Professor Nurul Islam’s Odyssey

This book is the story of Professor Nurul Islam, arguably Bangladesh's most famous living economist. The narrative begins with his early life in Chittagong in a middle class family—Nurul Islam's father was an educator. Professor Islam was a brilliant student, who did exceedingly well in his Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) exams which led to his admission to the famous Presidency College, Calcutta. From there he went to the University of Dhaka, and then eventually received a doctoral degree in economics from Harvard University, although, he tells us that initially, he was interested in studying accounting. After completing his studies in America, he joined Dhaka University as an associate professor of economics. Later he served as the Director of the Pakistan Institute for Development Economics (PIDE), being the first scholar of local origin, as well as the first Bengali, to lead this prestigious research body. After returning to Dhaka from Karachi, he played an active role in the struggle for economic justice for the Bengali people who were long discriminated politically and economically by the ruling class in Pakistan.

An Odyssey is essentially a memoir—the story of Professor Islam's personal and professional life and the intersection between the two, as told in his own words. He describes the book as a supplement to his previous book, Making of a Nation, Bangladesh: An Economist's Tale, which is a study of his association with the freedom struggle of Bangladesh.

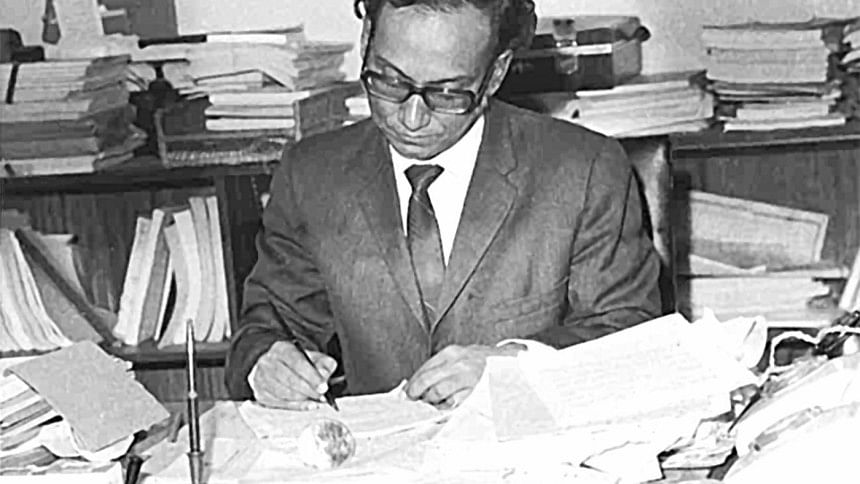

Professor Islam had an extraordinarily diverse career—as an university professor, the director of a research institution, a policy-maker, an expert technocrat, an international development expert, and a public intellectual. The book covers his career spanning over seven decades. For this memoir, he has depended on his papers and his memory, but prudently requests the reader for forgiveness if errors remain. He acknowledges that his version of events may differ from that of others—"Most or all individuals have biases—that is human nature" (p. 10).

In the first chapter, he discusses his early upbringing in Chittagong. He excelled in his studies leading to his outstanding performance in the HSC exams and then continued his studies at the Presidency College in Kolkata. There, as a Muslim student, he was in the minority among elite students from the influential Bengali Hindu community. To illustrate the social climate of the day, especially the sense of superiority of the older Hindus, especially Brahmins, he shares a story of his friend who had to suffer for inviting him to dinner at his home. The second chapter follows his move to Harvard University on a competitive government scholarship. He chose Harvard over Cambridge University in England, since for higher studies in economics, America had gained ascendency. He shares tidbits on fellow students he met on the Harvard campus, who later attained distinction. These include the young Zaki Yamani, the future oil minister of Saudi Arabia and the shy Karim Aga Khan, the future leader of the global Ismaili community. Chapter three reflects on his career upon completion of his Ph.D. at Harvard, when he returned to Bangladesh to join Dhaka University in 1960. The narrative captures details on the academic life of the nation's premier institution for higher education during the 1960s.

In chapter four, Professor Islam speaks of the set of accidental events that led to his appointment as the first "native" to lead the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), the nation's top research and planning organisation. His move to Karachi, Pakistan was an eye-opening experience. At PIDE, Islam was successful in attracting a galaxy of top international development economists.

As the political climate swiftly deteriorated, with increasing animosity between the East and West Pakistan, he was able to maneuver the move of the PIDE headquarters from Karachi to Dhaka, a remarkable feat. After his return to Dhaka (1969), he became closely associated with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was leading a successful political movement for the economic emancipation of the people of East Pakistan, which eventually led to the Liberation War of 1971. During the war, he managed to escape to India and eventually arrived in America. Soon after liberation in December 1971, he returned to help rebuild the new nation whose infrastructure and institutions were in ruins.

Chapter five describes his tumultuous years as the head of the first Planning Commission of Bangladesh, where he had assembled a team of top-notch economists and planners, who became known as "the professors". Interspersed throughout the chapter are details of his work, including interactions with his team, secretaries and ministers, and foreign officials. As the political situation worsened and the nation found itself in the grip of a tragic famine, he was among the last members of the core group to leave the Planning Commission, accepting a fellowship at Oxford in early-1975. Chapter seven captures his years as the Assistant Director General of FAO, based in Rome, and then his move to International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Washington DC. The last chapter covers his life among the Bangladeshi American community in DC, his retirement, and his writing.

It is well-known that Professor Islam played a key leadership role in the conception and elaboration of the Six Point Movement. This became the seed of the movement that eventually led to the Liberation War and the birth of Bangladesh as an independent nation. As the deputy chairman of the new nation's first planning commission, he played a central role in the conceptualisation and implementation of an ambitious plan to rebuild the war-ravaged economy and the nation.

After he left the planning commission, the political situation changed dramatically with the tragic assassination of Bangabandhu. He decided not to return to Bangladesh in a professional capacity. At UN/FAO and IFPRI, he dealt with agriculture policy at the national and international level. In retirement, living in Washington DC, he has continued to write about his long experiences in various roles. In a series of books and monographs he has shared his experience and the lessons he has learned. An Odyssey: The Journey of My Life, as an autobiographical volume, is a welcome addition to his remarkable story—a life lived in dedication of his profession and to his country.

Throughout the book, Professor Islam discusses some interesting people he had the opportunity to meet and interact with. Stories of many prominent individuals feature in these pages —some have passed away, while others are living.

ON THE INFLUENCE OF IDEOLOGY

Professor Islam addresses the widely-held perception that the first five-year plan of Bangladesh crafted under his leadership was socialist in nature. This perception is not surprising, since the Awami League government at the time did have a socialist bent. However, he argues that this view fails to account for the entire plan, which allowed a significant role for the private sector and businesses.

Interestingly, the word "socialism" does not appear in the index. The only related word in the index is "scientific socialism", which is used to describe the economic and political ideology of radical parties which gained some prominence soon after the Liberation War.

The author shares interesting facts and insights on the thinking and ideologies of members of the Planning Commission with whom he worked. He makes the case that the leaders of the first Planning Commission had economic and philosophical leanings that spread across the ideological spectrum. Discussing the nationalisation of major industrial enterprises, he writes, "I was concerned with the inefficiencies in economic management and was anxious to reduce them as far as possible." (p. 140). The entire book is filled with nuggets of wisdom on policies and strategies for development.

WAS THE FIRST PLANNING COMMISSION A SUPER-MINISTRY?

An Odyssey also addresses the perception among many that the first Planning Commission of Bangladesh was an all-powerful body—a super-ministry, which was run as a parallel government (p. 161–168). According to Professor Islam, this perception is a misreading of the facts on the ground. Why did the first Planning Commission become a target of criticism that continues to this day? He offers the following explanation. First, as it was constituted after liberation, the Commission was a major departure from what the ministries were familiar with. Second, during its rather short life, there was a significant expansion of the role of the state (ownership, regulations) in economic matters, and in administrative structures and rules, which was thought to be the result of work of the Commission. Third, the 1974 famine considerably eroded the popularity of the government, undermining its ability to manage the economy efficiently. Some of the blame for the famine and the mismanagement is placed on the Commission and its work. Last but not the least, the impact and negative perception of the nationalisation of several trading and industrial enterprises is also placed on the work of the Commission. (p. 165–166).

He proposes that Bangabandhu, an astute politician, interacted with a wide range of constituents which influenced his policy decisions. Even though Professor Islam attended cabinet meetings as the Deputy Chair of the Commission, it will be incorrect to say that the Planning Commission had monopoly influence over economic policies at the time.

Professor Islam is eager to address the question why he and other experts left the Planning Commission soon after the plan was completed in 1973 (he was the last to leave). He writes, "By mid-1973 after the Five-year Plan was finalized, my colleagues and I concluded that we were not very happy with our life in the Planning Commission." (p. 195). He admits frankly that the reason was the team's inability to act as politicians. "This was partly because of our lack of skill or temperament in the art of persuasion or negotiation or in making alliances for the acceptance of our suggested policies or programmers". (p. 195). This may also be the reason why he decided not to return to work in the public sector.

The author writes that Bangabandhu at times was extremely frustrated with the slow pace of policy implementation—despite his enormous prestige and power, the quality and competency of the bureaucracy had often stymied him. The PM wanted to build Bangladesh's foreign policy as a neutral one, similar to that of Switzerland. In an extensive passage (chapter five), Professor Islam addresses the issue of the influence of India on early policy-making in the newly liberated Bangladesh. Despite the popular notion, he stresses that India had not taken advantage of Bangladesh in those vulnerable years. He writes that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had great respect for Bangabandhu and had tried her best to help and support him. However, there were some in the Indian civil service who were not so inclined to help the new nation. (p. 171–183).

What makes the book interesting are the many stories, episodes and characters about whom the author writes. Reading the book, one finds important details about major events in the history of Bangladesh right from its inception. Interspersed with these, there are stories, often not yet in the public domain, about people and personalities that played a key role in the early history and development of the nation.

He also writes about the trials and tribulations his family faced, as he worked tirelessly to help rebuild his country. On a lighter note, he writes about the many fascinating places he visited and people he met—some who helped him in his mission and others who opposed him. All of this he writes without malice or judgement, and generally presents arguments from more than one perspective. It will come as no surprise to those who have interacted with him that he enjoys asking questions even as he offers answers and solutions.

Towards the end, he writes wistfully of the "moments of happiness and accomplishments" and those of "disappointment and frustrations". To quote him, "Many things in my life, both good and bad, had happened as a result of chance and circumstance." (p. 274). In a frank passage, he shares his feeling of ambivalence about whether he had made a mistake in accepting the position of the Deputy Chairman of Bangladesh's first Planning Commission. One reason is that "academics in the Planning Commission headed by me were 'outsiders', who did not belong to the bureaucratic and political establishment of the day; we became an easy scapegoat to blame for the mishaps and economics of the period…" (p. 274).

An Odyssey: The Journey of My Life is written in an easily readable style, free of economic jargon. It is a must-read for anyone who is interested in the history of Bangladesh. Here is a first-hand account of someone who has been an "eyewitness" to many of the major events in the early life of the nation before and after its birth, as it fought for its survival and its move to a stable and mature economy.

I would recommend the book to everyone interested in the political and economic history of Bangladesh during its early formative years. The reader will find many nuggets of wisdom from the life and remarkable career of Professor Nurul Islam.

Munir Quddus is Professor and Dean, College of Business, Prairie View A&M University and President, Bangladesh Development Initiative (BDI).

Email: [email protected]

Comments