The economics of social distancing

Social distancing has proven to be an effective weapon for dampening the spread of coronavirus.

According to some studies, at least 70 per cent of the population need to stick to social distancing to make a serious difference to flattening the virus spread curve.

Yet, widespread non-compliance with social distancing norms looks like a norm in many places. Why?

Social distancing is a public good. The benefits from actions taken for social distancing spills over beyond the person taking the action (non-rivalrous).

These spillovers cannot be withheld from people who do not take part in its provision (non-excludability).

Not needing to take part in social distancing actions to benefit from it inevitably induces many to be lax in their own social distancing actions (the free-rider problem).

The virus spread reduction result produced by my actions on social distancing depends on the social distancing actions taken by others on whom I have no control. And vice-versa. Masks worn by others will not necessarily protect them if I don't do the same.

To get a deeper understanding of the implications of these externalities, it helps to simplify the problem.

Imagine a world of just two individuals -- A and B -- who are suddenly hit by a virus that immediately reduces their welfare.

Both realise that social distancing is an effective behaviour change needed to contain the virus contagion.

They are also aware of the interdependence of the costs and benefits of their social distancing actions.

Each has to decide whether to do or not do social distancing under these circumstances.

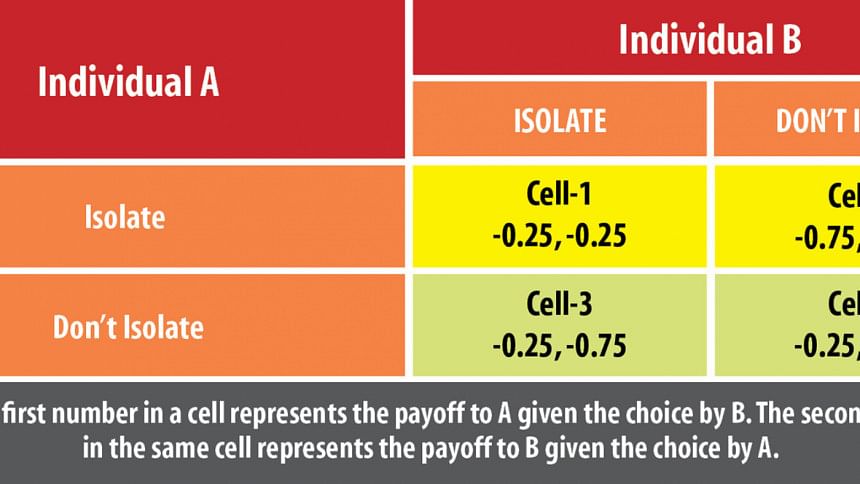

To simplify further, suppose it is a binary choice between isolating and not isolating. The payoffs from these actions, measured in units of individual welfare (Utils), are described in the table.

When the virus hits, the two individuals suffer a welfare loss of 0.25 due to the risk of contracting the virus (Cell-4).

Isolation leads to an income loss of -0.5 to each individual and reduces the risk of contracting the virus by 0.25.

The latter happens only if they both isolate at the same time.

If A isolates but B does not, the loss due to the virus risk remains at 0.25 for both. Consequently, A's total loss is 0.75. B avoids the income loss and therefore his total loss remains at 0.25 (Cell 2).

If B isolates and A does not, the payoffs are the opposite (Cell 3) because both A and B are assumed to face identical distribution of risk and income losses.

If both isolate at the same time, they lose income (0.5) and reduce the virus risk (.25), leaving each of them with a net welfare loss of 0.25 (Cell-1).

What is the optimal choice for A and B in the aftermath of the virus, given the uncertainty about what the other person will do?

Consider the problem from A's point of view. If she stays put, her loss is 0.25. If she isolates and B does not, the loss rises to 0.75. If B also isolates the loss is 0.25, same as in the initial situation.

Assume both individuals are loss averse. Losses loom larger than gains. As argued by Kahneman & Tversky (1979), the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

Both A and B are more willing to take risks to avoid a loss than to make a gain. This leads to a bias in favour of the status quo.

Since there is no gain but only a possibility of loss if B does not isolate, no matter what B does, the best choice for A is to not isolate. The problem is symmetric for B. So, the best choice for him is also to not isolate.

The numerical illustration assumes both the individual and the sum of their welfare in the initial situation are the same as when both are isolating. Further, the sum of welfare loss when one is isolating while the other is not is greater than when both are isolating (Cell-1) or when both are not isolating (Cell-4).

It is because of the income losses which the one who isolates incurs, but this has no impact on virus risk reduction because the other person is not isolating.

This is an important assumption whose empirical validity is now under experimentation all over the world.

However, allowing some virus risk reduction due to unilateral social distancing action by an individual will not change the key conclusion that social distancing actions are underprovided when left to individuals' own volition.

Synergy -- the combined virus reduction effect when most are cooperating is greater than the sum of their separate effects -- does not enter the individual payoff calculations.

Such externalities accrue relatively trivially to the individuals taking the action and largely to third parties who face less transmission risk.

However, since the benefit to the third parties is not appropriable to the ones engaging in social distancing, it does not appear in individual decision-making calculus.

Social distancing is underprovided because the externalities are not internalised.

The payoff matrix above will change dramatically if the 0.25 gain to the other person enters into each individual's calculation. This will happen under unconditional altruism.

The virus risk reduction gain to each individual will double in the cooperative equilibrium (Cell-1) because each care equally about the other person's gain.

Anything that promotes internalisation of externalities can produce a shift from the initial trap to greater collective welfare.

Costs of social distancing actions and altruism matter. When the costs are low, people do comply.

Wearing mask, gloves and keeping a 6-feet distance when out and about, including when meeting other people, are such low-cost actions that are gradually gaining universal acceptance (except for some such as the US President Donald Trump). They are also getting entrenched in social expectations.

If everybody is complying with behavioural social distancing, the defector is likely to suffer some stigma.

There is anecdotal evidence of violent protests by people in stores and aeroplanes against those not wearing masks.

Altruism explains why many in all parts of the world chose not to physically visit mothers on Mothers' Day.

Public communication promoting enlightened self-interested behaviour -- acting to further the interests of others to ultimately serve one's own self-interest -- works well in these cases.

Voluntary home confinement day after day is a whole different ball game. At the individual level, this is a trade-off between the risk of contracting the virus versus losing livelihood for a vast majority in rich and poor countries alike.

Given the perceived costs and benefits and the uncertainty about what others will do, the certainty of losing livelihood weighed against the uncertain benefit of virus risk reduction induces each individual to not isolate.

Interventions compensating the income loss conditional on social distancing will make it in the self-interest of both individuals to isolate themselves.

In the presence of adequate (in this case equivalent to slightly higher than 0.5) social protection, by not isolating, both lose more than what they are losing any way irrespective of what the other person is doing.

The breaches in compliance are too varied to be fully explained by the absence of altruism or public action.

The uncertainty around the virus about how many people are infected, what role asymptotic people have in transmission, what is the true fatality rate and so on creates a sense of fatalism or invisibility about the spread of the virus.

People tend to focus on the here and now when faced with an uncertain and poorly understood calamity.

Infection risk tolerance thresholds vary from person to person.

Individuals start social distancing at different levels of disease prevalence.

The more risk-tolerant individuals, and not just the younger generations, free-ride on the efforts of the less risk-tolerant.

Belief in herd immunity increases risk tolerance, with Brazil and Sweden being the most obvious cases.

The emergence of new social norms penalising non-compliance can induce voluntary compliance by aligning individual and collective interests.

Indeed, such norms appear to be emerging organically or through public action.

In South Korea, it's called "everyday life quarantine". People ordered into self-quarantine download an app that alerts officials if a patient ventures out of isolation. Fines for violations can reach $2,500.

South Koreans, remembering the mistakes made in the handling of MERS and SARS, have accepted invasive personal information exposure that is inconceivable in Europe or North America.

Structural conditions play an equally important role in enabling compliance with different social distancing rules.

Some communities cannot wash hands because of limited access to water.

Vulnerable groups find staying a metre away from others within or outside their households nearly impossible.

Richer people have an easier time engaging in self-isolation because they can work from home in nicer and roomier space.

They have internet access that mitigates the cost of reduced face-to-face interaction. The poor have no such luxuries.

They cannot afford to internalise the social cost of risk-taking.

It is not realistic to expect individuals to be forward-looking when they have to spend sleepless nights worrying about surviving the present.

Research shows the problem of non-compliance is exacerbated when people live in more unequal communities.

Psychology is powerfully influenced by the social environment we inhabit.

This environment structures daily life and relationships in workplaces and neighbourhoods.

The less socially entrenched people are, the less collective action is in their self-interest.

Social pressure, norms and moral suasions do not resonate when you feel you are a dispensable thread in the social fabric.

Solidarity is hard to forge in social environments that either does not have a proper norm, such as under what conditions markets can reopen, or the norms are fluid, as the chaos in the garments industry demonstrated.

Maintaining communitywide social distancing for long gets tougher when solidarity and trust are low.

Public health is determined by the least common denominator.

If the poorest and most marginalised within a society are not protected, then no one is.

The author is an economist

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments