Inside the lives of RMG workers

In the shadowy predawn hours, the air in Ashulia, a small industrial town on the outskirts of Dhaka, is thick with anticipation.

The rhythmic hum of sewing machines will soon fill the air, heralding another day for the world's second-largest garment-exporting nation.

But before the machines roar to life, a different kind of movement begins – the quiet exodus of thousands of garment workers from their homes to the factories that dominate the landscape.

As the first rays of light break through the smog-heavy night, Rubiya Akter, a 30-year-old garment worker, emerges from a tin-roofed shack.

Her calloused feet hit the dusty path, each rhythmic step a testament to years behind a sewing machine.

Rubiya's day begins long before the sun dares to peek over the horizon, a brutal schedule dictated by the relentless demands of the fashion industry.

"I leave my children alone all day due to the immense pressure of work," she said.

Rubiya's long work hours and meagre wages exemplify the plight of lakhs in Bangladesh, where the demands of global fashion brands clash with the realities of the labour force.

Behind Rubiya, in the tiny tin shed she calls home, lie her most precious treasures: her daughter Omi, 6, and son Rakib, a Secondary School Certificate (SSC) candidate.

The single room that houses their dreams is a masterclass in resourcefulness. A single bed, where her children sleep soundly, hogs most of the space. Clothes hanging on the walls serve as a colourful tapestry of their life, each garment a story of careful budgeting and maternal pride.

In one corner stands an old refrigerator, a prized possession acquired through months of saving. But more often than not, its dim hum is all the comfort it offers. The shelves inside lay bare, a stark reminder of the family's financial standing.

Housing conditions are cramped and facilities are stretched thin.

"We have only two bathrooms for 10 families. We have to stand in line every morning," Rubiya said.

Education, seen as a path to a better future for future generations, comes with its own set of obstacles. "The kids walk to school, which takes an hour. All the schools are one hour away from our house."

Healthcare accessibility also proves challenging. The nearest affordable medical facility, Gonoshasthaya Kendra, is a gruelling journey away.

"It takes almost 2 hours on the road, but we go there for medical treatment as it is less expensive."

The arithmetic of survival

As Rubiya walks, calculations race through her mind.

Her monthly salary of Tk 12,800 – hard-earned through countless hours of stitching and sewing – seems to evaporate before her eyes.

The numbers dance in her head: Tk 3,500 for rent, Tk 500 for electricity, Tk 6,000 for food and basic necessities.

The remaining Tk 2,800 must somehow be stretched to cover her children's education – Omi's school fees and Rakib's crucial SSC exam preparations.

"Sometimes I can't even pay tuition fees," she admitted, the weight of stress evident in her voice. "I need to borrow money frequently. It's a cycle that never ends."

In Ashulia's kitchen market, four eggs cost Tk 65, broiler chicken Tk 200 per kilogramme (kg), beef Tk 750 per kg, onions Tk 120 per kg, and green chilis Tk 70 per kg.

"I generally cook small tilapia fish for my children as I can't afford beef," Rubiya explained. "There was a time when I tried to purchase eggs every day, but due to price hikes, those are now out of reach."

Speaking about the standard of living of RMG workers, Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmmed, executive director at the Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies (BILS), said real wages had not increased greatly because of persistent inflation.

According to the cost of living indexes of various government institutions, including the Bangladesh Bank, it is not possible to live on Tk 12,500, the minimum monthly RMG wage.

"Our government has not adopted any programmes for workers' welfare for a long time. There is no initiative to improve industrial areas with schools, hospitals, markets, housing, or transportation. The civic benefits and social security of workers should be ensured regionally. Again, at the factory level, workers do not have the opportunity to express themselves, so their needs are not known."

Stories of struggle

Rubiya's story is not unique. Similar tales of hardship echo throughout the narrow alleys and crowded worker houses in Ashulia, home to over 407 garment factories.

Shahida Khan, 37, works as an operator from 8 in the morning to 10 at night. A single mother, she supports her university-going daughter on a monthly salary of Tk 12,500.

Including overtime, she earns a maximum of Tk 16,000.

"My daughter lives in Dhaka," Shahida shared. "Her semester fee is Tk 3,000. Plus, there's her sublet rent. I can't save any money for her future. Meat is a dream for us."

Nearby, Polash Mahmud and Jasmin Akter struggle to balance work and family. Their 4-year-old son lives with relatives in their village home of Jamalpur, a heart-wrenching decision driven by necessity.

Polash mentioned: "I used to be the sole earner, but now my wife also works at the factory to help make ends meet."

Due to their struggles, they have had to sacrifice their role in raising their child.

"We've sent our son to the village as we don't have enough time or money to take care of him," Polash explained. "We have to send Tk 2,000 home each month. Mostly, I have to buy basic commodities on credit. There's no money left for medical and other necessary expenses."

Polash and his wife rent a small room for Tk 4,000. "The environment here is poor. When it rains, our house floods due to water logging, but we stay here to save on transport costs."

Hosna Akter is a 24-year-old mother of one child who has been working in a garment factory of Mirpur for more than five years. She was getting Tk 13,550 as a senior operator.

After working for five years, Hosna's husband Manna, an operator, earns Tk 13,800.

The couple's monthly expenditure includes Tk 6,000 for rent, Tk 400 for electricity, Tk 500 for internet, and Tk 8,000 for groceries – more than 54 percent of their joint earnings. Then there is the money that they have to spend on their child.

Hosna and Manna recently resigned out of frustration, deciding they would be better off if they relocated to their village.

Another worker from Mirpur, Shanta, has processed her way to Jordan to work as a labourer as she found it impossible to meet her expenses with the low pay in the garment sector.

A system under pressure

Data from the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) shows that there are 3.3 million workers in garment factories, with 52.28 percent being women.

Although the industry provides crucial employment, it also operates on razor-thin margins. Factory owners, under pressure from global brands to keep costs low, often struggle to improve working conditions or raise wages significantly.

Dr Rubana Huq, a former president of the BGMEA, said: "Tk 12,500 is not the ideal salary but because of not getting the prices from buyers and the declining value and volumes of the clothes, there is little scope to give anything more. Thus, we need to think about non-wage benefits such as transport, housing, and food subsidies. These are the areas that the government must consider. Manufacturers need to come forward too."

She added that workers must be given education and healthcare benefits.

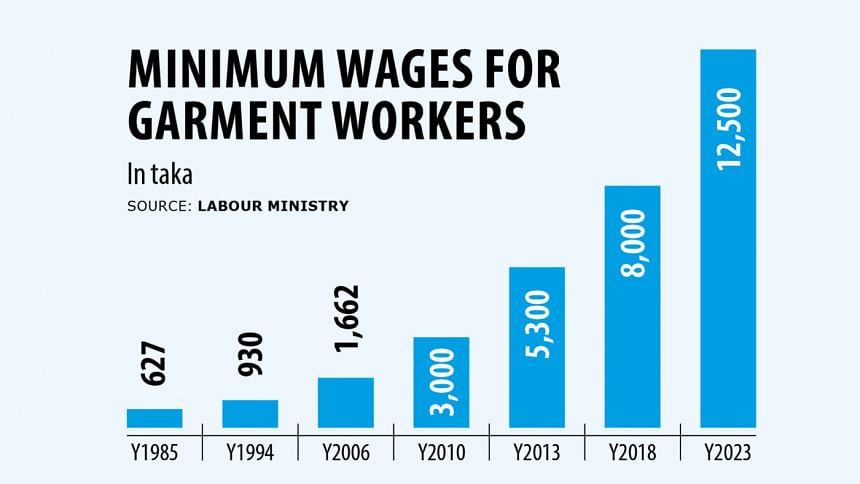

Last year, workers protested for an increase in their monthly minimum wage to Tk 25,000. After negotiations, the government settled on Tk 12,500 for entry-level workers in the RMG sector – a 56 percent increase from the previous Tk 8,000, but still far below what workers say they need to live with dignity.

Of the amount, Tk 6,700 has been fixed as basic salary, Tk 3,350 as the house rent, Tk 750 as medical allowance, Tk 450 as conveyance, and Tk 1,250 as food allowance.

Bangladesh's garment exports reached $32.86 billion from July to February in fiscal year (FY) 2023-24, up 4.77 percent year-over-year, according to the Export Promotion Bureau (EPB).

The Export Promotion Bureau (EPB) noted that garment exports during the first two months of this year amounted to $9.47 billion, registering a 13.15 percent year-on-year growth.

Khondaker Golam Moazzem, a research director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), opined: "The structure of the minimum wage is faulty. Allocations for basic housing and medical expenses are far less than required. Besides, some other expenses are important – child education, communication expenses, entertainment, and internet bills. These are not in the salary structure."

He added that workers did not compete on an even footing when it came to negotiating for better wages and working conditions.

"The wage negotiation should be tripartite, including the government, workers and owners. But in reality, the decision comes in a bipartite fashion – from the government and owners only," Moazzem said.

"Workers fear that they may lose their jobs during these negotiations. Meanwhile, owners argue that higher wages would increase costs and reduce competitiveness, though there's little evidence supporting this.

"According to the Bangladesh Labour Act, there are 12 indicators for wage negotiation, but only two or three are used. Ultimately, wage negotiations in our country are not data-driven and owners tend to avoid them."

The human cost of fast fashion

As the sun sets on another gruelling day, Rubiya makes her way home. Her fingers are sore, her back aches, but her resolve remains unbroken. Tomorrow, she'll do it all again.

The stories of Rubiya, Shahida, Polash, Jasmin, Hosna, Manna, Shanta and countless others serve as a powerful reminder of the human cost of the price tags we see in stores.

Some expressed plans to leave the industry if the situation of workers does not improve, agreeing that it's better to settle in their village homes.

As night falls, the factories finally fall silent. But in countless tiny homes, the struggle continues – a testament to the resilience of those who stitch our clothes and, in doing so, weave the very fabric of their dreams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments