How well founded are the devaluation worries?

In an interview published in this newspaper on January 3, the finance minister stated unequivocally “no currency devaluation”. Is such a sweeping stance compatible with the government’s own economic policy objectives?

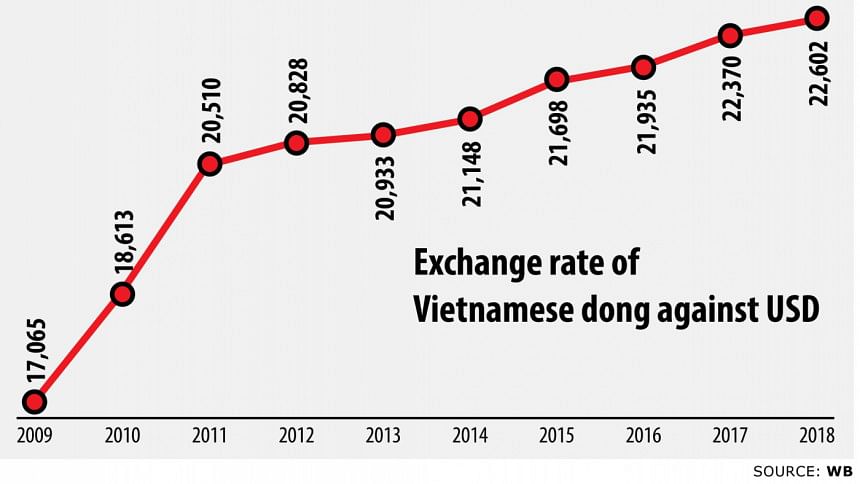

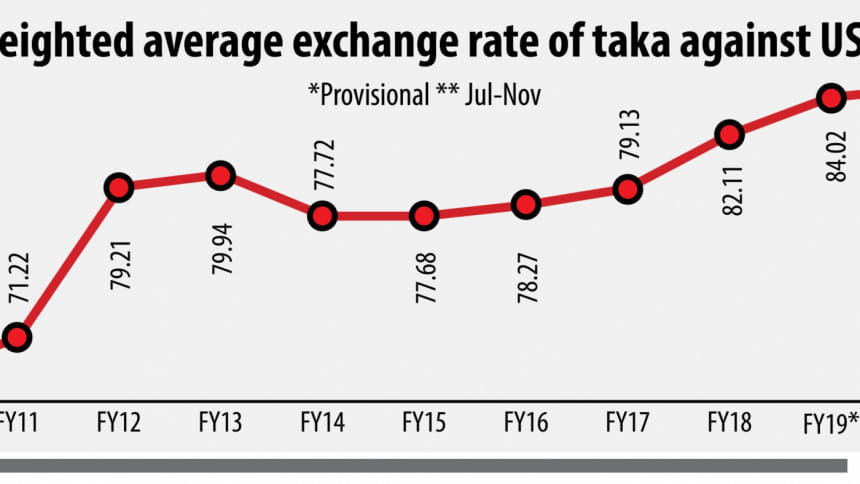

Exports have been declining recently. Exporters argue this happened partly because our main competitors such as Vietnam allowed its currency to devalue more than us. As a result, its exports became more price competitive relative to ours. Vietnam’s exports increased 9.6 percent in July-October while ours declined by 6.8 percent during the same period.

The finance minister is justifiably concerned about the effect of devaluation on the cost of imports. He does not want to devalue because the Bangladesh economy is highly import-dependent. The increased cost of imports will increase inflation. “We will die,” he said.

Let’s check the facts. Vietnam’s annual import is about $225 billion, constituting over 92 percent of its GDP. Bangladesh’s annual import is $66 billion, constituting about 23 percent of GDP. Clearly, Vietnam’s economy is more import-intensive than the Bangladesh economy.

Since November 2018, Vietnam has allowed 1.6 percent devaluation of its currency, while Bangladesh allowed 1 percent. Inflation in Vietnam rose from 2.98 percent in December 2018 to 3.52 percent in November 2019 whereas in Bangladesh it increased from 5.35 percent to 6.05 percent during the same period. Vietnam devalued more with less inflation while Bangladesh devalued less with more inflation.

Import prices are not the only determinant of inflation. Also, the impact of devaluation on the cost of imports can be mitigated through compensatory adjustment in import duties.

On other occasions, the finance minister expressed worry about the negative impact of devaluation on foreign direct investment (FDI). Let’s check the facts again.

Vietnam attracted $29.11 billion in the first 10 months of 2019 while Bangladesh attracted $2.5 billion during the same period. Vietnam devalued more with more FDI while Bangladesh devalued less with less FDI. It is generally accepted that a devaluation increases foreign direct investment flows.

The finance minister worries that devaluation would escalate the cost of development projects. There are numerous factors that increase project cost. In Bangladesh, delays are a major factor. The exchange rate is relevant when contracting services or other elements of the project are purchased from abroad. If exchange rates change beyond the level predicted by the project sponsor, the cost of the project can increase. An extra element—contingency—provides cover against cost over-runs due to exchange rate changes. The impact of devaluation is, therefore, never as large as appears at first sight.

Another worry is devaluation makes foreign currency denominated loan servicing more costly. This is true when we calculate foreign debt servicing in the taka. The case for keeping the exchange rate unchanged on this ground depends on the impact of the devaluation on revenues and the cost of servicing domestic debt. Devaluation can increase revenues if the value of imports in local currency increases and by boosting production of exports as well as import substitutes. Interventions to stem currency depreciation deplete banks’ taka liquidity. Interest rates rise, increasing the default risk and the cost of servicing domestic debt. Thus, on balance the fiscal impact of devaluation may be either a wash or even favourable despite increase in the local currency cost of foreign debt servicing. Because of these mixed effects, empirical studies internationally find no perceptible influence of devaluation on fiscal deficits.

In general, when markets are allowed free play, foreign exchange rates are determined by the supply and demand of foreign currency. However, foreign exchange markets are rarely allowed complete free play in any country. Central banks often intervene to smoothen volatility and provide uniform protection to domestic industries. Macroeconomic policy makers in Bangladesh deserve kudos for not doing anything to trigger disruptive volatility in the exchange rate. The practical question facing our policy makers is whether, through exchange market intervention, you want to take your chances on the side of under-valuing or over-valuing our currency.

Undervaluation of the exchange rate is, in fact, an industrial policy to promote growth in sectors producing internationally tradable goods and services. Undervaluation provides a subsidy to exports directly and automatically while protecting the domestic producers of import substitutes by increasing the cost of imports. It does not require a bureaucrat to select possible beneficiaries. Several Asian countries have used such strategic exchange rate policy to promote domestic manufacturing.

This non-selective industrial policy promoting tradable seems to be quite efficient, especially in countries with high levels of corruption and poor-quality institutions. Selective policies rarely work in developing countries where the quality of bureaucracy is far from perfect. The finance minister appears to have reawakened to the latter when he lamented “does anything happen according to timeframe in Bangladesh?”

Paradoxically, industry leaders in Bangladesh have revealed a preference for selective policies time and again. If correcting the overvaluation of the exchange rate through devaluation can produce the same industry specific result as a direct cash subsidy, should they not opt for the former than latter? Do not expect the industry to say yes, because it is in their self-interest to get both. However, when choosing between the two, they insist more on the latter because they do not have to compete with all others to benefit from the devaluation whereas the targeted subsidy is a lock-in for the insiders.

The finance minister is willing to provide Tk 5 cash subsidy per dollar of value added over imports to garments to compensate them for the overvaluation of the taka. What about non-garment exports? Won’t this policy deepen our over-dependence on garments? Since the subsidy will be based on value added over imports, will this not encourage garments to under-invoice their imports when claiming subsidies, thus making corruption more profitable than it already is?

Our policy stance on the exchange rate has so far favoured taking chances with the overvaluation of the taka. This policy is inconsistent with the strategy of diversified tradable production-based industrialisation.

The author is an economist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments