Back to square one

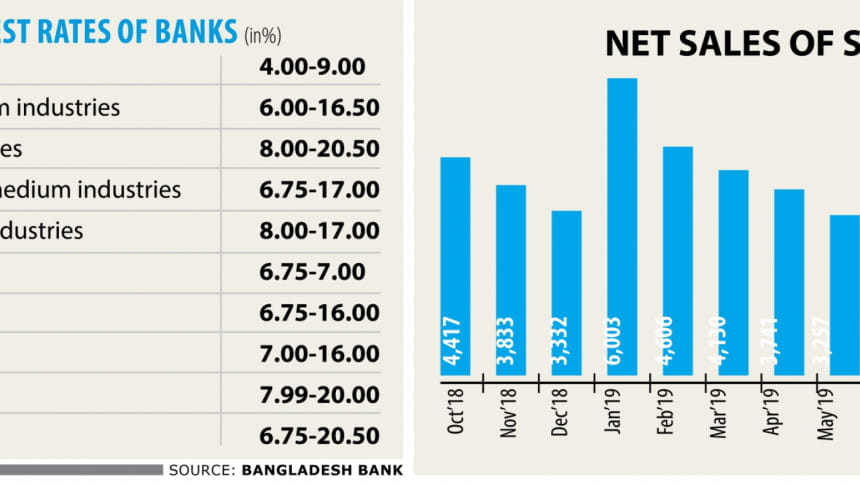

It’s deja vu all over again. On June 21, 2018, Bangladesh Association of Bankers (BAB), a platform of private banks’ owners, agreed to cap the interest rate on deposits at 6 percent and the lending rate at 9 percent from July 1, 2018. This did not work despite significant monetary and fiscal policy support. Other than continued weakening of the financial health of the sector, not much has changed a year and a half later except that the BAB has once again announced bringing lending rates down to 9 percent with deposit rates capped at 6 from April 1, 2020. Back to square 1 after a Bangladesh Bank (BB) committee spent days to recommend capping lending rates at 9 percent for “industrial/manufacturing” sectors only while leaving other lending rates and all deposit rates free for the market to set on a commercial basis.

The headwinds that curtail the possibilities for investment and growth in Bangladesh are well known. In the banking sector, most of the headwinds are our own making. What is different this time that could make us believe that the same old wine in the same old bottle would taste better? Hard to figure except, according to BAB, there is fuller government support! This is a new known unknown because “no additional support will be required for banks for implementation of the decision”, according to BAB again. What does “fuller support” mean then? You get a hint from the Finance Minister: “government will provide support to banks for a while” to tide over losses caused by the lower lending rate. Exactly half of state-owned entities deposits have to be held in private banks at 6 percent.

Whether shopping for business or housing loans, borrowers are naturally concerned about rates and terms to make sure they do not pay too much for the use of someone else’s money. It is therefore no surprise to see business leaders wasting no time to welcome the move and even seek preponement of its implementation.

What is the economic case for ceilings on interest rates? Do ceilings always result in lower rates without reducing the amount of available credit? Do some borrowers tend to benefit from ceilings more than others?

The argument justifying the 9 percent cap is that high interest rates are driven by substantial risk premia on loans. Lenders calculate the risk premium based on the probability that a borrower repays the loan and the loss in case of default. It is difficult to accurately assess these parameters due to lack of information on firms or households with no or little credit history and recoverable collateral. Unable to identify a borrower’s potential for repayment, banks charge an interest rate which is more attractive to the higher risk client. This feeds back into higher risk premia and lending rates. The problem is particularly acute when banks lack proper tools to price and manage risks efficiently. Moral hazard occurs when clients borrowing at this high rate make riskier investments to cover their borrowing costs. This also increases default probabilities and risk premia.

Caps on interest rates might alleviate this vicious cycle by altering the interest rates that would otherwise be charged, making them also attractive for more credit worthy borrowers and reducing the pressure to engage in high risk projects to cover the borrowing costs.

On the surface, this seems logical. However, there is more to it than meets the eye, particularly the unintended consequences which can undo in practice what appears impeccable in theory.

When a ceiling is introduced, it may have no impact on the credit market, or it may alter the way in which the cost and quantity of credit are determined. Exactly what happens depends on where the ceiling is relative to the initial market rate. When the ceiling is above the market rate of interest, it has no effect at all. When the ceiling is below the market rate of interest, as is the case in Bangladesh now, it can affect the market outcome in many different ways.

A ceiling below the market rate is binding if enforcement is perfect. When binding, the ceiling rate becomes the rate of interest charged. But it may also decrease the quantity of credit supplied. Like any other business, if a lender does not recoup its costs and earn an adequate return on its resources, it will put those resources to work elsewhere. Since the amount of credit offered at the ceiling rate will not satisfy all those who are willing to borrow at the 9 percent rate, excess demand is created, giving rise to a situation in which the reduced amount of credit must be rationed among borrowers by some means other than the ceiling rate.

Bankers may set rigid loan terms, screen borrowers more rigorously, increase non-interest fees and charges, or concentrate the impact of ceilings on certain borrowers. Imposing more stringent loan terms such as shorter maturities and higher minimum loan size reallocates credit toward those who are able to afford larger down payments or larger monthly payments. While a ceiling may reduce the explicit interest rate, it may not result in lower overall costs of borrowing even for those able to obtain loans. Several studies internationally on the effects of restrictive interest rate ceilings have established that loan terms do become less favourable to borrowers. No matter how elaborate the monitoring mechanism may be, banks have little difficulty demonstrating ceiling compliance to the regulator using creative accounting.

Basing lending decisions heavily on individual characteristics, such as borrowing history or income, without the flexibility of adding risk premiums, can ration credit away from new borrowers who might be willing to pay higher than 9 percent. Low priced credit is not useful to those who cannot meet the requirements for obtaining it. Usually, when lenders ration credit by some means other than interest rates, first-time borrowers, small borrowers, low-income and high-risk borrowers find it more difficult to obtain credit. The creditworthy borrowers, on the other hand, may obtain more credit than they would have at normal market interest rates.

The willingness to provide credit at the ceiling rate depends also on the cost of funds and the prevailing “risk-free rate” in the economy.

To reduce costs of funds we have 6 percent cap on deposit rates and to ensure fund availability to the private commercial banks (PCB) we have 50 percent government deposit requirement. Shifting government deposit from state-owned banks to the PCBs is a zero-sum game for the banking system as a whole. It does not increase the total funds available to the banking system. It is not clear how much the PCBs will benefit since the average deposit rate is below 6 percent currently as remittances have boomed and the net sales of the National Saving Certificates has declined significantly. The deposit rate ceiling does not make a difference to bankers when they are getting deposits at a lower rate any way. The 6 percent cap, if binding, may hurt depositors who have no other option but to keep their money in the bank.

Risk free lending options to bankers have become attractive recently. Between July 2018 to November 2019, risk free rates have increased by at least 3 percentage points, with rates on 5-year BGTB approaching 9 percent and 10-year BGTB above 9 percent. If the government is offering risk free lending opportunity to the bankers at close to or even above 9 percent, why would bankers be interested to lend heavily to risky borrowers at 9 percent?

Political economy consequences are important too. A combination of the presence of state-owned banks and interest rate controls can turn into a mechanism for ensuring that cheap credit flows only to specific borrowers. Unconnected and small firms may get very little benefit from the policy. As a result, the bottom tier of borrowers could lose access to credit. The sustainability of growth and inclusion may then be seriously jeopardized by lowering economic efficiency if credit worthy borrowers with no elite connection are excluded.

These practices may erode the benefits that the 9 percent cap aims to provide. Since the intended policy goal is to reduce the overall cost of credit in the economy, the solutions should be based on the causes of the “excessive” rates.

As argued earlier, the main reason for high interest rates is large default risk premia. This can be reduced by more efficient loan foreclosure procedures, including the small claim procedures, summary procedures for uncontested debt, alternative dispute resolution mechanisms that allow banks to limit the losses stemming from default of the borrower and plugging legal loopholes in the enforcement of insolvency procedures.

Risk premia can also be lowered by enabling choice of the appropriate lending technology. The latter is a combination of primary information source, screening and underwriting policies, loan contract structure, and monitoring mechanisms.

Another pressure on commercial and industrial lending rates currently is large government borrowing at high rates. Together with taka liquidity drained by foreign exchange market interventions, shallow domestic debt markets and limited access to global debt finance, this limits the availability of loanable funds for the private sector. Remediation requires a prudent fiscal and debt management framework, greater exchange rate flexibility, reforming administered interest rates and capital market development.

The author is an economist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments