BTRC’s new policy seeks to cut red tape

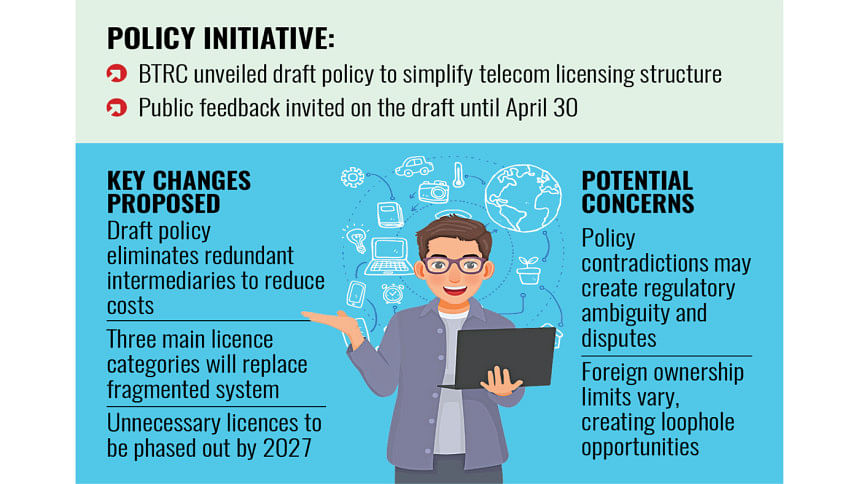

The Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) has unveiled a draft policy aimed at overhauling the telecommunications licensing and regulatory framework, although a lack of clarity in certain areas may lead to disputes over service boundaries.

Titled the "Telecommunication Network & Licensing Regime Reform Policy 2025", the draft proposes the elimination of several minor intermediaries -- introduced under the controversial previous policy -- that not only increased operational burdens but also raised compliance costs.

The BTRC released the draft on Tuesday and has invited feedback from stakeholders, experts, and the general public by April 30.

At the heart of the reform is the consolidation of the fragmented licensing structure into three main categories: National Infrastructure & Connectivity Service Provider, International Connectivity Service Provider (ICSP), and Access Network Service Provider.

Currently, there are over 20 types of licences in Bangladesh's telecommunications sector.

Bandwidth for internet services comes via submarine and international terrestrial cables. It is distributed through International Internet Gateways (IIGs) to mobile and broadband providers.

Fibre transmission is managed by Nationwide Telecommunication Transmission Network operators, while tower companies handle mobile base transceiver station installations.

Voice calls between operators are routed through Interconnection Exchanges (ICXs), and ISP data through the National Internet Exchange (NIX). International voice calls pass through a separate layer called the International Gateway (IGW).

The ANSP licence will consolidate mobile and fixed-line services into two sub-categories: Cellular Mobile Service for operators using technologies like GSM, 5G, and future evolutions, and Fixed Telecom Service for wired or wireless broadband providers.

ANSP licensees will manage last-mile connectivity, offer bundled voice, data, and digital services, and share passive infrastructure such as towers and fibre, though spectrum sharing will require BTRC approval.

Existing mobile operators, ISPs, and Public Switched Telephone Network providers will migrate to these categories, with fixed-line operators barred from holding mobile licences to prevent market dominance.

The NICSP licence will focus on building and leasing nationwide telecom infrastructure, including optical fibre networks, towers, and transmission facilities, to ANSPs.

This aims to reduce redundant investments, lower operational costs, and ensure connectivity reaches rural areas up to the union level.

The ICSP licence will unify international connectivity services, replacing legacy permits such as submarine cable and IGW licences.

ICSPs will manage submarine cables, terrestrial links, IP transit, and carrier contracts.

This shift aims to optimise underutilised submarine cable capacity and reduce reliance on foreign digital infrastructure.

Alongside these licences, the policy introduces lighter regulatory frameworks for small-scale operators.

Small ISP service enlistment will allow upazila/thana-level internet providers to operate under the oversight of Fixed Telecom Licensees or ICSPs, while Small Telecom Service enlistment will enable niche providers, such as SMS aggregators and enterprise solution vendors, to enter the market with minimal bureaucratic hurdles.

The policy also phases out obsolete licences by 2027, including IGW, ICX, and NIX, citing their inefficiency in a converged technological landscape.

Operators under these categories must transition to the new licensing regime or cease operations upon licence expiry.

Call centres, TVAS, and vehicle tracking services will be deregulated entirely, while VSAT providers will shift to a softer enlistment framework, reducing barriers for startups and SMEs.

Contradiction and lack of clarity

However, there are a number of contradictions and areas of confusion within the policy.

For instance, while mobile operators are permitted to provide enterprise services using both wireless and wired technologies, elsewhere the policy restricts them from obtaining licences typically required for offering wired services.

"In one sub-clause of the policy, the capabilities of mobile operators are expanded to include wired services, while in another, they are explicitly restricted from providing them. This creates regulatory ambiguity and could lead to disputes over the boundaries of permitted services," said Abu Nazam M Tanveer Hossain, a telecom policy expert.

Similarly, the policy both calls for strict separation between different types of service providers and, at the same time, allows foreign investors to hold stakes across multiple categories.

"Without clearer guidance, this could lead to regulatory loopholes and conflicts."

There is also inconsistency in how foreign ownership limits are applied. Some licence types have lower caps than others, and some don't mention any restrictions at all.

"This opens the door for companies to exploit these differences by choosing licence categories that best serve their investment interests, regardless of actual service alignment,"

While the policy acknowledges the importance of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), it does not include any regulatory or licensing framework for them.

"This creates uncertainty and could lead to uneven application of the policy."

Three-stage migration roadmap

A three-stage migration roadmap will guide the transition to the new policy.

Stage one will be implemented in 2025 and will focus on policy enactment and regulatory adjustments to encourage industry consolidation.

Stage two will introduce new licences, allowing existing operators to migrate voluntarily by 2026 and stage three will mark full implementation, with all legacy licences phased out by 2027.

The BTRC emphasised that the transition will prioritise service continuity, fair competition, and efficient resource utilisation, particularly for infrastructure like fibre and data centres.

The policy mandates strict quality of service standards, tying compliance to licence renewals.

Infrastructure sharing -- such as towers, fibre networks, and data centres -- is strongly encouraged to cut costs and avoid duplication.

Satellite and Non-Geostationary Orbit (NGSO) operators, classified under a special Fixed Telecom License category, will operate under tailored rules for spectrum allocation and cross-border connectivity.

Shahed Alam, chief corporate and regulatory officer at Robi Axiata, said, "We welcome the draft for the reform of the telecommunications network and licensing framework. The proposed licensing framework is expected to bring the desired discipline in this sector.

"However, we have some scepticism about the role of this policy in improving the quality of the network and reducing the cost of services as the draft mainly focuses on reducing the number of licences. We are hopeful that BTRC will encourage mergers and acquisitions in NICSP layer to ensure affordable services for customers and create new investment opportunities for mobile operators to increase competition in the market."

The proposal to further deregulate several sectors of the telecommunications ecosystem is also commendable, he added.

Rakibul Hasan, a former BTRC director and chief technology officer of Link3 Technologies Limited, praised the regulator's recent efforts to revise its international long-distance telecommunication services (ILDTS) policy.

He said that the outline BTRC has created now follows global standards.

"In Bangladesh, there are many types of licences and managing them is difficult. To improve services in the telecom sector from a global perspective, we need to encourage mergers or acquisitions. This will help increase foreign investment and improve the government's ability to manage the sector," he said.

He also mentioned that there should not be too many rules for modern digital service providers. Instead, joint ventures should be encouraged, and some policies should be left to the market.

"In the end, service quality will improve, customers will benefit, and the market will grow. It's all about scale."

He pointed to an area of ambiguity, saying that "access" and "transmission" should be clearly defined for service providers.

"Otherwise, others are entering the ISP market without following licensing clauses. Also, in the enterprise sector, fixed and wireless services should be operated separately."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments