Precision farming can raise yields by 25%

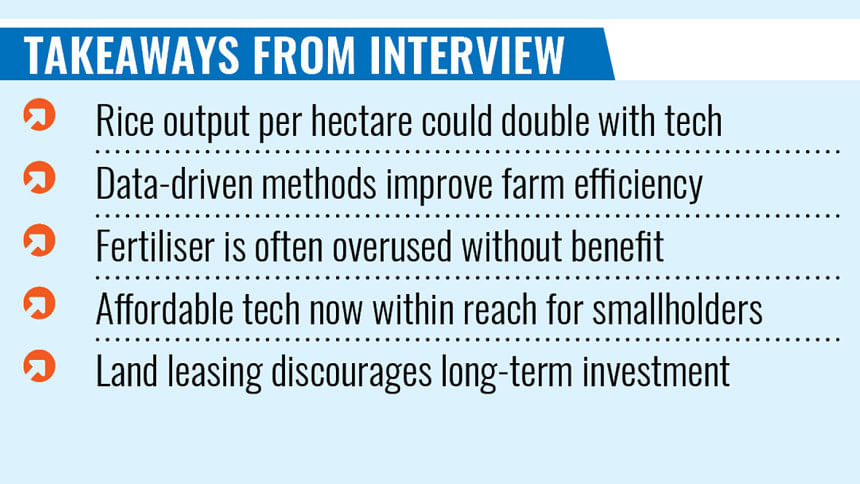

Bangladesh can boost crop yields by at least 25 percent through the adoption of modern technology in a cultivation method known as "precision agriculture", according to a Dutch environmental and soil scientist.

Precision agriculture, also known as precision farming or smart farming, is a modern approach to agriculture that uses data, technology, and targeted management to optimise crop production and reduce waste.

During an interview with The Daily Star recently, Prof Jetse Stoorvogel of the Department of Environmental Sciences at Open University in the Netherlands, explained that the approach involves collecting information about variables in crop fields, such as soil conditions, weather patterns, and crop health, and using this data to make informed decisions about resource applications and management.

The country is in a unique position where agricultural production continues to rise—unlike in many countries where growth has plateaued or declined, said the professor.

To sustain and optimise this progress, precision agriculture is essential in a country like Bangladesh, he added.

According to him, Bangladesh's current crop yields, especially in rice, are at just 50 percent of their potential.

"You're often producing 4 tonnes to 5 tonnes per hectare, whereas 10 tonnes could be possible," he pointed out.

Precision agriculture can help close that gap, he added.

If a field has low yield in one section, precision agriculture may help identify whether it needs more fertiliser, said Stoorvogel, who had visited Dhaka in the middle of July.

This approach allows farmers to use resources more efficiently, reduce costs, improve yields, and minimise environmental harm, he added.

It is particularly important for countries like Bangladesh, where food security is a challenge, the population is growing, and agriculture must become more resilient to climate change and market fluctuations, he said.

The scientist said Bangladesh has made some progress, particularly in developing seeds and adopting technological innovations, and that is the starting point of precision agriculture.

While the rest of the world has moved further ahead, Bangladesh still appears to be in the early stages of adopting precision methods, he added.

He said 25 years ago, a soil test cost $200. Today, handheld sensors go for around $100, and subscription-based advisory services on mobiles now make it possible to deliver real-time, customised advice to even the smallest farms, he said.

These tools, along with increasing access to machinery like combine harvesters and mobile-based advisory services, can make precision agriculture accessible to smallholders over time, he said.

In countries like Kenya and India, smallholders are already benefiting from such tools, and the same can happen in Bangladesh, with its growing access to smartphones and mechanisation bridging the knowledge and technology gap.

Another key issue is fertiliser overuse—many Bangladeshi farmers apply more than 300 kilogrammes per hectare, even when yields do not justify it, he said.

Based on soil conditions and crop performance, many farmers could safely reduce fertiliser use by 10 percent to 25 percent, cutting costs and improving environmental outcomes, he added.

He also said pesticides and herbicides must be applied at the right time, and that is where data and decision-support tools become invaluable.

Stoorvogel said a major concern in Bangladesh is the dominance of smallholder farmers, who often lack the resources to invest in advanced technologies.

In Bangladesh, a large portion of land is rented. Without ownership, farmers may be less inclined to invest in long-term soil health, he said.

He also said climate change is a big challenge for local farmers.

He emphasised addressing these issues step by step.

Private companies in Bangladesh could play a role in this transition by bundling advice, inputs, and even soil testing services, as has been done successfully in Uganda, Kenya, and Vietnam, he added.

They must coordinate across departments—seed, fertiliser, crop protection, and machinery—to offer integrated solutions, he said.

The potential is real, but success will depend on customised solutions, cooperation, and gradual, well-informed implementation.

Ultimately, government policies must support a strong ecosystem involving extension officers, farmers, researchers, and private companies. None can succeed alone, he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments