‘All Quiet on the Western Front’: Reverberating despair and dread through a theatrical production

All Quiet on the Western Front (Little, Brown and Company, 1929), a semi-autobiographical novel authored by a German World War I veteran, Erich Maria Remarque, is one of the greatest anti-war works of literature—one that was published nearly a century back and still holds relevance today. The 2022 film adaption on Netflix, directed by Edward Berger, is nothing short of a cinematic masterpiece, and so visceral and marrow-chilling is its realistic portrayal of the horrors of trench warfare that it kept me glued to the screen all throughout. To that end, I didn't miss the chance to watch a Bangla dramatic adaptation at the National Theatre, Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy last weekend. Having watched seasoned director Bakar Bakul's three other plays in the past, I knew it would be an experience I wouldn't want to miss.

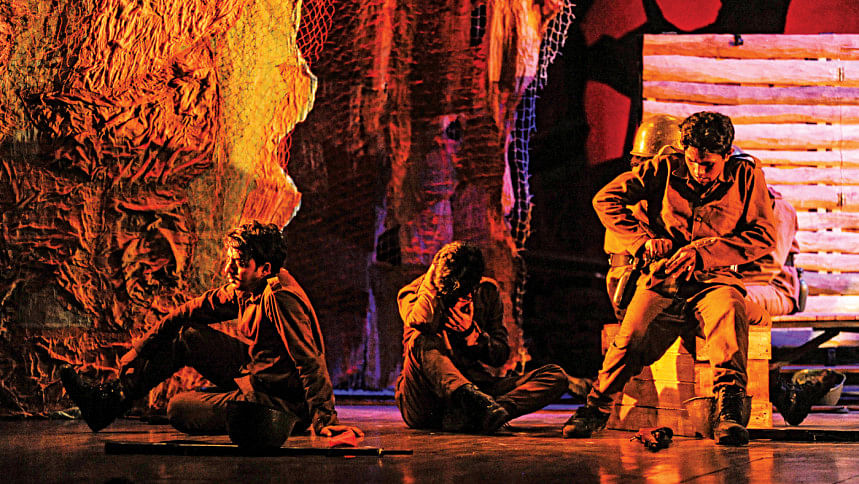

I'm not certain what made Bakul choose such a text (adapted for the stage by Runa Kanchan) for theatrical production, given how difficult it may be to present scenes from the frontlines and the German trenches on to the confines of a stage, but the set design, lighting, sound effects, costumes, and props created an immersive and realistic experience for the audience. Visual representation such as dilapidated trench walls that were barely shielding the unprepared, untrained, underaged child soldiers, auditory elements such as artillery fire and bombardments, and atmospheric effects such as the use of smoke were thoughtfully utilised. Moreover, the juxtaposition of dim, cool lighting to evoke the destitute condition of the soldiers and harsher, dramatic lighting to convey danger and threat left a beautifully disturbing impact. And lastly, the most magical stage prop was the drop of a larger-than-life pendulum at the center of the stage, one that swayed to and fro–covering the entire length of the stage's backdrop–reminding both the characters and the audience that the war was almost over, and at the same time, bringing about a feeling of dreaded suspense.

Certain conversations and dialogues have remained with me and I'm sure they had a similar effect on everyone in attendance. For example, when a soldier dies, he is just a cadaver to be left to rot and not something to risk one's life for in the hopes of giving it a proper burial; friendship "doesn't matter" during a "bloody war".

As far as the plot goes, Bakul did justice to the original, portraying how war propaganda drove teenage boys to get enlisted at a time when men were scarce. "Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori"—"it is sweet and fitting to die for one's country"–a quote from the Roman poet Horace, was taught to the German school boys, and they didn't know any better. After all, it's not like the reality of war was publicised and information wasn't at their fingertips as it is today. The enchantment of becoming men in uniforms drove naïve boys to assume that the war was more like a rite of passage or a show of machismo—one that they would surely win and come back from as glorious victors/heroes, worthy of the attention of young women. Little did they know that they'd have to bury everything that made them human, i.e., their conscience, will power, and humaneness, and become more like programmed robots or puppets—mere pawns that were to blindly carry out orders in an abominable hellhole that they couldn't have fathomed even in their worst nightmares. The losses of both bodily autonomy as well as boyish innocence were heavily highlighted in multiple scenes. And so, instead of becoming the strong men they aspired to be, the characters became tormented souls, not knowing if the next minute will be their last, and in one instance, walking right into a death trap, as a result of being driven mad by the overwhelming distress of it all.

Certain conversations and dialogues have remained with me and I'm sure they had a similar effect on everyone in attendance. For example, when a soldier dies, he is just a cadaver to be left to rot and not something to risk one's life for in the hopes of giving it a proper burial; friendship "doesn't matter" during a "bloody war". Empathy for a comrade soon disappears when a soldier loses a leg and has no use for the good pair of boots his mother had given him; his boots become the subject of selfish interest, while his painful cries fall on deaf ears. In another scene, the soldiers don't even know what started the war and the reason itself—that one nation had insulted another—is so ridiculous that they laugh an eerie laugh, which left me unnerved. War is an instrument to bring fame to politicians and "war is just a fucking business" for the weapons industry. When Paul, the protagonist, knifes a Frenchman, he is engulfed in remorse. He wonders if a different uniform is all it takes to make another man his enemy. He says, quite emphatically, "War is nothing but murder"—a universal truth that can be applied to the wars and genocides we come across in the news every day. Interestingly, audience members were given a "Daily Bullet-In" (a play with words), designed to look like a newspaper, which has headlines and pictures of the murderous wars Paul refers to.

As for any constructive criticism I may have to offer, in scenes involving actors who were supposed to speak in French, they spoke mostly gibberish. The actresses playing the role of French girls in particular couldn't even mimic French intonation or accent. That being said, the fact that there was a gutsily-choreographed, heated love scene between German soldiers and French girls that bordered on soft-porn sent home the message that human cravings to be touched, felt, and loved cannot be withheld by differences in race or language barriers. And finally, at the end, when Paul is fatally shot ironically at the moment when armistice is declared, his metamorphosis into a supposed dancing Monarch butterfly added a nice choreographic touch, but the Casper-the-friendly-ghost-like costume seemed a little off. Perhaps a white shroud was what the director had in mind?

The amount of physical and mental energy the actors had to exert into putting up such a stellar two-hour-long performance is truly commendable. The actor who played the role of the German General in particular, despite being a flat, side-character, was possibly my favorite, because he managed to instill a strong sense of hatred towards his character, given that he was the indefatigable puppet-master and the sole reason why ceasefire was not declared earlier.

Noora Shamsi Bahar is a senior lecturer at the Department of English and Modern Languages, North South University, and a published researcher and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments