A governance assessment of lockdowns

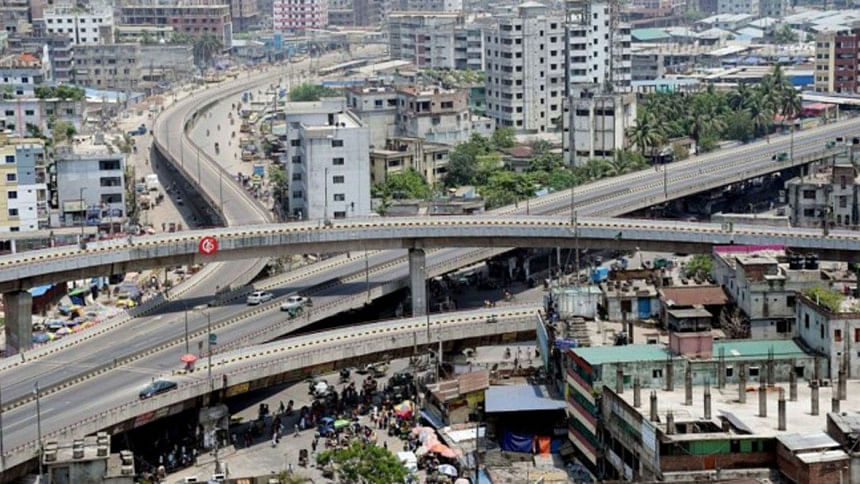

February 7, 2021 was a significant day for Bangladesh—logging only 292 new coronavirus cases in 24 hours, the lowest in almost ten months, it began its nationwide Covid-19 vaccination drive. However, the number of cases soon escalated, with the infection rate rising from three to seven percent between February and March. With the imminent lockdown following nationwide and district-based attempts at restrictions in past months, the government's handling of the second wave of the virus begs introspection.

Several factors influenced the initial upward trend in infections at the start of the year. First, the government was expecting a worse scenario of the infection rate during winter. When infections did not escalate, as anticipated, the people and the government became complacent enough to return to normalcy. Second, as the vaccination drive began, people began feeling safe enough to move around without following advised health protocols. Although only 50 lakh people were vaccinated by mid-March, less than four percent of the total population, it created a sense of safety among people. Third, people were desperate to come out of restrictions on movement and gathering. Moreover, the dilemma between public health safety and livelihoods escalated to people choosing livelihoods over health. Economic vulnerabilities became aggravated due to the combined effect of the government's lockdown and an ineffective and inadequate subsistence support system during the pandemic.

The government was relatively less vigilant in its approach during this year's rise in infections. According to a report by The Daily Star, the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), which has been collecting weekly data on areas at high risk of Covid-19, identified six districts with an increased risk of transmission on March 13. This grew to 29 districts on March 24. Bangladesh had 606 new cases on March 7; a month later, on April 7, it rose to 7,626, documenting the highest ever count in the country.

Similarly in India, after a declining rate of cases in the first week of March, a sudden surge took place in the following weeks. Throughout April and May, the world witnessed grim scenes of overwhelmed Indian hospitals, oxygen shortages, and deaths on the streets. On May 18, India reported the highest number of daily Covid-19 deaths ever recorded in any country worldwide.

Considering how the government was well-aware of the rising trend in infections in Bangladesh and the disastrous state of its neighbouring country, it should have started taking stronger measures earlier. Instead, it reacted the same way as last year and delayed imposing restrictions and a nationwide lockdown. Rather than acting early, the government began imposing restrictions with changing intensity as weeks went by. Around the end of March, the authorities put forth an 18-point directive, which consisted of restrictive measures to limit public gatherings, transportation and markets. Surprisingly, two days later, a lockdown from April 5 with a new 11-point directive was announced.

At the onset, the government seemed to apply some learnings from the past by being more decisive in identifying the type of institutions that must close, thus reducing confusion. Furthermore, stricter law enforcement was observed after the first week and up till the reopening of markets. However, when markets opened in accordance with government directives, people and shops were reported to be fined. The government also postponed all elections nationwide after announcing the new lockdown, unlike last time. Finally, it came up with some new ideas like the "movement pass" to aid citizens in need-based traveling.

However, these nationwide measures, despite some level of effectiveness, can be criticised as being inconsistent and coming too late. Initially, the nationwide restriction on public movement was announced for only a week, till April 11. A "strict lockdown" was announced in the next week and extended till April 28 with increasing intensity. The lockdown was extended six more times till June 16, arguably gradually losing its strictness, especially during the Eid holidays. Allowing businesses to revive throughout Ramadan and Eid festivities was a repeat of the first phase of the lockdown in 2020. Such repetition questions the government's farsightedness and learning. A longer lockdown extension was announced from June 16 till July 15, but with barely any serious enforcement as before.

The failure of the nationwide restrictions were followed by specific district-based restrictions. These were indeed essential, considering the spread of the new Delta variant of Covid-19. However, experts again criticised the restrictions for coming very late. The National Technical Advisory Committee on Covid-19 as well as local civil surgeons had advised immediate restrictions in seven districts in Khulna and Rajshahi divisions on May 31. As the virus quickly spread through these regions, enforcement became tougher. Presently, a nationwide "lockdown" has been announced.

Essentially, the overall response this year has not seemed well-planned and prudent. Repeatedly, experts identified specific, achievable, necessary guidelines implementable at the local level. Directives need to have a robust matrix, defined parameters and clear mandates. They also need to have specific measures based on precise data. Yet, the 11 directives given this April were ambiguous and difficult to implement. Some directives were broad and "asked" us to maintain such measures without clearly identifying the consequences of noncompliance. It is also difficult to imagine how they could be replicated on a small scale at the local level.

After the nationwide restrictions lost their aptness, district-based lockdowns seemed to be the dominant strategy. This was helpful for the economies of low-infection districts.

However, it seems that this strategy came too late as well, as the government has been forced to shift to a strict nationwide lockdown again. Most certainly, this will not be the end of lockdowns in this country. Therefore, the government needs a robust plan to keep the economy afloat while controlling the spread of the virus. In that case, commercial activities can only continue by restricting all unnecessary, recreational, public and social gatherings. Strict and targeted measures with heavy consequences for non-compliance can contain the virus from one side. Additionally, the government has to proceed with a clear plan and firm decisions.

The only practical lockdowns are the ones which have a broad relief plan and can protect healthcare systems from being overwhelmed. Even limited-scale lockdowns can only work as a measure for temporary control, not as a solution itself. In the long run, the only way out of such restrictive measures is a successful nationwide vaccination drive. Developed countries like the United States are returning to pre-Covid routines and vaccinated individuals are not required to wear masks in public anymore. European nations are also on their way to normalcy, with the current Uefa Euro 2020 football matches being played with supporters in the galleries. Only an immediate large-scale vaccination programme will ensure sustainable safety for the people of Bangladesh.

The nature and direction of this virus are still not fully traceable in terms of intensity and variety. Moreover, treating Covid-19 patients requires specialised medical arrangements like ICUs and oxygen. Therefore, we should ensure that we are prepared for the future and make a coordinated effort over the next couple of years to make necessary arrangements in terms of improving our health infrastructure. Based on current findings, a data-driven system can be established to track the nature of the virus, followed up with prompt actions by the government. Strict health and safety regulation compliance with preventive measures is a must. Finally, while large-scale lockdowns can only be a short-term strategy, considering their effect on vulnerable sections of the population, a large-scale vaccination drive should be the long-term focus.

Rafsanul Hoque and Insiya Khan are research associates at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), Brac University, and Mohammad Sirajul Islam is a programme manager at BIGD, Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments