Expectations From 2021: Vaccination, education and sustained economic recovery

The new year always carries the legacy of the year gone by. Expectations for the new year are naturally conditioned by these legacies. This is true every year. But 2021 is starting from an exceptional footing. Preceded by a prolonged 10 months of unprecedented trauma and fear all the world over, 2021 inherits the legacies of a year that will go down in history as the most cursed in last hundred years.

Looking back

The pandemic caused the wheels of the global economy to brake and restart off and on as the virus found a way of striking back even in countries that excelled in flattening its' spread. Bangladesh like others had no immunity from the health and economic consequences of the virus. Thousands died and tens of thousands got infected. As in most countries, official statistics underrepresent the full extent of infections and fatalities.

The economy slowed like never in recent memory. Progress on poverty reduction and human development was partially reversed as the incomes from employment in services crashed suddenly, industrial activity suffered serious setback, trade faced major disruptions and schools remained closed since March till we still do not know when. A vast majority of the population receded down the income ladder while few lucky ones with higher order skills, digital access and elite connectivity prospered.

The never ending 2020 ended with a shining note of optimism as vaccines begun to emerge successfully from clinical trials. Yet the virus found a way of saying forget me not by mutating into a 75 per cent more transmissible new strain in several parts of the world including Bangladesh.

What then can we reasonably expect from 2021? While the wish list is long, expectations must respect the laws of the probable.

Fortification against the virus

Among these, fortifying the population with vaccination against the virus is central. Herd immunity through vaccination of a critical mass is the only permanent solution followed by cures or therapeutics. Until these are attained, public health measures such as testing, treating, and isolating couple with behavioural changes such as masking, social distancing, hand washing and so on are the only ways of containing the community spread of the virus. As we are learning from most countries, the latter are challenged by virus fatigue. It will therefore make sense to shoot for vaccination of a critical mass of Bangladeshi population by the end of 2021.

About 20 per cent population may be vaccinated by next June, according to some reports. High level government officials assure that the 120,000 centres under the Expanded Program on Immunization across the country can vaccinate 5 million people per month. This will not get us 20 per cent vaccination in six months even if we start from January 1. The government is reportedly planning to vaccinate slightly over 138 million people to achieve herd immunity. With 5 million vaccinated per month it will take 27.6 months to get there. This will complicate achieving herd immunity if the vaccines provide protection for only a year or so.

The existing immunisation workers are reportedly adept in post-vaccine risk management, cold chain monitoring and record keeping, including vaccine card preparation. But the existing numbers may be inadequate, thus requiring partnership with non-state actors to bridge the gap with adequate and speedy training for all. Procurement and distribution of the vaccine throughout the country will be a challenge unmatched in its magnitude by anything else in recent memory. Getting nearly 280 million dozes of the vaccine when rich nations have already pre-ordered dozes far exceeding expected supply will require more than just the ability to pay. Most countries facing severe Covid-19 epidemics are mature advanced economies with vast resources, strong institutions, and powerful administrative systems. This favours their capacity to acquire and distribute the vaccines as felt needed by their authorities.

Getting children back on learning track

Reopening schools to stem the acceleration in learning poverty is the second key expectation. This cannot wait for achieving herd immunity. The whole enterprise of online learning is plainly and irrevocably inadequate when a vast majority of school age population cannot access it. Evidence is already emerging that online learning is leading to an education gap that is almost certainly growing wider by the day. Children in poor households suffer disproportionately from school closures are missing out on school meals and find it harder to access digital learning in oftentimes overcrowded and poorly connected environments. Children are not learning. Worse, they are unlearning what they had learned before the pandemic. The lucky ones have digital access and parents who can take time off from work to help with lessons and maybe even conduct supplementary lessons of their own. Most families do not have such capabilities.

If the community transmission risk of returning to school does not appear to be high for either students or teachers, as the data seems to suggest, why are schools still closed in large parts of the country? There is growing international evidence that reopening is not only safe but, in fact, one of the few safe things a nation can do in a pandemic. Of course, we want to be safe than sorry. This means schools must be armed with an environment allowing access to testing, and adherence to masking, social distancing, and sanitisation practices. This is challenging but doable if the parents, public health specialists, teachers, regulatory authorities, and schools' management act in concert.

Surely, a solution can be worked out that would stop bleeding in learning. Our expectation from 2021 is to get back on track to achieving the reduction in learning poverty goals. According to the World Bank, 5 months of school closures due to Covid-19 can result in an immediate loss of 0.6 years of schooling adjusted for quality. Bangladesh was already struggling with a learning crisis prior to the outbreak of the pandemic.

Sustaining and accelerating economic recovery

Sustaining and speeding up economic recovery is the third major expectation. Covid-19 shuttered factories, curtailed domestic demand, postponed investments, and collapsed global trade. Unemployment, loss of income and inflation in healthcare prices pushed existing poor deeper into poverty and the vulnerable into poverty, including many middle-income households. This was particularly the case for household depending on the large informal sector without access to health care and social protection.

Putting poverty reduction back on track will require containing food inflation while restoring income and employment back to pre-pandemic levels. The latter were weak to begin with. All the key macroeconomic activity indicators such as exports, imports, private credit, VAT collections, industrial production, electricity generation and mobility, available monthly through November, suggest significant recovery relative to April-May, but either lower or close to the pre-pandemic levels in most cases. The largest services sector is stuck what may turn into a secular stagnation because of aggregate demand externalities. A simultaneous shock to income of a vast majority of households and relatively high contraction risk in human contact-based services have depressed demand for services in general, not to speak of demand for many fast-moving consumer goods.

A strong rebound in the global economy, propelled by the unleashing of pent-up demand as vaccination spreads in developed and emerging economies, will present renewed and expanded opportunities for exports of both merchandise and labour.

While successful immunisation will not act as an instant economic remedy, economies and businesses globally are currently expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021. Unlocking of strong pent-up demand in key economic sectors such as tourism, aviation, restaurants, entertainment, and medium and small businesses could subsequently generate economic expansion not seen in recent decades.

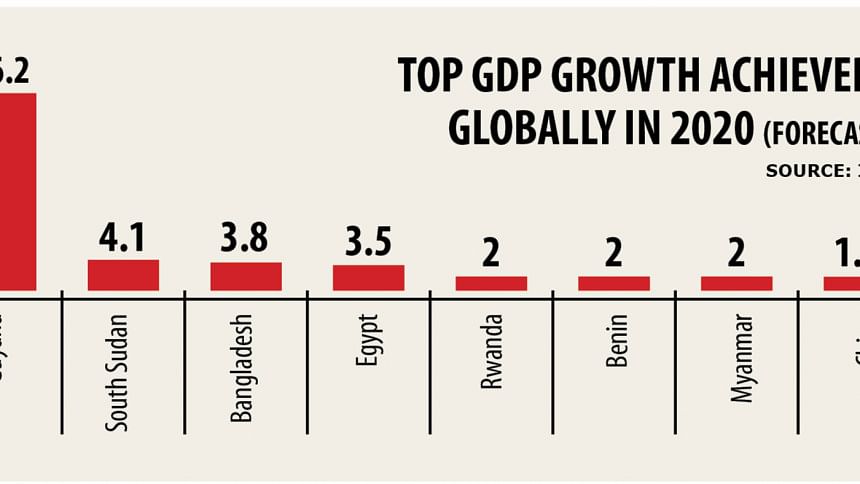

The IMF is projecting the global economy will grow by plus 4.3 per cent in 2021 and by plus 3.7 per cent in 2022. We expect to see Bangladesh get better organised in 2021 to reconnect with the process of a rejuvenated global recovery.

Effective public health measures such as ramping up testing and treating; behavioural change such as masking, social distancing and minimising congregated indoor gatherings; and improved design and implementation of policy support can be expected to revive feeble domestic demand and make the operation of supply chains safe.

But these will not be enough to trigger up the animal spirits that drive private investments. Structural reforms, policy predictability and macroeconomic stability will be key to earn the financial votes of confidence from the local as well as foreign entrepreneurs and investors.

The writer is the former lead economist at the World Bank's Dhaka office.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments