How regulatory hurdles keep internet price high and speed low

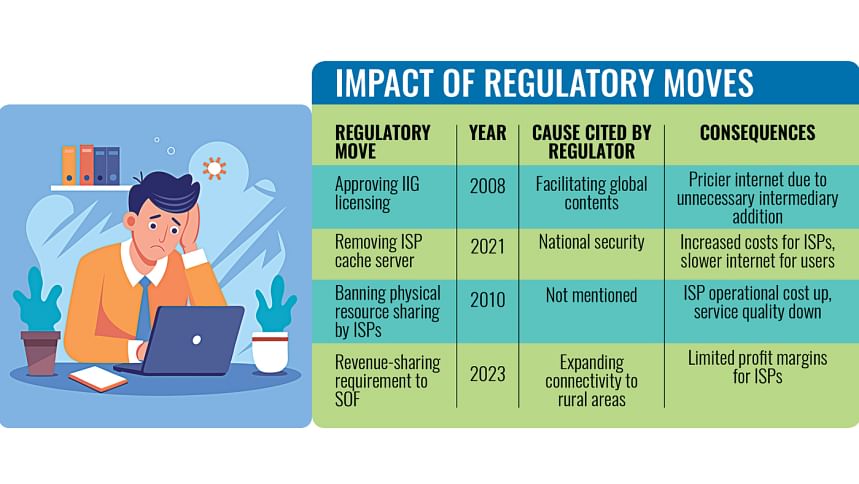

The Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) has implemented a number of policies over the past 16 years that, according to internet service providers and users, have made Bangladesh pay higher prices for slower internet speeds compared to its neighbours.

With those moves, they say the BTRC has turned into a "money-making machine for the government" rather than a facilitator of connectivity.

Take the BTRC's 2021 order to remove cache servers from small and medium sized internet service providers (ISPs) for example.

That meant ISPs were not allowed to store content locally, forcing users to travel longer distances to access it.

Consequently, ISPs incur increased costs and internet users experience slower speeds, according to industry insiders and experts.

"Globally, cache servers are managed by last-mile service providers to ensure quick access to content for users," said Md Emdadul Hoque, president of the Internet Service Providers Association of Bangladesh (ISPAB).

Industry insiders claim that ISPs have to pay an additional Tk 80 to Tk 120 per Mbps of internet compared to mobile operators due to these rules. This disparity puts ISPs, especially in rural areas, at a competitive disadvantage

"Now we pay Tk 25-60 per Mbps for this service. This has added an unnecessary layer of costs and impacts the quality of service."

Without discussing the nitty-gritty, global internet supply broadly passes through several stages to reach households and offices.

It first reaches Bangladesh via submarine or terrestrial cables at landing stations.

International Internet Gateways (IIGs) then handle the data, passing it to the National Telecommunication Transmission Network (NTTN), which distributes it across the country.

ISPs deliver internet directly to homes and businesses through local distribution networks, while mobile network operators (MNOs) receive internet from the IIGs.

However, both MNOs and broadband service providers claim that the IIG layer is unnecessary and that they could directly obtain supply from the NTTN.

In 2008, the BTRC granted the first private IIG licence. Taimur Rahman, chief corporate and regulatory affairs officer at Banglalink, said: "It is another layer that does not add any value."

The BTRC also imposed restrictions on ISPs, prohibiting them from sharing physical resources like fibre-optic cables and active network equipment such as switches, routers and optical line terminals.

In simple terms, if an ISP leases 1 Gbps of capacity from the NTTN but can only use half, it cannot lease the remaining capacity to other ISPs.

But if allowed sharing, this could have reduced operational costs of the small net providers. Besides, shared infrastructure could have minimised overhead cables, especially in densely populated areas.

However, the ban on resource sharing has forced individual ISPs to incur higher expenses, which are ultimately passed on to consumers, making internet services pricier.

Some providers allege that the restriction on active sharing is intended to favour the NTTN.

The ISPAB has been advocating for active sharing of infrastructure for years. In a letter to the BTRC, ISPAB said ISPs should be allowed to share active network resources in their access networks. This would not only reduce overhead cables but also enhance the aesthetic appeal of urban areas and improve service quality.

Current ISP licensing guidelines limit ISPs to installing optical fibre within a 3-kilometre radius in metropolitan areas and 6 kilometres in non-metropolitan areas.

The BTRC has also implemented a regulatory framework that sets fixed buying and selling prices for ISPs while mobile operators are exempt from such pricing mechanisms. This policy has created an uneven playing field in the internet service sector.

Industry insiders claim that ISPs have to pay an additional Tk 80 to Tk 120 per Mbps of internet compared to mobile operators due to these rules. This disparity puts ISPs, especially in rural areas, at a competitive disadvantage.

The fixed rates and higher transmission costs lead to higher internet prices in rural areas compared to cities.

"The additional costs incurred by ISPs in rural regions are often passed on to end users, further widening the digital divide," said Syed Almas Kabir, former president of the Bangladesh Association of Software and Information Services (BASIS).

He said that although transmission prices for wholesale internet should have decreased due to increased usage, these tariffs have not been readjusted in a long time.

According to BTRC documents, the commission set tariffs for transmission services in September 2021.

Aminul Hakim, president of the International Internet Gateway Association of Bangladesh, said the association recently proposed a 15 to 25 percent reduction in wholesale internet prices to the BTRC.

Another obstacle that has pushed up internet prices is the BTRC's complex and widespread revenue-sharing system.

Last year, the BTRC introduced a 1 percent revenue-sharing requirement for ISPs to contribute to the Social Obligation Fund (SOF).

ISPAB President Hoque said that under the "one country, one rate" policy, ISPs sell the internet at a fixed price with very limited profit margins. "If we have to contribute another 1 percent of our revenue to the fund, many ISPs may not survive."

Fahim Mashroor, former president of BASIS, said the BTRC has almost become an extension of the National Board of Revenue (NBR), which is not its intended role.

"They should act as regulators or facilitators, not as a money-making machine for the government," he said.

"As the government receives huge revenue from the BTRC every year, it is reluctant to make any changes," he added.

Meanwhile, Syed Almas Kabir advocated for eliminating intermediaries in the internet ecosystem, allowing ISPs and mobile operators to purchase internet directly from the wholesale market.

When contacted, Major General Md Emdad ul Bari, chairman of the BTRC, said the commission is reviewing different licensing regimes and working on various issues to reduce internet prices.

Nahid Islam, the adviser for posts and telecommunications, told The Daily Star that they are currently discussing with stakeholders to find ways to lower internet prices.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments