In Bangladesh Bank we trust

This ought to be, if it already is not, the motto of stock market players in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Bank (BB) has left no stone unturned to show that it stands ready to put lipstick on everything to drive stock markets higher.

In the process, it has seen how hard it is to make lipstick stick. So far there has been no free lunch. As they say, failure is the pillar of success, so keep trying.

The BB has now opened another window to encourage banks to invest in the stock market.

Each bank can create a special fund worth Tk 200 crore for five years to expand their exposure to the stock market subject to several regulations.

The banks can use their own funds or borrow from the BB at 5 per cent, instead of the existing 6 per cent, for 5 years through repo or refinancing mechanism against treasury bills and bonds.

Banks had Tk 1.4 lakh crore in bills and bonds as on June 29, 2020, thanks to the surge in government borrowing from the banking system during the last year and a half.

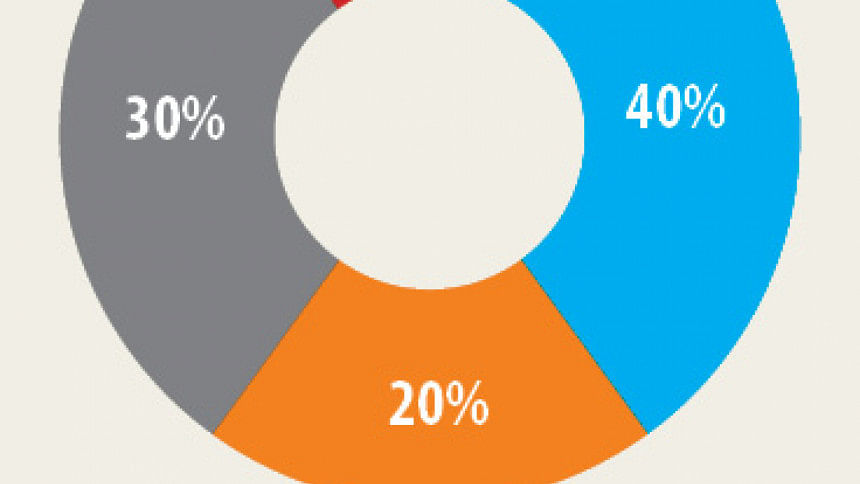

The banks can invest the fund directly to build their own new portfolio (40 per cent), new portfolio of their subsidiaries (20 per cent), other bank or their subsidiaries (30 per cent) and other merchant bank or brokerage houses (10 per cent).

They also have the option to lend to share market intermediaries at 7 per cent rate of interest without needing to include it in their loan-deposit ratio.

Remember, the ratio is not allowed to exceed 85 per cent for conventional scheduled banks. The BB will closely monitor the use of this fund on a quarterly basis.

The total liquidity in the banking system will be about Tk 11,400 crore higher if all the 57 banks use the repo facility to create the fund. This could potentially increase reserve money (BB's holding of net foreign assets, claims on government and claims on deposit money banks) growth by 4.5 per cent (relative to the stock at end-December 2019) by increasing BB's claims on the banks.

It will therefore be fair to characterise this as a step towards monetary expansion. However, the link between reserve and broad money (net foreign plus domestic assets of the banking system) growth has been rather variable in recent years.

Banks have been very reluctant to invest in the stock market since 2016 as slumping stock prices eroded profit from portfolio investments.

While initiatives like this are designed to help keep liquidity flowing to the bourses, the latest measures could push up banking sector risk if they lead banks to buy higher risk shares than they previously had appetite for.

The banks' overexposure to stock market contributed to creating stock price bubbles in 2010, leading BB to tighten regulations on banks portfolio investments.

Times have changed. BB offered liquidity support to banks in September last year at 6 per cent repo rate to nudge banks to invest in shares. Hardly any bank responded to the Tk 3,000 crore opportunity because the profit prospects were extremely poor.

Even before the advent of the coronavirus, the state of the economy was weak. Many big corporates listed in the two stock exchanges have suffered declines in sales and profit in the first half of the current fiscal year.

Confidence on the governance of the stock exchanges and regulatory institutions does not appear to have improved.

The spread of coronavirus has dampened expectations about a recovery in export, import and credit growth in the second half of the current fiscal year.

Vastly increased government borrowing from the banking system and the consequent rise in the risk-free rates has reduced the incentive for banks to look for alternative income earning opportunities.

Whether the 1 per cent reduction in the repo rate to borrow for investing directly or indirectly in shares will be sufficient to overcome the pre-exiting deterrents is literally a 11,400-crore-taka question.

It will not at all be surprising to see the market rise in the next few days on the expectation of fresh liquidity injection from the banks.

However, such increases could quickly revert back to bearish trends since the bullish outlook is not driven by any change in the market fundamentals. Banks therefore run the risk of losing their investment as expectations of price rise induced by the latest announcement fizzle out. Historically, unlike in developed country markets, returns to stocks have failed even to stay ahead of inflation. In fact, if you invested in the whole basket on which DSE Index is based, you would have suffered a capital loss at a compound annual rate of 5.2 percent since 2010. Thus, holding on to investments in shares does not offer much promise.

There is considerable debate on the appropriate role of stock prices in the determination of monetary policy.

Conventional wisdom says changes in stock prices should affect monetary policy only to the extent that they affect the central banks' assessment of capital accumulation.

Bangladesh's overarching approach across the financial system is aimed at achieving a more inclusive financial system in which banks can support lending to parts of the economy that are beyond their risk appetite; the micro, cottage and small enterprises for instance.

The stock market does not fall in this category because such enterprises are not listed in the bourses.

Exposure to stock market, on the other hand, increases the potential of risks spilling over to banks, exacerbated by the limited capacity of Bangladesh's capital market regulator to provide comfort on improved governance.

The recent stock market bust has created a serious dilemma for BB. Shares are trading at prices that seem well below normal as is the volume of trading. However, it is hard to figure the "normal levels".

We can almost never be sure whether these reflect a demand supply mismatch or simply a re-evaluation of fundamental values by market participants. These two different interpretations have very different implications for the appropriateness of BB actions. aking the problem worse is the fact that the markets are influenced by several other factors.

There are good reasons to worry about attempts by BB to influence stock prices, including the fact that the effects of such attempts on capital market psychology are predictably unpredictable.

Effective market discipline requires credibility. Aggressive banks responding to the new policy initiative must believe that they are at risk of loss and that there is no insurance backing them up.

It is neither possible nor necessarily wise to eliminate entirely the potential for support of uninsured banks.

However, it is possible to reduce both the probability of a bailout and the extent of protection banks receive when a bailout occurs. This can partially mitigate the moral hazard associated with the public safety net supporting banking.

Putting responsive banks at risk of loss in a credible manner is no easy task. Experience tells us that such credibility needs to be explicitly established.

We cannot count on banks to spontaneously decide to price risk appropriately. A mechanism to limit spill overs from one bank to another is critical because these spill overs -- the contagion effect -- are a principal rationale for bailing out the aggressive banks when all their stock market bets fail and they each end up owing Tk 200 crore to the BB.

The author is an economist

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments