Between protest and power: Shahriar’s portrait of a nation in flux

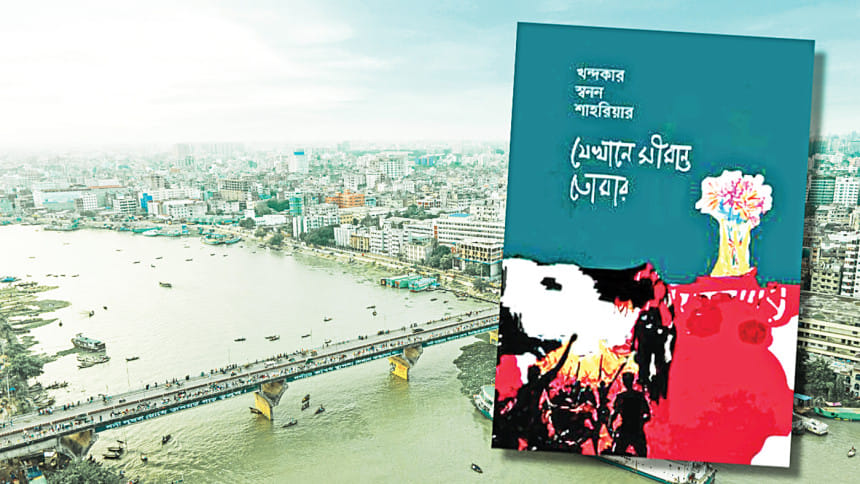

Literary experts often caution against writing a novel immediately after a major political upheaval, arguing that personal involvement may cloud objectivity. However, creative minds are seldom bound by such prescriptions. Just as Shaheed Anwar Pasha authored Rifle, Roti, Aurat (first published in 1979) during the Liberation War, Khandker Swanan Shahriar felt compelled to write his second novel, Jekhane Shimanto Tomar, stirred by the events surrounding the July Uprising. Wrestling with his inner dilemmas following the days after August 5, Shahriar wrote this novel as an urgent response to history in the making.

While Pasha offered a powerful, empathetic, and humanistic portrayal of the circumstances during the liberation war, Shahriar takes a more critical stance on the Uprising, attempting to unmask the limitations and contradictions of all stakeholders involved. Jekhane Shimanto Tomar weaves together multiple subplots or parallel narratives to present a holistic account of the 'July 36' events and to document the broader context of 15 years of quasi-fascist rule under the Hasina regime.

One narrative thread follows Mojaffor Hossain, a Member of Parliament, and his daughter Ania. Through them, the author illustrates the misuse of political power: Mojaffor extracts commissions from public projects, arranges for the arrest of Ania's ex-boyfriend, and manipulates systems to secure her a position at a prestigious institute. The novel lays bare how traditional Bangladeshi politics often enables land grabbing, extortion, and environmental degradation, such as river-filling, by party loyalists.

Yet, the novel does not flatten its characters into mere villains. Mojaffor, once an honest politician, is shown as a man trapped in the vicious cycle of power politics—much like the July frontliners themselves after forming a political party. He is contrasted with his old friend Kamalesh, a freedom fighter who leaves the party after witnessing its degeneration. Ania, in turn, disapproves of her father's abuse of power and develops admiration for Kamalesh and her grandfather, both of whom embody integrity and patriotic love.

Through Ania's visit to her ancestral village and conversations with Kamalesh and his comrades, the author unveils the regime's track record of corruption: extortion, manipulation of public tenders, three uncontested elections, embezzlement in mega-projects, systemic bribery, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and the stifling of dissent—all facilitated or overlooked by law enforcement agencies.

Another significant subplot revolves around Mujtaba, a student, and Regan, the son of a former opposition MP. The author critiques the toxic culture of student politics, especially the persecution of students who visibly express Islamic identity, such as by wearing beards or topees. Mujtaba is expelled from his university dormitory under false accusations of political affiliation and later becomes ensnared by Regan's ideological network. Regan exploits the vulnerability of disenfranchised students and manipulates them into joining his cause with enticing rhetoric. In a conversation with Mujtaba, he declares (as translated by the reviewer):"Ideology is just a pretext. What politicians really want is power. They seek to reclaim it when out of office and cling to it once they have it. Once secured, they exploit it—for themselves or their party. The difference between good and bad politicians is merely in how easily their deceptions are recognised."

This subplot underscores the necessity of the Quota Reform Movement while simultaneously revealing the movement's susceptibility to infiltration. Trained political actors are shown looting weapons, vandalising monuments, torching politicians' homes, and terrorising innocent family members. As we see, Mojaffor's house is looted, vandalised, and set ablaze; his guard is killed, Ania flees to India, and Mojaffor escapes to Singapore earlier.

Yet another narrative follows the tragic love story of Harun and Shahida. When Harun attempts to marry Shahida, Jobed—Mojaffor's assistant—has him falsely imprisoned using political influence. Jobed then marries Shahida, who is already pregnant with Harun's child.

Though the novel celebrates the spirit of the movement, it also critically explores the moral ambiguities and personal failures of its participants. It was published during the last Ekushey Book Fair, sounding an alarm for all political actors to confront their own ethical boundaries and complicity. As readers, our continued disregard for such critical fiction and essays risks normalising fascistic tendencies—extortion and stoning to death, mob lynching, summary executions, historical revisionism, media trials, nepotism, censorship—all of which persist in different guises today.

The prose is lucid and accessible, somewhat reminiscent of Humayun Ahmed's signature style. Shahriar even adopts some "Humayani" trademarks. The narrative unfolds through parallel storylines, creating an engaging and layered reading experience. The book's structure mirrors its title, Jekhane Shimanto Tomar (Where Your Limits Lie), dividing the novel into chapters with evocative titles, some borrowed from famous songs like "Nongor Tolo Tolo", "Pother Klanti Bhule", "Dorjar Opashe", "Peye Haranor Bedonay", among others, enriching the emotional texture of the narrative. At the beginning or end of chapters—and during narrative shifts—the author incorporates symbolic imagery and language, often hinting at impending doom or its reversal.

In sum, this novel takes the reader on a journey from 2010 to a reimagined Bangladesh, offering not only a reflection on the past but also a vision of the future. It presents poignant observations and raises critical questions that remain unanswered even a year after the July Uprising. It demands that we not only witness history but question it—and, perhaps, change its course.

Mohin Uddin Mizan is a publication and communication professional at the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS), Ministry of Planning. A translator and former journalist at national dailies, Mohin used to write short stories, poems, op-eds and book reviews for print and online platforms at home and abroad. He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments