Whose Land Is It Anyway?

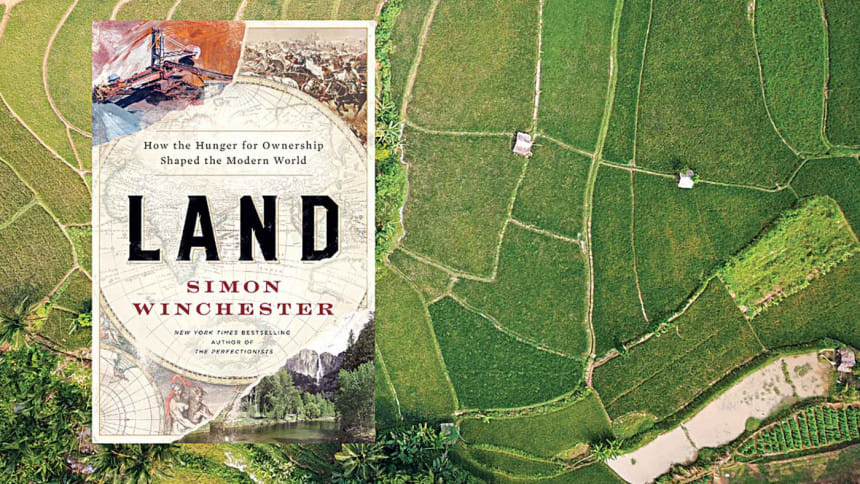

Land—its ownership, its deep history, its uses and abuses—forms the subject of best-selling historian Simon Winchester's new book, Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World (HarperCollins, 2021), which, given the topic, inevitably feels pitifully short at 400 pages. The subject of land is, after all, the stories of land, and there are as many of those as there are people in the history of the world.

Winchester is thus forced to concentrate, to isolate certain aspects of humanity's association with land and, in one of the book's many real estate-related figures of speech, drill down on those aspects to the exclusion of others.

One of his most effective focusing tools is his own land in Dutchess County, New York—its purchase, its title, its history, what it means to own it at all ("I had just purchased a piece of the United States of America," he reflects). The book begins, that is, with a simple land transaction—a familiar enough ceremony in life and literature.

This effectively underscores the ubiquity of the subject: no matter where you are when you're reading this, you're on land that's owned by somebody. Even if that somebody is you, that's not the final word. You almost certainly still need to continue paying for the privilege of occupancy, in the form of things like real estate taxes. And not all the mortgage payments or real estate taxes in the world will protect you if your government decides to exercise its version of eminent domain and simply seize that land out from underneath you for its own purposes.

One twist to the story that provokes Winchester's sarcasm and befuddlement is what he describes quite accurately as "land demarcation made insane." That story is, of course, Bangladesh, which inherited from the Mughal era a crazy-quilt of cross-purpose treaties and title deeds laid down onto what Winchester describes as "a landscape, with rice paddies and hills of the greenest beauty and loneliness, like nowhere else on the planet." When East Pakistan became Bangladesh, there were little bits of India still speckled here and there inside its territory. "And in one particularly and unutterably mad instance," Winchester writes, "a village of undoubted Indian ownership was inside a piece of Bangladeshi territory that was itself inside an Indian parcel that had been somehow pinioned inside Bangladesh." His comparison to Russian nesting matryoshka dolls seems like an understatement.

He notes, for instance, the fact that Britain's Queen Elizabeth II is one of the world's leading landowners, acting as "the owner of last resort" for the entire acreage of the United Kingdom, meaning that, "A quarter of the world's population lives on land in which, though the individual citizens may not know it, they exist in a notionally feudal relationship with the British Crown." Whether or not these claims would be a surprise to the Queen herself (or her army of solicitors) is surely secondary to the fun of the claim itself?

Winchester is a famously omnivorous writer. His dozens of books range over all of Creation and share nothing in common other than the most important things; a lively curiosity and a lively prose style. Readers have followed him to the eccentric personalities who gave birth to the Oxford English Dictionary, the planet-altering eruption of Krakatoa, to, more recently, the surprisingly widespread effect of precision engineers in modern history. This hopscotching approach has its weaknesses, of course: it tends to produce books that can feel scattershot, more conversational than scholarly (and that can lead to occasional slips, as when he asserts that the borders of the United States have "little or nothing to do with any physical need for separation," when in fact most US state borders are drawn along rivers or other physically separating features).

But the strengths of the approach are equally obvious: it's no small thing to sit down for a long conversation with a thinker and storyteller like Winchester, to find out what's on his mind this time, and which stories about his new subject have captured his imagination.

When it comes to the subject of land seen in its most general terms, the story seems to have a grim immediate future. Winchester concludes his book by noting that "the land is under threat like never before in human existence." Thanks to global warming, sea levels and tides are rising, and the pattern seems to have only one direction. "The trivial-sounding inundations of the recent past are recognized for what they were truly were [sic]," Winchester writes, "auguries of a certain kind of global doom."

His readers have already seen such auguries, in the daily news: disappearing ice shelves, super storms feeding off warmer ocean waters, eroding beaches and coastlines, shifting populations—all the signs of land under siege. It could well be that in less than a century, many of the distinctive charms of land described by Simon Winchester will be garish, or gone completely. But in the meantime, readers have this charming and challenging book as a snapshot.

Steve Donoghue is a book critic whose work has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, the Christian Science Monitor, the Washington Post, and the National.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments