Towards a more conducive tax system: reform strategies and priorities

The Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare around the globe the need to strengthen domestic revenue mobilisation systems of countries, particularly in developing nations. Given the imperative of harnessing resources to combat the extremely deleterious effects of the pandemic on national economies, the revenue system in a country like Bangladesh, whose swift progress towards attaining developed country status has received an unexpected shock, does come in for some examination.

Major economic shocks are affecting global markets, culminating in lower or negative growth, higher unemployment, rise in poverty, and acute fiscal pressure for countries around the world. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects the global economy will contract by 4.4 per cent in 2020 while emerging and developing Asia will grow at an estimated negative 1.7 per cent.

Bangladesh too, having displayed a robust average growth of more than 7 per cent over the last decade, will witness a lower growth. There is, of course, a rebound since June with positive trends in exports, remittances, and large parts of the domestic economy but several challenges continue to persist, including uncertainties in middle-east job markets, displacement of small enterprises, and loss of livelihoods or drop in income for millions.

While the current scenario is encouraging, the loss of the past several months will not be easy to recoup. For the export and overseas workers sectors, the state of the various customer and host countries will be major determinants in their performance going forward.

In the immediate aftermath of the Covid-19, the government of Bangladesh was quick and bold in announcing a massive $11 billion economic stimulus programme, equivalent to more than 3 per cent of the country's GDP; as well as direct fund transfers and food aid to the neediest.

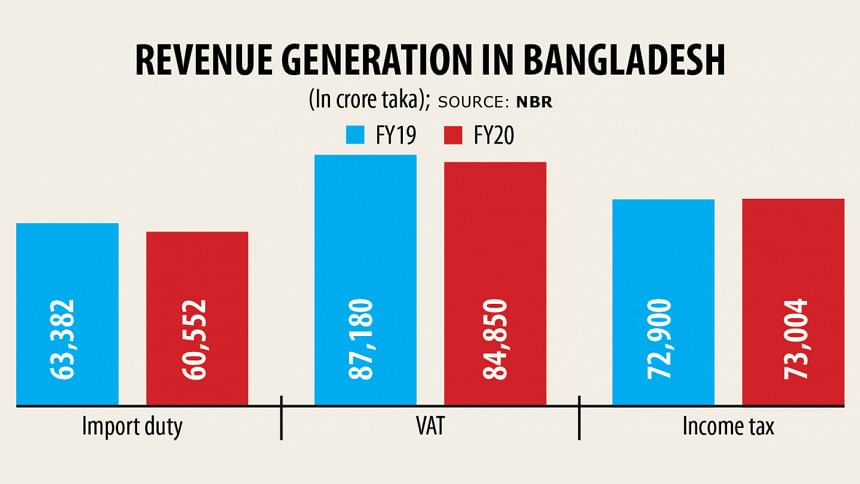

More than three-fourths of the total stimulus comes from bank credits, but the fiscal cost is significant – around 1 per cent of GDP. It is unarguable that although through past prudent fiscal management, the government has created significant headroom to manoeuvre even in these troubled waters, revenue generation will be strained.

Managing the health and economic crisis and necessary prudent measures to secure medium-term recovery require massive fiscal resources. Allocation of higher resources in the health sector, absorbing interest losses or subsidies in the banking sector, delivering direct assistance to the poor, forbearance in tax and other regulatory compliance, tailored policy and financing support will place a significant fiscal burden of the state.

Bangladesh's unprepossessing tax-GDP ratio, which hovers around the 10 per cent and below the mark, is not a healthy sign for the volume of revenue needed to be generated to keep the economic scenario as stable as in the last several years. The essential dialogue needs to begin now on how effectively to work towards increasing this ratio while lowering the monetary and regulatory burden of compliance on good taxpayers.

Securing these resources in a fiscally sustainable way, and how to manage them wisely are key policy questions for the government to address. Notably, the need to strengthen the state's capacity to collect tax revenue to ensure a sustainable debt-GDP position while funding essential public services such as health and social protection will require careful but immediate effective consideration followed by prompt action.

This may seem like an inauspicious time to contemplate significant reforms; however, in addition to potentially focusing the minds of policy-makers, large shocks can also provide opportunities to positively address political and bureaucratic resistance to significant change, thus opening new reform opportunities.

In addition to responding to the crises to mitigate its impact on the people of Bangladesh, this may be an opportunity to re-engineer processes to remove the discretionary application of laws and rules, as well as making them much more technology-drive, which will create a large measure of transparency and accountability.

One critical rationale for Bangladesh policy-makers at this moment that warrants a quick and effective tax reform programme is to make the country's business environment more conducive and supportive of the country's 'Developed Country' vision. The regulatory and institutional environment has many weaknesses which are reflected in global indicators and indices. Significantly, both domestic and foreign investors rank the taxation system and administration as one of the major roadblocks towards increasing private investment in Bangladesh.

Paying tax in Bangladesh is plagued with numerous policy and administrative complexities. The Doing Business 2020 reports that, on average, firms in Bangladesh make 33 tax payments a year, spend 435 hours a year filing, preparing and paying taxes, and pay total taxes amounting to 33.4 per cent of profits.

Despite a number of incremental reforms in recent years, the feedback from firms and the Tax Perception and Compliance Cost surveys indicate that there would have been more investment and growth, and more firms would have become formal enterprises if the tax regime were simplified. SMEs, particularly small enterprises, fear to formalise because of perceived difficulties related to the tax system.

Tax reforms are complex undertakings due to both political economy and technical considerations. Key issues have been much talked about for a long time here in Bangladesh with the business community, influential in their own right, often pleading for such reform.

The principal points of contention have been a lack of transparency, the exercise of discretion, unfair application of laws to meet revenue targets, sudden changes to tax rates and conditions for imposition, the irrational imposition of advance income tax and tax deductible at source, lack of any effective mechanism for adjustment or refund of excess tax paid, failure to expand the tax net significantly, among others.

Yet, very little has taken place so far, an indication that tax reforms, however impactful they may be, will be no easy task. It will be critical to understand the incentives of the important stakeholders relevant to the system, prioritise the reforms, and set the appropriate reform strategies.

Bangladesh can accelerate successful tax reforms by adopting best practices from the world and contextualising them to the country's ground realities. Widening and deepening of the existing tax base across all the three taxes will be critical in this regard. In this context, developing a technology-led tax administration and taxpayer services system is critical, both to align with the vision of Digital Bangladesh but also to address many inefficiencies, including minimising contact between tax official and taxpayers, discretionary behaviour, and improving transparency.

Setting up an efficient, integrated national tax accounting network that will correctly account for, reconcile and record tax payment information at a transactional level for all the three taxes and make visible this information in real-time basis to taxpayers and to all stakeholders, including the government, the National Board of Revenue (NBR), tax officers, Bangladesh Bank and taxpayers, is essential.

Better and easier tax compliance is a function of both enforcement and incentivising taxpayers. Enriched and enhanced taxpayer experience through measures of simple and quick taxpayer services available at the doorsteps of citizens and business, reducing compliance cost for the taxpayer by eliminating unnecessary paper works and contacts between tax administration and taxpayers, will help develop trust and relationship between tax authorities and the honest and diligent taxpayer. Research into taxpayer behaviour and motivation has proven to be an effective tool in providing inputs to tailor taxpayer experiences to specific types of taxpayers, resulting in better revenue generation.

The objectives of an effective tax administration system would be to reduce and minimise the costs of administration and compliance on both sides, ensure procedural fairness, avoid discretion and discrimination, ensure transparency and engender confidence in the system as far as the taxpayer or citizen is concerned.

With a fast-growing economy and capacity constraints on the part of revenue administration, embracing a risk-based approach in enforcing tax policies and compliance holds the key to efficient administration and taxpayer services.

Authorities must consider shifting tax compliance management from the traditional subjective audit selection approach to a technology-assisted intelligent selection approach based on efficient data mining and revenue risk management tools. Incorporating a culture of prioritisation in revenue administration will help keep tax officials from non-priority routine work which is often high-volume and low-knowledge, and focus more on priority compliance and tax collection work.

If a paradigm shift is required in the tax policy landscape of Bangladesh, what are the questions to ask? What kind of taxation should be prioritised and in what time-frame: direct taxes, trade revenues or indirect taxes? What is an effective use of withholding and advance taxes, which are currently not just inefficient, but unjust in practice? Should the system be organised around the different kinds of taxes or different kinds of taxpayers?

Effective segmentation of taxpayers has proven to be a good practice in many countries, but the Large Taxpayers Unit is perhaps not playing the desired role, rather has become burdensome on the taxpayers included in it. An ongoing public-private dialogue is essential between the business community and the NBR, but that does not take place. A mind-shift in treating the taxpayer as a client as opposed to a target and the taxation officers as facilitators as well as revenue collectors is also necessary.

In terms of establishing accountability, it may be the appropriate time to consider establishing the office of Tax Ombudsman, as well as including private sector members in non-executive positions in the revenue governance body.

The latter would, of course, need a significant change in the formation and working practices of the NBR. Examples of private-sector representation in the revenue governance body abound, including in Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Malaysia and Singapore. Sadly, over a fairly lengthy period of time, the NBR has not been able to make the alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanism for the resolution of tax disputes effective.

A firm political commitment is necessary for making perhaps the boldest yet the most critical tax reform measure necessary- separation of tax policy and administration. Setting policies and collecting taxes through the same institution not only creates a conflict of interest, but it also makes it impossible to have objective revenue targeting and necessary adjustments reflecting evolving economic conditions, and enforcing tax compliance.

The objectives of the tax system should not be just to collect and meet revenue targets. It should aim to increase the positive effect of the tax system on economic efficiency and growth. It should consider the impact of current taxation on future economic activity, and it should consider the impact of current taxation on future tax revenue generation. All of this also needs to be informed by the implications of international trade policies, as well as the taxation and trade policies specifically of our competitor countries. Needless to say, all this requires the capacity for data collection, analysis and research, which is not present in any significant measure in the current structure.

One of the key steps would be to increase the analytical capacity in order to provide solid data analytics to lay the ground to inform and prioritise both policy imperatives and decisions, as well as the necessary institutional and process-oriented reforms. Efficient revenue forecasting and the use of third-party information effectively would enhance the capacity to target sources of revenue fruitfully.

Change, as always, will not be easy since there is at least as much vested resistance as there is support. However, realising this vision, and the overall reform of the revenue regime, will require the strongest of political commitment with resolute follow through. At the end of the day, a good tax system is simple, equitable, transparent, accountable and responsive to the development goals of the country.

The authors are respectively the chairman of the Policy Exchange of Bangladesh and the president of the Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments