A Bengali Buddha in Blighty

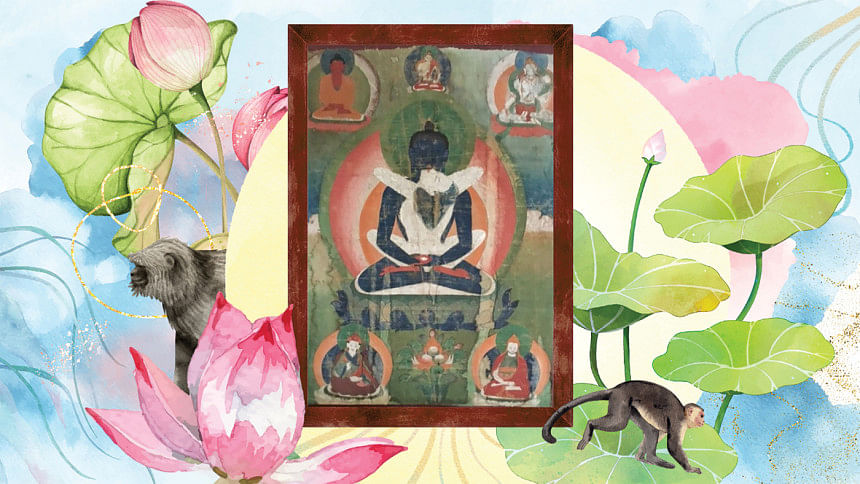

Pride of place above the fireplace in the sitting room of our little house in distant Blighty is a painting from North Bengal. It is of the Buddha, an image dating from before the time of the coming of Islam to Bengal when, during the Pala dynasty, great centres of Buddhist learning flourished at sites such as Paharpur, then Somapura.

Sitting on the mantelpiece below the Buddha are half a dozen ceramic monkeys sculpted by an artist from Madhubani schooled in Shantiniketan: arms outstretched, the banara lok are searching for the kidnapped Sita. To either side of this central fireplace are shelves stacked with books.

This library includes a huge family Bible, Mohammad Marmaduke Pickthall's explanatory translation of the glorious Qur'an and the Bhagavad Gita. Beyond these sacred scriptures extend the profane, ranging from the seminal works of Sir William Jones (longtime resident of Bengal interred in Kolkata) to those of Kaiser Haq on the topicalities of Greenland and the streets of Dhaka.

As for art, besides the thangka of the Buddha and the glazed monkeys, there are colourful paintings and sculptures of the mischievous Krishna and several of my wife Rani's watercolours of idyllic Indian pastoral scenes. An assortment of easy chairs and much other bric-à-brac lend comfort to this cosy sitting-room.

Pleasant as this refuge may be, it begs the question of where in all these possessions the truth of life may lie. Does one need all these books? My father had few books: not many beyond Shakespeare, Dickens and Boswell's Johnson. My maternal grandmother's legacy was just that one big family Bible, names inscribed inside, together with an equally weighty copy of John Bunyan's allegorical guide on how to live a dutiful Christian life, The Pilgrim's Progress (1678).

How many books does anyone really need? Where is wisdom to be found? As the philosophers ask: Is the One to be found in the many or the many to be found in the One? The Qur'an would no doubt be "the one book" sufficient for many pious folk in Bangladesh as the Bible was for my grandmother.

Some have questioned what need there is for commentaries on such divinely-revealed texts? What need of commentators or interpreters: scholars, imams, priests? Others, going further, ask 'what need of any books at all, however sacred and seminal?' Is it not, as the practices of the Sufis and Vaishnava Bhaktins of Bengal have suggested, that truth is to be found, if not in the mind through meditation, in the depths of the human heart?

And as for books, so for images, whether paintings or sculptures, to say nothing of photographs and those selfies that epitomise the headlong rush into irrelevance of a consumer society. At various times in history the two later religions of the Book have both adopted the original Judaeic prescription banning graven images.

Islam's traditional prohibition on representational art is well-known but a similar concern has also surfaced in Christianity. In 8th century Byzantium–later Constantinople and finally Istanbul–there was a mighty struggle between the Iconoclasts and the Iconodules of the Orthodox Church, those who would destroy sacred images as profane distractions and those who advocated their devotional value.

With the rise of Protestantism in 16th and 17th century England, the Puritans quite literally attacked Roman Catholic "idolatry", engaging in the systematic smashing of the stained-glass windows of churches and of any and all paintings and statues depicting religious figures. The windows they replaced, if at all, with clear glass. Some, abandoning chapels altogether, gathered to worship under yew and oak trees in the open fields.

So where does all this leave the Bengali painting of the Buddha above our fireplace? Years ago, on account of my wife being an exotic Indian visitor, it was given to her by a Dominican monk in a monastery in Avila in Spain, a city once under Muslim rule and later the home of the Christian mystic, Teresa. The iconic painting, though badly water stained, has materially survived its wanderings in various hands through various lands but what, if anything, has survived of its spiritual significance?

With one crucial difference, the painting resembles the many familiar images there are of the Buddha, the enlightened–or disillusioned–one, in a state of meditation or trance. The difference is that seated in the lap of this–indigo blue coloured–Buddha is the white image of a female Shakti in an apparently perfect position of or for sexual congress.

If Buddha represents the principle of absolute quiescence, śunyata or "emptiness", detachment from the desires of life, Shakti represents that of energy and life in all its fullness. The two are perfectly if paradoxically reconciled or fused in this Tantric image that, make of it what you will, is designed to expand the mind.

Meditate for a moment on this blissful image of the Bengali Buddha and it promises or threatens to transform or supplant the domestic scene over which it presides. If we had to imagine a close counterpart, even embodiment, in contemporary Bangladesh would it not be the figure of the baul, wandering the byways free of the desire for household possessions, the devotional songs he sings a manifestation of his inseparable Shakti?

John Drew is author of India and the Romantic Imagination (Oxford India). A selection of his contributions to the Literature page of The Daily Star has been published as Bangla File (ULAB Press).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments