How is the economy doing?

Globally celebrated American musician's lyrics, "the answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind," might provide a poetic response—though not entirely. A portion of the answer about Bangladesh's economic trajectory can indeed be gleaned from tangible and verifiable realities.

The "blowing" element captures the uncertainty surrounding where the economy is heading. This uncertainty stems less from Bangladesh's economic fundamentals—like resource endowments, technology, geography, or culture—and more from profound unpredictability both locally and globally.

Not surprisingly, from the perspective of history, given the sudden political shift in August 2024, Bangladesh is yet to cohesively unite social forces in a way that drives sustained development. The silver lining is that the economy isn't falling apart. It has, in fact, managed to recover remarkably, coming from behind on several fronts amidst deep fragilities and hard bumps.

The point of departure

The post-August 5 political regime inherited an economy grappling with severe distress across multiple fronts. Concrete evidence of this distress was visible in data reflecting quarterly GDP growth, monthly inflation trends, escalating prices of staples like food and medicine, forex reserves held by Bangladesh Bank and domestic banks, rising non-performing loans, deteriorated assets in the banking system, accumulated arrears in the energy sector, mounting interest expenditures within the government budget, and the composition and scale of the government's domestic and public debt.

The White Paper dismantled the overly optimistic development narrative left by the previous regime. It presented a data-driven analysis of an economy stuck in a low middle-income trap, plagued by stagnating investment rates (quality concerns notwithstanding), a narrow manufacturing base reliant on an even narrower export sector, a persistently high share of informal production and exchange, a growing pool of youth excluded from employment, education, and training opportunities, a declining tax intensity falling below peer benchmarks, entrenched rent-seeking in markets, and systemic corruption in public service delivery.

Yes, Bangladesh did face significant spillovers from successive global crises. High inflation, tight financial conditions, a stronger US dollar, and weak activity in large economies amid heightened geopolitical tensions have characterized the post-pandemic global landscape. But the real question is why Bangladesh, unlike many of its peers in South and East Asia, fared so poorly in responding to these challenges. This is attributable largely to domestic policy failures.

Recovery and stabilisation

Over the past nine months, Bangladesh's economic path has been marked by a mix of progress and enduring hurdles. Gradual improvements in key indicators have emerged despite Dhaka—the centre of Bangladesh's economic gravity—being mired in regular demonstrations, often bringing disruptions to daily life and traffic, almost as if woven into the city's routine.

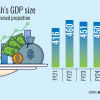

One of the most noteworthy shifts is the recovery in GDP growth. By the fourth quarter of 2024, GDP expanded to over 4%, a significant improvement from the dismal 2% recorded in the first quarter. Despite being below the historic corrected average of 4.2%, it marks a positive turn driven primarily by industry.

This recovery is mirrored in other indicators of economic activity, such as merchandise exports, which averaged $4 billion per month from July to April in the current fiscal year, compared to $3.4 billion per month last year. Similarly, remittances climbed from $1.75 billion per month to over $2.7 billion per month during the same period, probably reflecting, at least in part, slumping illicit financial outflows. Imports rose from $5.2 billion per month to $5.5 billion per month from July to March. The government was successful in providing uninterrupted electricity, notwithstanding the changed political economy in the sector and frequent gas shortages.

Inflation has decreased by 172 basis points since December, reflecting some easing of price pressures that had been fuelled by high food and energy costs, as well as rising import prices due to the depreciation of the taka and expansionary policies. Signs of relief became evident in the third quarter of FY25. Bangladesh Bank has maintained a firm monetary stance. The real policy rate turned positive in January 2025, marking the first occurrence of such a shift since February 2020.

Forex reserves, which experienced post-Asian Clearing Union lows, have seen a modest rise, with net international reserves consistently hovering in the $15–16 billion range. The narrowing of the current account deficit and persistence of the financial account surplus helped the overall balance of payments deficit to decline. Banking system net forex balances maintained positive daily positions between $200–700 million. Correspondent banking relationships, which faced setbacks in the aftermath of July 36, are gradually normalising. Government arrears have declined steadily. The differential between risky and risk-free interest rates is returning to relative normalcy.

Fragilities and bumps

These improvements coexist with significant underlying issues. Labour market weaknesses persisted through the second quarter of FY25. Both employment and real wages are down, indicating demand weaknesses affecting vulnerable populations disproportionately and widening social and economic disparities. The World Bank's April Bangladesh Development Update projects an additional 3 million people pushed into extreme poverty in 2025.

Weaknesses in labour demand are corroborated by subdued domestic and foreign investments. A historic low of $812 million per month in capital goods imports between July and February FY25 indicates bearish sentiment among investors. Capital goods import degrowth is also persistent in LC opening data. Private credit growth has hit recent lows. The frictional undercapacity in key industries such as textiles, garments, steel, and ceramics—exacerbated by energy shortages—constrains production and employment potential.

Financial distress remains pronounced, afflicting numerous state-owned banks and several private domestic banks. Both revenue collection and expenditure growth have regressed, reflecting systemic speed breakers. Bureaucratic inertia and unpredictably variable regulatory practices continue to hamper effective governance and economic management. The ability to identify problems, make informed decisions, and implement solutions in time is somehow unable to grow to scale in public administration. Corruption is thriving in a culture of impunity the nation is begging to be dented.

Global trade and geopolitical shocks are anticipated to influence FY26 significantly. The extent of these disruptions remains uncertain due to deep and wide policy ambiguity on the international stage. According to the World Bank, the combination of a global economic slowdown and rising inflation could lead to reductions in Bangladesh's exports and real GDP growth by 1.7 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively, compared to earlier forecasts. Despite these headwinds, GDP growth is projected to rise from an estimated 3.3% (World Bank) to 3.9% (IMF) in FY25, to 4.9% (World Bank) and 6.5% (IMF) in FY26.

Rising to the occasion

Bangladesh stands at a juncture where existing rules are being contested, while new ones are yet to emerge. Political change is inevitable, but its form and impact remain uncertain. The economy can never be decoupled from the larger political ecosystem. The shockwaves in this nest make effective macroeconomic management and structural reforms more critical as well as challenging, to unlock sustainable growth, equity, and resilience.

Good economics does not naturally lead to good politics. Policymakers should recognise how economic reforms affect political equations and anticipate resistance from entrenched interests. Long-term economic success depends on building institutions that constrain political actors from making decisions harmful to economic progress. Failure to rise to the post–August 5 occasion to build such institutions will make 2025 a year of missing yet another path-changing opportunity.

Dr Zahid Hussain is a former lead economist of the World Bank's Dhaka office

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments