Inflation falls but still at an elevated level

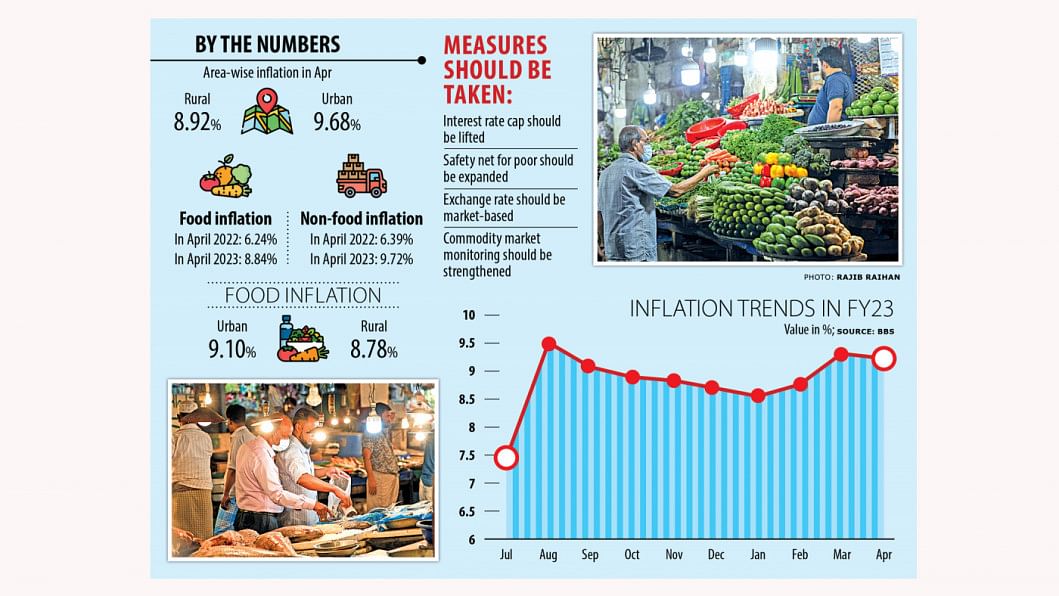

Inflation in Bangladesh fell slightly to 9.24 per cent in April, driven by a decline in food prices, although it still remains at an elevated level compared to historic trends, official figures showed yesterday.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) jumped to a seven-month high of 9.33 per cent in March, just behind the decade high of 9.52 per cent recorded in August.

Last month, food inflation declined 25 basis points to 8.84 per cent from the previous month's 9.09 per cent, while non-food inflation remained unchanged at 9.72 per cent, according to data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS).

Consumer prices have remained at an elevated level since July after the Russia-Ukraine war deepened the volatility in the global commodity markets, which had already experienced severe disruptions because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Ahsan H Mansur, executive director of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, said although inflation fell slightly, it is still higher.

"This means a persisting pressure on the lower- and middle-income groups."

"Anything (inflation) above 5 to 6 per cent is difficult for the common people to deal with whereas our inflation is still more than 9 per cent."

Mansur thinks inflation, in reality, is much higher than the figures released by the BBS. And the government is not taking any policy measures to fight inflation.

Anything (inflation) above 5 to 6 per cent is difficult for the common people to deal with whereas our inflation is still more than 9 per cent.

Since consumer prices started to go up because of the higher commodity costs globally and the adjustment of prices locally, one of the demands of local economists was to get rid of the 9 per cent interest rate cap on loans.

At the instruction of the government, the central bank has maintained the ceiling since April 2020 to keep the cost of funds low for entrepreneurs. But it emerged as an obstacle as the BB has not been able to squeeze the supply of cheap money despite raising policy rates four times since May.

"The transmission of monetary policy was impaired as a result of an ongoing interest rate cap of 9 per cent for the industrial sector lending," said the World Bank recently.

In January, the lending rate cap for consumers' credit was relaxed to vary up to 3 percentage points, allowing banks to impose an interest rate of up to 12 per cent. However, these categories represent only about 20 per cent of overall private sector credit.

And the WB said domestic financing of the deficit has increasingly been monetised, which is incompatible with inflation reduction objectives.

According to Mansur, Bangladesh is not being able to support the taka. "As a result, we are not being able to control inflation."

The taka has lost its value by about 25 per cent against the US dollar in the past one year, which made imports costlier.

Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the WB's Dhaka office, said the April inflation rate is not comparable with inflation rates in the past because of the differences in the base year and the basket.

"All we can say is that 9.24 per cent is still very high inflation. It has remained high in both urban and rural areas."

In rural areas, overall inflation fell 40 basis points to 8.92 per cent. Food inflation declined 28 basis points to 8.92 per cent and non-food inflation went down by 49 basis points to 9.33 per cent.

On the other hand, general inflation in urban areas rose 32 basis points to 9.68 per cent. Food inflation slipped four basis points to 9.10 per cent. But non-food inflation surged 37 basis points to 9.96 per cent, BBS data showed.

According to the BB, the inflation outlook might continue to confront some uncertainties in the second half of FY23 because of increasing price pressures emanating from the strained supply chain, pessimistic progress regarding a peaceful resolution of the war, and the elevated global commodity prices.

So, the central bank revised upwards its inflation target to 7.6 per cent from 5.6 per cent for the current fiscal year.

Hussain said the BBS has made significant methodological changes and most of these changes are in the right direction.

But some of these need more clarification, he said.

"For instance, why are they using expenditure weights from the 2016 survey and not from the 2022 survey whereas they are using 2022 prices as the base year prices? Why don't they provide a more meaningful breakdown of food inflation than just breaking it into just food and nonalcoholic beverages?"

"Macroeconomic policies need to remain vigilant to make sure they do not add fuel to the inflationary fire," said Hussain.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments