From piyaju to pizza: Dhaka’s street food business takes a delicious journey

Roughly two decades ago, Dhaka's street food scene was all about simplicity: crispy piyajus and singaras, deep-fried puris, or spicy jhal muri. Depending on the season, you would also find a variety of pithas -- comforting, traditional and closely tied to local flavours.

Back then, your elder brother or sister might have enjoyed a plate of chotpoti after school, but the idea of grabbing a cheesy pizza, a spicy plate of momos, or a juicy burger from a roadside cart would have seemed almost laughable. Because street food was then about what was familiar, what felt like home.

Fast forward to today, and Dhaka's streets tell a completely different story.

Over the past 20 years, hundreds of restaurants and thousands of roadside food carts have sprawled across the city. Now, you will find food carts in almost every alley -- run by young, educated and somewhat ambitious entrepreneurs who are reshaping the city's culinary landscape.

These vendors are not just selling food -- they are bringing global flavours to the streets, served with a side of innovation and affordability.

"Gen Z is not about impressing people by dining at fancy restaurants and spending a fortune," says Tasfia Sultana, 29, who dishes out unique creations like "Kebab-e-Burger" from her cart, "Grills on the Wheel".

"Restaurants come with all these extra costs -- service charges, VAT and whatnot. But we are here offering the same flavours at a fraction of the price, making it something everyone can enjoy."

These carts have become go-to spots for foodies, offering everything from Indian dosa, Nepalese momos, Pakistani chaap, and Turkish kebab, to Belgian-origin waffles.

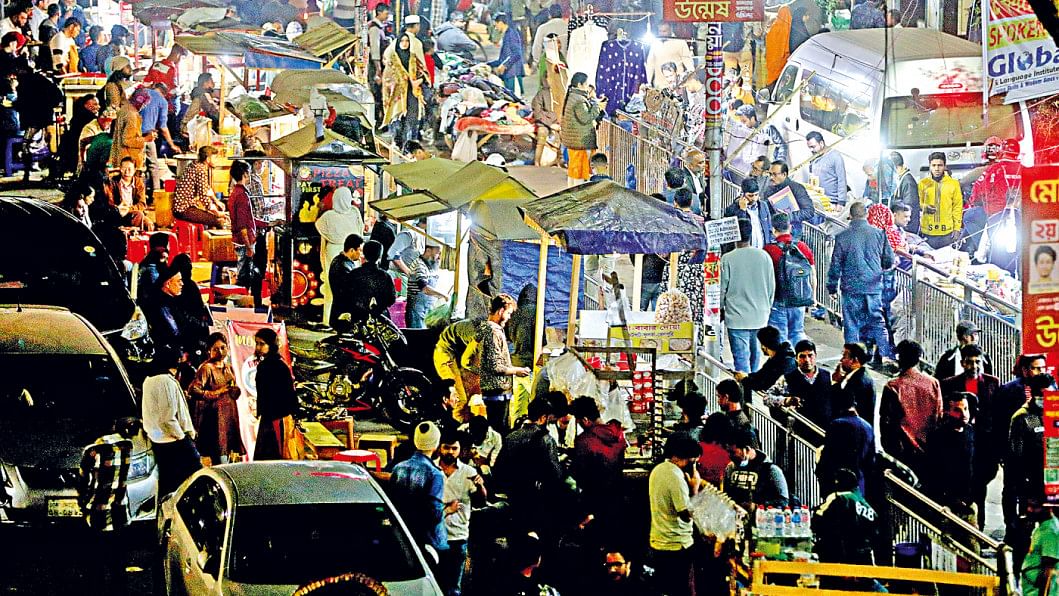

After sunset, local residents, young professionals, students and friends gather at these carts, often with minimal seating arrangements. They share food, chitchat, laugh and sometimes sing along to popular band songs under the open night sky -- "Cholo bodle jai..."

Interestingly, you still find old favourites like singara, puri and chotpoti, now sharing space with the newfound culinary offerings to Dhakaites.

THE RECIPE FOR CHANGE

So, what changed the food landscape of Dhaka in the past 20 years? The answer is simple: the internet.

As internet access became more widespread and access to smartphones increased, Dhaka's food scene began to change.

Young people, curious and tech-savvy, started exploring foods from around the world through social media platforms like YouTube and Facebook.

They watched videos of Japanese ramen, Indian dosas, Nepali momos and Turkish kebabs; and suddenly, the world felt a lot closer.

But it wasn't just the customers who were learning -- vendors were too. Through the same internet, they discovered recipes, cooking techniques and presentation styles from across the globe.

A street vendor in Dhaka could learn how to make momo or dosa almost in 10 minutes by watching a YouTube tutorial.

The result? A street food scene that is as diverse as it is delicious.

Local food vloggers also played a huge role in this transformation.

Food vloggers like Rafsan the Chotobhai, Adnan Faruque, or Syed Khaled Saifullah began showcasing Dhaka's street food to a wider audience.

Besides, international vloggers like Trevor James (The Food Ranger) and Sonny Side (Best Ever Food Review Show) visited the city, putting Dhaka's street food on the global map.

The internet did not just bring new recipes, it also created a community. Vendors and customers alike began sharing their experiences online, creating a buzz around street food that went beyond the streets themselves.

There were other factors, such as people's increasing disposable income, rapid urbanisation and many youths opting for entrepreneurship.

AFFORDABLE DELIGHTS

Faiyyas Hossain, a 16-year-old student residing in Dhanmondi, said, "I like having street foods like momo for their affordability. I can easily get one plate of momo comprising 5-6 pieces for Tk 100, while at a restaurant, it will cost at least double."

He also pointed out the wide variety of cuisines available at the roadside carts.

Hossain says he can pick between the spicy and tangy fuchka-chotpoti to a delicious pizza, often at the same spots like that at Dhanmondi 27, as it is more convenient.

Another customer, Sharifa Oishee, in the Dhaka University area, says, "From local snacks like chotpoti to foreign dishes, street vendors offer everything at a fraction of the price you would pay at a restaurant. It is not just convenient, it is also budget-friendly for us, especially with the rising cost of living."

However, Sharifa was a bit concerned about hygiene.

"While street food is a good option, vendors should focus more on cleanliness. Customers want to feel assured that the food they are eating is safe, so maintaining hygiene standards is crucial."

She said it would also be great if there were designated spots for street vendors, which would help reduce overcrowding and traffic problems.

According to Sharifa, proper seating arrangements and covered stalls could also make the experience more comfortable for customers.

Another customer, Fatima Rahman, who often brings her two kids to buy snacks from roadside food carts, said, "I prefer getting pizza from street vendors for my kids because it is affordable, and they love it."

"It is quick and convenient, and I know they will enjoy it just as much as the expensive restaurant versions," says Rahman.

EVERY FOOD CART HAS A DIFFERENT STORY

Food carts, sized roughly around 6x3 feet, have their own stories of emergence, struggle, operations and aspirations for the future.

Take Nahida Nowshin for example. At just 27, she runs "Waffle n'Momowali", a food cart in the Nakhalpara area of Dhaka.

After losing her mother, Nahida turned to cooking as a way to cope. "I remembered cooking with my mum," she says. "It became my way of keeping her memory alive."

Today, her cart serves waffles and momos, a unique fusion that has become a local favourite.

Nowshin now earns around Tk 30,000-35,000 monthly, with potential earnings reaching Tk 40,000 during peak seasons like winter.

Then there is Kamrul Hasan, a 30-year-old jobholder who started a food cart in Dhanmondi to supplement his income.

"I could not afford my expenses with just my salary," Hasan says.

His cart, which dispenses burgers, pizza, and sub sandwiches, is a hit among students looking for affordable snacks without hurting the wallet.

Hafizur Rahman, 27, represents a new wave of entrepreneurs who have started turning away from typical 9-to-5 jobs.

Rahman's cart, Addoon's Place, prepares burgers, meat boxes and momos.

"I started this because I wanted to build something of my own," he says. "When my business grows, I will quit my job and focus on this full-time," he says.

And let's not forget Azizul Islam, a 17-year-old who left school for personal issues but found an opportunity in street food.

"I saw that street food is affordable yet profitable," he says. "It is a business I can grow."

A GROWING INFORMAL SECTOR

On top of changing what people eat, Dhaka's street food scene is also reshaping the city's economy.

According to Khondaker Golam Moazzem, research director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), the street food industry is a significant contributor to the informal economy.

"This sector is creating employment opportunities, especially for young people," he says. "Right policies and access to finance are key to their continued success and growth."

Echoing similar views, Tapas Kumar Paul, assistant professor of economics at North South University, says, "Street food is more than a business; it is a reflection of our changing society."

"But without proper regulation, its growth could lead to chaos," he added.

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmmed, executive director at the Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies, also emphasised the potential for job creation. "This sector could provide opportunities for women and rural communities," he says. "It is not just about food -- it's about empowerment."

WHAT'S NEXT?

As Dhaka's street food scene continues to evolve, at least one thing is clear: things will not remain the same after the next 10 years.

Waffle n'Momowali's Nowshin hopes to expand her tiny venture by opening multiple stalls after 10 years. She wants to create job opportunities, especially for young girls.

Rahman, with his Addoon's Place, dreams about turning his cart into a full restaurant.

Meanwhile, vendors like Grills on the Wheel's Sultana put emphasis on maintaining high hygiene and food safety standards in upcoming years.

Her future target is to continue maintaining the use of fresh ingredients and keeping her stall clean to earn customer trust.

Economists say with the right support -- whether through training, financing or regulation -- this informal sector could become a formalised industry, creating jobs, boosting the economy, and preserving Dhaka's culinary heritage.

"The street food industry is already impacting the economy significantly," says Moazzem. "But to ensure its continued growth, we need to address challenges like licensing, hygiene, and access to finance."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments