Getting out of the middle growth rate trap

Many countries in the post-war era managed to reach middle-income status rapidly, but a few went on to become high-income economies, and several experienced a sharp slowdown in growth and productivity, falling into what has been referred to as the 'middle-income trap'.

Formal evidence on growth slowdowns and middle-income traps suggests that at a per capita income of about $16,700 in 2005 constant international prices, the growth rate of per capita gross domestic product (GDP) typically slows from 5.6 percent to 2.1 percent, or by an average of 3.5 percentage points.

Analysts observe that 85 percent of the slowdown in the output growth rate can be explained by a slowdown in the rate of total factor productivity growth -- much more than by any slowdown in physical capital accumulation.

Bangladesh today is on the cusp of graduating to a low-middle income status, with the per capita gross national income (GNI) nearing $1,100 in FY14, due to sustained growth, recent reforms in the national accounting methodology, and a rebasing from 1995/96 to 2005/06 (which increased annual nominal GDP by about 15 percent on average). In the decade ending 2013,

Bangladesh's growth appears to have been stuck at 6 percent. Now, 6 percent growth sustained over a decade is by no means a low growth rate. It is far above the average growth for developing countries and even middle-income countries over the past decade. But it is not as fast as growth in East Asia, Sri Lanka, or India during their formative growth periods. And this raises the question on whether Bangladesh is caught in a sub-optimal growth equilibrium -- a sort of 'middle-income growth rate trap'.

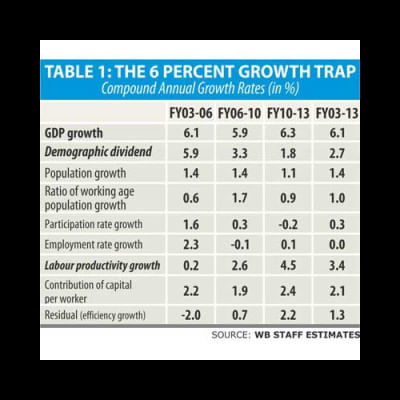

The trap is attributable to two opposing trends in Bangladesh's sources of growth. As the decomposition in Table 1 shows, labour productivity growth increased due to growth in capital per worker and efficiency growth. However, declining growth in the share of working age population and labour force participation rate reduced the demographic dividend. Note that since FY14, labour productivity growth also stumbled because of a stagnating private investment rate and disruptions in capacity utilisation.

Why should 6 percent growth, which is above the average for developing countries, be considered a trap, and so, a concern? Because this growth rate is significantly below what is needed for Bangladesh to comfortably be a middle-income country, with GNI per capita exceeding $2,000, by 2021. To achieve that target, the average annual GDP growth needs to exceed 8 percent per annum. This is why it is critical for Bangladesh to lift itself out of this middle growth rate trap. The question that remains is: how?

Bangladesh is well into the third phase of its demographic transition, as it has shifted from a high mortality-high fertility regime to a low mortality-decreasing fertility one. As shown in Table 1, the contribution of the demographic dividend to GDP growth shrank between 2003 and 2013. How can Bangladesh reinvent the demographic dividend? It cannot do so by increasing population growth -- this is neither desirable nor sustainable, given the already adverse balance between population and natural resources, particularly land.

Increasing the size of the working-age population is also not feasible, except perhaps by increasing the retirement age -- though that would be unlikely to make a noticeable difference. The employment rate, which is already 95.7 percent, has little room for further hikes. Bangladesh's problem is not a low employment rate; the problem is the abysmally low productivity of those employed.

To re-establish the demographic dividend, it seems that the only remaining option is to increase the labour force participation rate -- particularly for women. Female labour force participation (33.7 percent) has remained much lower than male participation (81.7 percent). Women account for most unpaid work, and are overrepresented in the low productivity informal sector and among the poor. Despite significant progress in recent decades, the labour markets remain divided along gender lines, and progress toward gender equality seems to have stalled.

Raising the female labour force participation rate by easing labour market entry barriers for women is a practical necessity for Bangladesh now.

Higher female labour force participation can boost growth by mitigating the impact of a shrinking workforce growth rate. Table 2 shows the impact on potential GDP growth rates under three different assumptions about the female labour participation rates (FLPR).

If the FLPR rises by 2.5 million a year, the participation rate will equal the current rate of male participation (82 percent) in Bangladesh in ten years. This will add 1.8 percentage points to potential GDP growth each year, taking it to 7.5 percent -- the minimum rate needed to be in a comfortable middle income zone by 2021.

Less ambitiously, if it rises to 48 percent in ten years, reaching the level of Japan in 1990, the potential growth rate rises to 6.5 percent, as 0.75 million female workers are added to the labour force each year. Somewhere between these two, if it rises to 75 percent in ten years, reaching the level of Thailand in 1990, the potential growth rate rises to 7.3 percent, as 2.1 million additional female workers are added to the labour force each year.

How will Bangladesh's labour market absorb such large increases in new entrants to the labour force? Increasing investment will tackle the challenge of providing employment to an additional 2.5 million additional women every year. Based on the estimate of capital per worker in FY13, the stock of capital will need to grow at 4.3 percent a year to accommodate the additional 2.5 million female entrants domestically. To be sure, such high investment aspirations cannot be reached in their entirety in the immediate future. But the doors can be cracked open, starting now.

The composition of investment also matters for female participation. Investment in infrastructure and transportation services reduces the costs related to work outside the home. In rural Bangladesh, upgrading and expanding the road network increases labour supply and incomes. Access to electricity and water sources closer to home frees up women's time for work and allows them to integrate into the formal economy.

In rural South Africa, electrification was found to have increased women's labour market participation by 9 percent. Better access to information and communication technologies can facilitate access to markets and market work. More generally, investment needs to rise significantly to support creation of employment opportunities for both women and men.

It is important to take into account gender differences in assessing the sources of economic growth and in designing interventions to increase female access to labour, credit, and product market changes. There is a simultaneous relationship between gender inequalities and economic growth. Gender inequalities reduce economic growth, while at the same time, economic growth leads to lower gender disparities. Supporting the reconciliation of work and family life increases female labour participation.

Analytical assessments on what works for women in Bangladesh show: (i) a 10 percent rise in average years of schooling of female adults increases female labour force participation by 8.5 percent; (ii) a 10 percent fall in average household size increases FLFP by 10.04 percent; (iii) a 10 percent rise in the coverage of social protection (share of income from SP in total income of the recipient) increases FLFP by 0.82 percent; and (iv) women's agency rises through participation in micro-credit programmes and employment in the garment industry.

The policy response to women's employment has been largely through anti-poverty programmes such as safety nets, social protection initiatives, small livelihoods programmes, micro-credit, and so on. Much more attention is needed to macroeconomic policy linkages. It is true that the leverage needed to stimulate women's participation and employment is mostly on the public expenditure side -- primary education, tertiary education, technical training, provisioning of early childhood education and day care programmes, improving feeder roads, storage and distribution facilities and gender sensitising extension services and marketing information. It is also true that restrictions on women's rights to inheritance and property and legal/social impediments to freely pursuing a profession are strongly associated with large gender gaps in labour force participation. It is time to address these barriers.

Transformation in the size and structure of female employment is an integral part of Bangladesh's quest for increasing aggregate total factor productivity (TFP). Increasing TFP is the surest way to get out of the 6 percent middle growth rate trap.

The author is lead economist, World Bank Dhaka office.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments