless flow of speculative elements—which are inherent in supernatural stories—keeps the narrative entertaining and suspenseful. At the beginning of each story, you think you are entering a normal setting but then something lurches forward and shatters your conviction.

With Polly Barton's agile and artful translation, Where the Wild Ladies Are teems with wit and invention. It is a must read for anybody who, like me, is a big fan of Mouthful of Birds or is simply into contemporary and disruptive retellings of folktales.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments