Why aren’t prices of essentials falling locally?

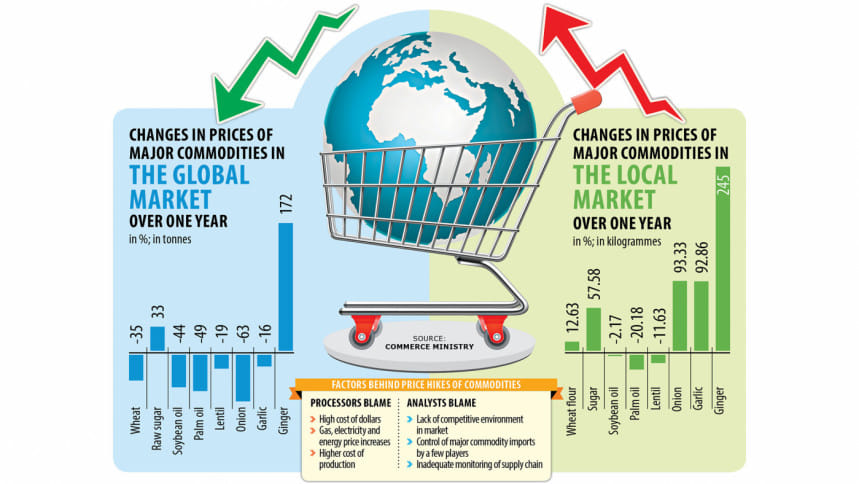

Global commodity prices are falling.

The Food Price Index of the Food and Agriculture Organisation also shows that the prices of commodities declined for the 13th consecutive month in May. The Index was 35.4 points, or 22.1 per cent, lower than the all-time high reached in March 2022.

The decline in May was underpinned by significant drops in the price indices for vegetable oils, cereals and dairy, which were partly counterbalanced by increases in the sugar and meat indices, said the UN agency in its latest prices index.

For millions of consumers in Bangladesh, things are, however, different. They are not reaping the benefit of the decline. Instead, they continue to see the opposite in some cases.

Take wheat flour, a highly import-based commodity. Over the last one year, the prices of the grain declined 35 per cent year-on-year to $311.5 per tonne in the international market.

In Bangladesh, the prices of wheat flour went up as much as 25 per cent during the same period, according to a commerce ministry paper presented at a meeting of the government task force on essentials yesterday.

The scenario is identical in the case of lentils.

The extent of price decline is much lower in Bangladesh than that of the global trend, raising questions about why prices are not falling locally in line with the international market.

For edible oil, consumers, however, have received some relief.

In the last one year to June 8, the prices of soybean oil have fallen 44 per cent to $912 per tonne in the international market.

Commodities processors cite various reasons, including the increased import cost because of the dearer US dollars and the hike in the prices of gas, electricity and energy. Some also blame the less-than-required imports of commodities such as wheat and the supply-demand mismatch.

Analysts also point to other issues, including a lack of competitive environment, control of major commodity imports by a few players, collusion among market participants, and a high profiteering tendency among businesses in the supply chain amid inadequate monitoring and enforcement by public agencies, compelling consumers to pay more.

In its review of the economy last month, the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) said importers argue that their current stocks were purchased at higher costs, preventing them from immediately lowering prices in response to a drop in global rates.

"If this argument is logical, then the reverse should also hold – when commodities are imported at cheaper prices, these should also be sold at lower prices until old stocks are depleted, even if there is a price hike in the international market."

"When international prices rise, importers immediately raise prices, even for their old stocks."

This is, according to the CPD, related to the presence of an imperfect market mechanism, where market rules fail to operate optimally. This has contributed to the current inflationary trend.

The CPD said high prices are not fully an external phenomenon.

Citing his experience, a top private banker dealing with international trade said a section of commodity importers do not want to cut the prices as they want to make up for their previous losses.

Asked, Md Shafiul Ather Taslim, director for finance and operation at TK Group, a commodity processor, blamed a surge in the cost of dollars as a key factor.

In January 2022, the dollar traded at Tk 84. It has now rocketed to Tk 110-Tk 111 amid a shortage of the American greenback.

"The cost of the US dollar has risen by 32 per cent," he said.

Electricity tariffs and transport costs have increased while gas bills have more than tripled in the last one year.

"So, how will the price fall in the international market affect the local market?" he questioned.

Businesses also blame the difficulty in opening letters of credit amid a shortage of US dollars.

Anup Kumar Saha, a top official of a commodity importing firm, says if the price in the global market falls, the price in the local market should come down theoretically.

"But the reality is that after importing a product and bringing it to the country, the price is determined based on its demand-supply."

"What happens in the local market is that when there is a gap in the supply-demand and the control of a product is in the hands of one or two traders, they monopolise."

Saha, who regularly follows the trends in the global commodity markets, says it is difficult to say when consumers in Bangladesh will start benefiting from the price reduction in the global market.

In a press release yesterday, Tapan Kanti Ghosh, senior commerce secretary, said wheat shortage stood at 24 lakh tonnes when it comes to requirement. In the case of sugar, the shortage was 72,000 tonnes.

The commerce ministry paper also mentioned an absence of proper competition in the market, a lack of records on the purchase and sales prices at the trader level, and weaknesses in policies in commodity market management.

In order to benefit consumers, it suggested the imposition of specific duties on essential commodities, expansion of market intervention by the Trading Corporation of Bangladesh, and giving priority to opening LCs by importers.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments