No bank fees, please: Central Bank Digital Currency will deliver remittance like emails

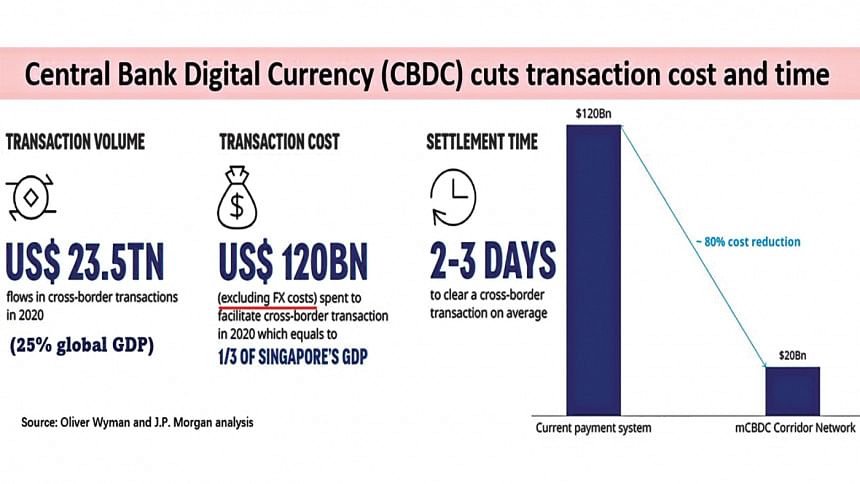

Cross-border payments are inefficient, often slow, opaque and expensive. Worldwide businesses did $23.5 trillion cross-border transactions in 2020, which is equivalent to 25 per cent of global GDP. The businesses have also paid bank fees of $120 billion (excluding foreign exchange conversion costs), which amounts to Singapore's one-third of GDP, said a recent J.P. Morgan analysis.

That is business-to-business payments. In person-to-person transactions, the migrant workers sent $551 billion homebound remittances in 2019. Intermediary bank fees of these payments have averaged 6.8 per cent, or $37.5 billion, revealed a March 2021 report of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), quoting the International Monitory Fund and the World Bank.

In response, the BIS is stewarding the distributed ledger technology-based Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) to bring down cross-border remittance costs. And the J.P. Morgan report says that businesses could save 80 per cent of annual intermediary costs ($100 billion) if CBDC is applied in cross-border payments.

CBDC is a highly secured digital version of a country's official currency. Bypassing commercial banking system, citizens will have individual accounts directly with central banks. And they will use "retail CBDC", instead of paper money, for all payments. Digital mobile wallet will be their tool of such transactions.

Corresponding central banks set mutually agreeable conversion standards of respective CBDC and bypass intermediary banks for cross-border transactions. Time to settle the businesses' and migrant workers' payments would be as instantaneous as exchanging emails because the CBDC-based payment systems operate round-the-clock and throughout the year.

The 63-member BIS is setting out common foundational principles and core features of CBDC. Its primary mission is to contain the anarchic rise of blockchain-based cryptocurrencies. A 2021 BIS survey has found that 86 per cent central banks are actively researching the potential for CBDCs while 60 per cent were experimenting with the technology and 14 per cent were deploying pilot projects. But tangible outcome of the western central banks-led CBDC initiative is actually coming from the unassuming communist China.

People's Bank of China (PBOC), the country's central bank, launched CBDC as digital yuan (e-CNY) in April 2020. More than 20 million e-CNY wallets have been created and $5.4 billion or 35.5 billion yuan has been settled in China's CBDC network, said PBOC's July 2021 report.

Beijing has already told McDonald's to adopt e-CNY payments system at all outlets nationwide ahead of the Winter Olympics in February 2022. Authorities have also asked Visa, a top Olympics sponsor, and Nike, a US team sponsor, to follow the hamburger chain and integrate e-CNY in their payment systems.

Four BIS-led projects exploring CBDCs for cross-border payments are also underway. They are assessing if CBDC allows transactions to be settled "more cheaply and easily". The central banks of Australia, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates are engaged in these four groups. Regrettably, no South Asian central bank is visible in this mission.

Nevertheless, Bangladesh Bank (BB) data shows a brisk 36 per cent uptick of inward remittance in 2020-21 fiscal year. Average cost of sending 200 US dollars was 4.9 per cent while remittance originating from Singapore and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries costs below 3 per cent, according to the World Bank.

But such costs are well over 10 per cent when the remittances are routed through highest-cost banking corridors.

The BB has received more than $24 billion remittance in 2020-21 and 57 per cent of it ($14.3 billion) came from Singapore and GCC countries. But the remaining 43 per cent ($10.6 billion) came through the highest-cost corridors, incurring more than 10 per cent intermediary bank charges. And that is more than $1 billion collective loss to the Bangladeshi migrant workers and the country's reserve.

Remittance inflow through formal channels grew by 11 per cent in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019-20 fiscal year. But it leapfrogged by 36 per cent in the following fiscal year, as the pandemic has incapacitated the informal money movers. The government has also incentivised remittance through formal channels.

As a result, the annual growth of inflow jumped from the major sources of remittance for Bangladesh in 2020-21. Some $3.5 billion came from the US (44 per cent growth), and Malaysia and the UK posted 63 per cent and 48 per cent growth, respectively, with each pumping $2 billion. Australia's $142 million (141 per cent growth), Japan's $80 million (61 per cent growth), and Italy's $810 million (16 per cent growth) contributed to the higher receipts.

Leading mobile financial service bKash has disbursed $134 million of remittance in 2020 and it expects to post 87 per cent growth this year by pumping $250 million. Extensively located nationwide MFS outlets like those of bKash have set the stage for domestic and cross-border CBDC in Bangladesh.

Market navigates technology towards unintended consequences. GSM technology was developed as a pan-European mobile telecoms standard. But it became the developing world's lifeline for universal access to telecoms. Subsequent introduction of mobile financial service became the revolutionary unintended crucible of universal access to banking. The fusion of internet and smartphone has now made talking, texting and video conferencing absolutely free.

Similarly, the world's leading governments' mission to dwarf cryptocurrencies with CBDC is poised to cross-pollinate with unimaginable unintended consequences of instantaneous settlements within and beyond political borders.

The Bangladesh Bank should get actively engaged with the BIS to execute CBDC following the steps of its Asian peers. The goal should be to fix billions of dollars' leakage in the pipelines of inward remittance. Stopping further billions of dollars' hemorrhage from export-import settlements will strengthen the country's financial health. And CBDC will concurrently unshackle the migrant workers and businesses from the market failures of conventional banking for good.

The author is senior policy fellow at LIRNEasia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments