How property taxes can help low-income countries to develop

The world's governments must raise an additional $3 trillion to achieve sustainable and inclusive economic growth goals this decade. The cost in emerging markets equals 4 percent of gross domestic product—and 16 percent for low-income countries.

How can countries finance such staggering price tags? Large cities such as Delhi and Lagos show a way forward: Taxing property more efficiently can play a meaningful role in raising revenue at the local level, allowing countries to invest more in their people, new IMF analysis shows. Previous IMF research has shown that countries have ample potential to raise more domestic tax revenue if they need it—up to 5 percentage points of GDP over two decades.

Of course, the political challenges of such reforms are far from trivial, as recent events in several countries suggest that raising taxes can create social unrest. More efficient real estate taxes have an advantage in this regard: by being locally collected and spent, they may be politically less challenging than increases in broad-base national taxes.

Recurrent taxes on immovable property could help local governments capture the wealth generated through construction-intensive urbanization. Generating such revenue fairly is especially important given the difficulty in developing countries of taxing income and wealth, which can be highly mobile.

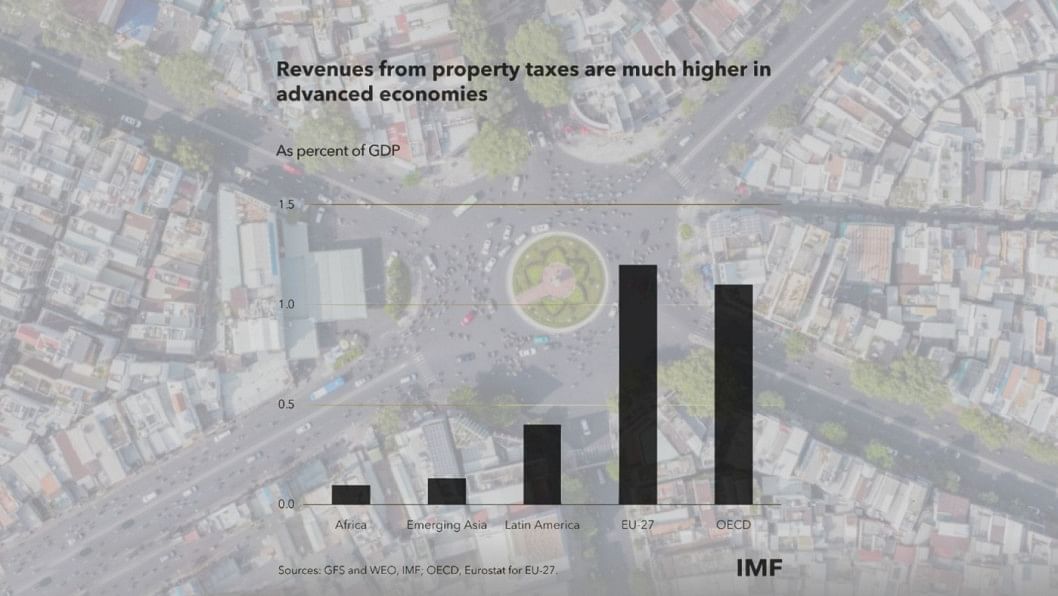

The appeal of property taxes is clear when we look at revenue raised in advanced economies: more than 1 percent of GDP on average in OECD countries, and nearly 3 percent in some advanced economies. By contrast, they raise only around 0.1 percent of GDP in emerging Asia and Africa.

Achieving such a large growth requires improving property-tax coverage and addressing the capacity challenges in valuing real estate as ways to reverse the current revenue underperformance. New property identification technologies and simplified valuation methods have become widely available. With policy reforms and better technology, recurrent property tax revenues in developing countries should be at least 10 times higher than current levels.

Local revenue and spending

When well designed, property taxes become a reliable and progressive form of municipal financing. They enhance the accountability of local governments, since proceeds can be used to fund better local public services, and taxes the increase in wealth of those who own real estate that has appreciated due to urbanization and associated public-infrastructure development. The tight link at the local level between revenue and spending shields property taxes from national politics and imposes higher accountability standards on local councils for the effective use of the resources.

National legislation should regulate how much property taxes can differ across a country, limiting divergences in the level of local public services funded by this source. Municipalities should limit exemptions to a narrow range of public organizations, and forgone revenues should be regularly reported.

The impact on "asset-rich but cash-poor" households such as pensioners can be softened by deferring taxes until the property is sold, at which point full payment is due.

Satellites and drones

It's best to take a gradual approach to property-tax reform, using modern technology to broaden the coverage of area-based taxes (expressed as a fixed rate per square meter). The goal should be to transition to full value-based property taxes in coming years as countries gain experience in implementation and market price information is meticulously recorded for periodic property valuation.

Modern mapping technology, such as satellite imagery and aerial photography by drones, can be used to fast-track the expansion and coverage of property taxes to all parcels that ought to be included in the fiscal register.

Indian officials in Delhi and the greater Bangalore metropolitan area have started using satellite imagery to map properties in a geographic information system. In Africa, several municipalities have made impressive strides. Lagos increased tax collection fivefold to more than $1 billion in 2011 by broadening the base of its property tax, coupled with better enforcement.

The increased precision of satellite images enables the accurate measuring of surface areas and the development of fiscal-register maps that depict buildings and their alterations. This allows the fast roll-out of an area-based property tax until valuation capacity has advanced to migrate toward a market value-based property-tax system that can raise more revenue.

Demand for capacity development from the IMF in this area indicates that many countries are seeing the benefits from this combination of the right policies and technology enablers. It makes property-tax reform effective and politically appealing, especially when its objectives are communicated properly to the public.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments