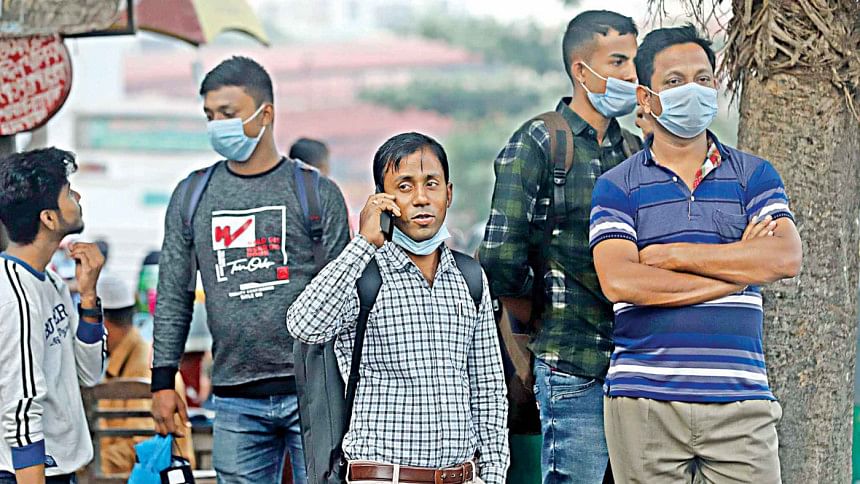

Recovering employment after Covid-19 outbreak and beyond

Despite showing signs of recovery, there is no denying the fact that the Covid-19 outbreak has resulted in a strong dent on the country's development efforts.

According to the projection of the IMF, Bangladesh is expected to be one of the top performers in terms of economic growth in 2020. Such news though deserves appreciation, and we must keep in mind that meaningful recovery should be associated with recovering livelihoods of millions who have lost their employment or suffered a loss in income.

Besides, with the second wave of infection already affecting our trading partners, the scenario of employment generation and recovery through large-scale export-oriented industrial activities is not that optimistic as well.

In addition, the inflow of foreign remittances though acting as a key driver of economic recovery, many of the potential migrants along with the returnees are finding it difficult to explore the foreign labour markets and will eventually join the pool of local labour force.

Against this backdrop, the task of recovering employment and income is indeed a daunting one.

As for the impact of the Covid-19 on the labour market, though a significant proportion of coronavirus-induced temporarily unemployed have regained employment and the business owners been able to revive their business activities in recent months, some are still struggling to find a new job or to re-open their businesses.

Besides, many of the self-employed are yet to regain profitable business activities as before. In order to confront such challenges of the labour market, change of job, mainly to a relatively inferior one, has been a coping strategy for many.

Migrating back to the rural areas and thereby curtailing the expenses of urban dwelling has been a strategy as well, at least for the short term for some of the households.

The coping strategies in the face of employment and income shock often have included depletion of assets and savings to meet current expenses during the time of income shortfall.

Such strategies can, however, have long-term consequences on the ability of capital accumulation for establishing new businesses or for expanding the existing ones.

While designing relevant strategies and policies for confronting the coronavirus-induced challenges, it must be kept in mind that even prior to this pandemic, several constraints existed in the labour market of Bangladesh.

The question, therefore, remains whether our target is to recover the labour market to its pre-existing level or to deal with the inherent challenges through a broader and longer-term vision?

In this context, one such challenge of the labour market is unemployment and more importantly, youth unemployment.

According to 2016/17 Quarterly Labour Force Survey, youth (18 to 29 years) unemployment rate was as high as 10.6 per cent as opposed to the national average of around 4.2 per cent, with as high as 29.8 per cent of youths being not in employment, education or training (NEET).

There is no denying that such unemployment problem has both supply and demand-side obstacles. For example, with as high as 8.79 per cent of youths having no formal education and only 5.90 per cent having tertiary education, the youth labour force is not endowed with required skills consistent with the growing demand.

Besides, it is not only the youths per se, majority of the workforce still consists of those engaged in mid-skill occupations (47.5 per cent), with only around 8.9 per cent being in high skill occupations.

The slow growth of large-scale industrialisation due to the Covid-19, coupled with changes in the production process due to increased automation and fourth industrial revolution and the declining importance of routine and manual tasks, the challenges of employment are more significant than ever before.

The other side of this shortage of skilled labour force is the persistent mismatch of skills between the supply and demand side of the labour market with high (11.2 per cent) unemployment rate of those even with tertiary education.

It is, however, not only employability per se, in the absence of trade unionism and minimum wage legislation in many of the sectors, meeting the requirements of the decent job as required by the ILO is indeed a key challenge of the labour market as well.

In order to recover the livelihood of the people in a true sense, confronting the Covid-19-induced challenges will therefore not be enough -- the policy focus must be towards resolving the bigger constraints.

While short-term strategies, on the one hand, should be directed towards regaining business confidence and stimulating private investment, priorities should be centred around an effective implementation of existing incentive packages for the SMEs in particular.

In this regard, alternative financing arrangements involving the microfinance institutions (MFIs) and further relaxation of the terms and condition of loans for the relatively smaller firms should be considered on an urgent basis.

Preparation of nationwide database along with quick and low-cost registration services would help the informal firms and returnee migrants avail the incentives.

With a declining employment elasticity of growth (employment elasticity fell from 0.55 between 2005/06 to 2009/10 to 0.25 between 2009/10 to 2017/18), the long-term focus should, however, be on the job-creating capacity of GDP growth rather than on the growth numbers per se.

Also, the declining importance of routine intensive tasks and challenges of both the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) and increased automation requires productivity enhancement of the labour force.

On the one hand, emphasis should be on modernising skill training programmes involving cognitive and interpersonal skills. On the other hand, mainstream education programmes need to be aligned with the changed demand of both local as well as global markets.

Furthermore, we must take into account the fact that the Covid-19 has posed additional challenges of long-term skill formation due to dropout of students at different stages of education along with a digital divide among students.

Urgent policy focus is required to this end to bridge the gap and support those at the lower end of the distribution.

The writer is an economics professor at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments