Of women, rage, and what burns unseen

"Hakhdaar tarse toh angaar ka nuuh barse…"

(If the one who has rights is displeased, a rain of fire will fall)

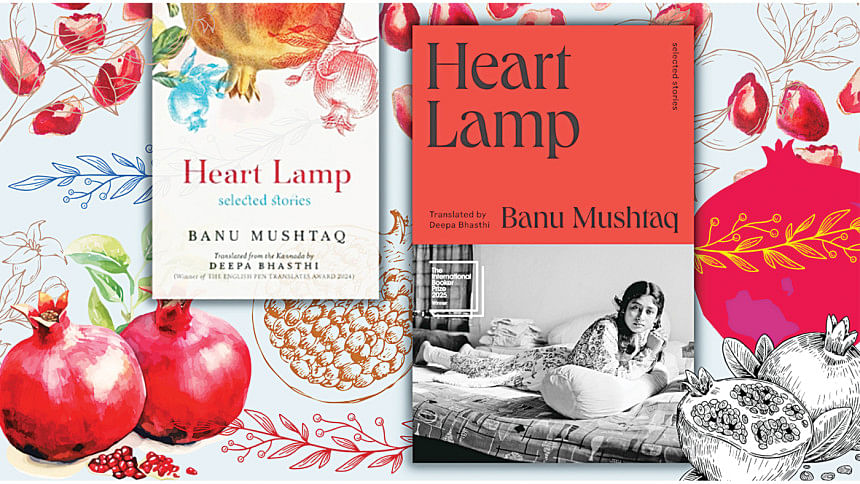

—This quote, from the story "Fire Rain" in Heart Lamp, sets the emotional temperature of the entire collection.

There are books that try to rebuild the world. There are books that try to explain it. And then there are books that do neither; they just hold up a mirror. Heart Lamp is that mirror. It does not seek to heal or to reconcile. It simply insists you look. It speaks of smoldering anger—not the kind that explodes, but the kind that simmers in silence, tucked away inside generations of women who have been denied dignity, voice, and justice. Banu Mushtaq writes about the displeased; about those whose pain society has normalised, whose lives are shaped by absence: of choice, of power, of recognition.

Heart Lamp, which recently won the 2025 Man Booker Prize, is a curated collection of 12 short stories written between the 1990s and 2023. Selected from the best of Mushtaq's literary career, these stories center the everyday lives of women from Kannada—particularly Dalit and Muslim women—whose experiences are shaped by caste, religion, poverty, and gendered violence. The collection's core themes include reproductive rights, patriarchy, societal traditions, and the subtle yet violent mechanisms that control and erase women's agency.

Again and again, we witness women trying to reclaim control: some wanting to undergo sterilisation without their husbands' permission, some demand their right to inheritance, others quietly but firmly refuse to return to homes where they've endured years of mental and physical abuse. These are not grand acts of revolution, but small rebellions of survival, each one cutting into the social fabric that seeks to bind them.

The opening story, "Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal", lays the foundation for the collection's recurring themes: reproductive injustice, domestic labour, and the normalised disposability of women. Shaista, a woman who bears seven children in quick succession, dies soon after childbirth. But her death barely disrupts the rhythm of her husband's life; he remarries a younger woman to care for the children, stops his eldest daughter's education to manage the household, and moves on. The story doesn't dramatise this; it simply presents it, as if to say: this is what happens, every day, everywhere. In "Fire Rain", Mushtaq turns her focus toward inheritance and religious hypocrisy. The story revolves around the Mutawali Sahib—a man tasked with overseeing religious matters in the village—whose sister dares to demand her rightful share of inheritance, even citing verses from the Quran itself. His rage isn't just personal; it's cultural, political, and performative. He is more concerned about doing charity, involving himself in political stunts and maintaining his prestige in the village than practicing justice within his own family. Though written in the 1990s, the story painfully mirrors present-day realities where women still fight for the bare minimum, and even scriptural legitimacy is not enough to earn them their due.

At times, the stories and the plot of the book feel repetitive; again and again, women face versions of the same suffocation. Yet, repetition is the point—it builds into a collective portrait of women's lives, showing just how relentless and normalised the violence against them is. Even in this overwhelming similitude, though, Mushtaq refuses to strip her characters of agency. Again and again, we witness women trying to reclaim control: some wanting to undergo sterilisation without their husbands' permission, some demand their right to inheritance, others quietly but firmly refuse to return to homes where they've endured years of mental and physical abuse. These are not grand acts of revolution, but small rebellions of survival, each one cutting into the social fabric that seeks to bind them.

The titular story, "Heart lamp", stands as a devastating example of this tension between endurance and collapse. Mehrun, the protagonist, finally decides to leave her husband's house after facing repeated abuse. But when she returns to her family, instead of support, she is met with cruelty. She is labeled a disgrace to womanhood for failing to "keep" her home, her marriage, her man. Her suffering is seen not as a wound but as a shameful mark she must carry. Forced to return to the very home she fled, something inside Mehrun breaks. The lamp of her heart—once flickering with hope, perhaps for her children, perhaps for a different life—goes out. Her act of burning herself isn't framed as a moment of weakness, but as a final response to a world that gave her no other way to be heard.That too, Mushtaq tells us, is what society can do to a woman: not just silence her, but hollow her until she no longer recognises herself.

As the collection unfolds, Mushtaq adds layers of complexity to her narrative world. While the focus remains on women's lives, some stories reveal how patriarchy entraps men as well albeit differently. In "Red Lungi", she examines how blind faith can fuel inhumanity, showing how belief systems, when unchecked, become dangerous. In "A Decision of the Heart", the protagonist Yusuf arranges the marriage of his widowed mother who is nearly 50 years old, not out of empathy, but as an act of quiet defiance against his own wife. These stories subtly highlight how even within patriarchal structures, men, too, are shaped, sometimes twisted by the systems they benefit from. Suffering is not always one-dimensional, and Mushtaq allows room for this complexity.

The collection concludes with "Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord", ending on a haunting invocation: "If you were to build the world again, to create males and females again, do not be like an inexperienced potter. Come to earth as a woman, Prabhu! Be a woman once." It encapsulates the deep exhaustion and quiet rage of women who have been sidelined for generations by poverty, caste, gender, religion, and societal norms.

Building on the book's deep-rooted connection to community and resistance, the translation by Deepa Bhasthi plays a vital role in carrying its essence to a global audience. Rather than erasing the linguistic texture of the original, she preserves its multilingual spirit—retaining Urdu and Arabic words without flattening them into English, and embracing the natural hyperbole and repetition found in everyday speech. She also resists the colonial convention of italicising non-English words, refusing to mark them as "other." This approach not only honored the linguistic richness of southern India but also carried forward the spirit of protest and resistance embodied by the author, Banu Mushtaq, a key figure in the Bandaya Sahitya movement that challenged upper-caste, male-dominated literary spaces.

Banu Mushtaq writes as someone who has lived what she tells. She is both a lawyer and an activist from the communities she portrays in her stories, stories that are shaped by what she has seen, lived through, and fought against. They do not rely on dramatic villains or heroic figures; instead, they unfold through the quiet tragedies and daily negotiations of women navigating unjust systems. That is the quiet power of Heart Lamp—its ability to find meaning in the mundane, to expose how normalised cruelty and silence can be, and to speak of lives that are often spoken over.

Mahmuda Emdad is a women and gender studies major with an endless interest in feminist writings, historical fiction, and pretty much everything else, all while questioning the world in the process. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments