What will happen when overseas employment and remittance dip?

Among all the news about the fallout of the pandemic caused by COVID-19, two pieces of news didn't escape my attention.

The first is an announcement by the foreign minister that more than 28,000 workers who were employed in different countries outside Bangladesh were likely to return soon. The second piece of news was a dip in remittances.

In the journey of Bangladesh from a "basket case" or "test case of development" to a lower-middle-income developing country, one factor that has played an important role is overseas employment.

From a paltry 6,000 in 1976 the number going abroad for employment in recent years has soared to some 7-10 lakh. These, of course, are gross outflows and don't represent the net outflow because nobody knows how many return every year.

The government seems to assume that even taking returnees into account, about five lakh people find employment abroad every year.

There are at least three ways in which overseas employment contributed to the success story of Bangladesh's development. The obvious one is as a source of employment and as a way of relieving pressure on the domestic labour market.

The figure of five lakh can be put in perspective by noting that the new addition to the labour force in recent years has been about 16 lakh.

Second, most of the workers are from relatively lower-income groups (though not from really poor households), and their families usually remain home.

Remittances sent by the workers are usually the major -- if not the only -- source of income of such households, and thus play an important role in meeting their expenditures.

And that, in turn, contributes to the growth of GDP through the consumption route.

Household expenditure on a range of goods and services generates demand for them, which, in turn, creates the impetus for output growth.

Third, remittances have played an important role in building up the foreign exchange reserves to an impressive level and in supporting the current account balance of the country.

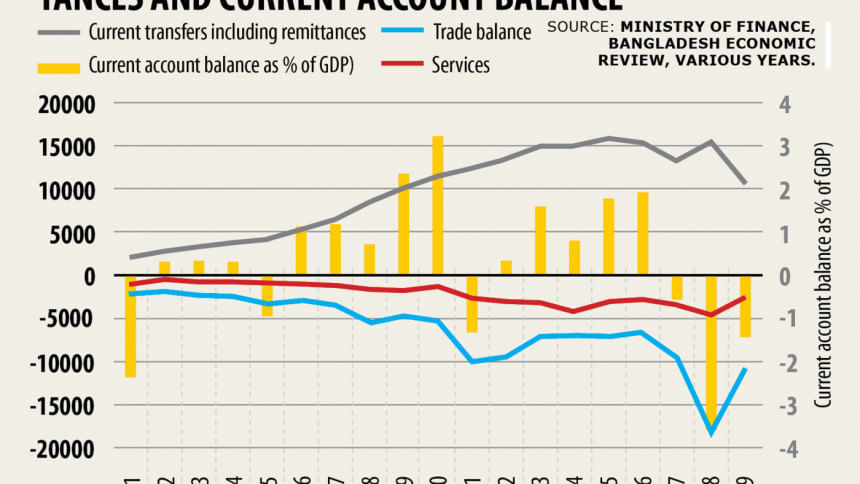

The trade balance (i.e., the balance of exports and imports) of the country is almost always negative. It is the current transfers -- in which remittances are by far the major component -- that help makes up for the negative trade balance.

As a result, the current account balance has been positive in most of the years during the past couple of decades.

But in fiscal 2017-18, there was a sudden steep increase in imports; and as a result of that spike in imports, the current account balance had a huge deficit that year.

Then there was a decline in the inflow of remittances during fiscal 2018-19, which led to a continuation of that deficit.

In the kind of situation mentioned above, what could be the consequences of a sharp decline in overseas employment and the flow of remittances?

On the employment front, it is easy to see that additional pressure will be created on the already fragile domestic labour market.

As pointed out by myself in an earlier article in this newspaper (May 1 2020), about one crore people may have lost their jobs in March-April due to the shutdown of public life and economy.

On top of that, one would have to add the number of workers who will be losing their jobs abroad and will return and perhaps join the labour force.

Although there is no data on overseas employment after February this year, one can surmise that very few were able to get such jobs. And the situation is likely to continue until at least economic recovery starts in the labour-receiving countries.

If the current forecasts of global economic growth made by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are any guide, it can be assumed that the tap of overseas jobs is unlikely to reopen until about the last quarter of this year.

In that scenario, the number of such jobs for the whole of 2020 is unlikely to be more than three lakhs (the total for January and February was 129,127).

If one takes into account the number that is likely to return because of loss of jobs, the net outflow may turn out to be insignificant.

So, the current year is likely to be a lost year as far as overseas employment is concerned.

What was once a reliever of pressure on the domestic labour market is going to turn back and play the opposite role.

Coming to remittances, a survey on their use carried out by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics in 2013 showed that nearly 39 per cent of the amounts received by households is spent on food and clothing alone.

Education and health together account for another 9 per cent or so. The rest is spent on purchasing land or constructing house and repaying debt.

Although it is not known how households would adjust to a sharp decline in the flow of money, one can conjecture that adjustment may take place mainly in the items of consumption outside food.

To the extent that happens, the demand for non-agricultural products (e.g., clothing, furniture, etc.) may decline, which, in turn, may have a dampening effect on their production.

The fallout of the dip in remittances may thus extend to create a negative impact on output and economic growth as a whole.

The possible negative impact of a fall in remittances on the balance of payments of the country has already been indicated earlier.

With the sharp decline in exports that the economy is currently experiencing, unless imports also fall simultaneously, trade balance may worsen further.

In fact, during the July-April period of this fiscal year, exports declined 19.09 per cent from a year earlier. Not unexpectedly, imports also declined.

But if projections made by the WB of a 22 per cent decline in remittances turn out to be true, the impact on the current account balance is likely to be quite severe.

What policy measures can be undertaken in the face of the situation mentioned above?

On the employment front, the issue is linked to that of overall employment strategy that the country should be pursuing; and this is not the place to get into that.

However, a word may be said about the large number of workers who are already returning and are likely to do so in the coming weeks and months.

A full-fledged strategy is required to extend assistance to them in getting re-integrated into the economy.

Given the precarious situation of the economy, it may be more practical to think in terms of helping them start their own enterprises.

Probashi Kalyan (Expatriate Welfare) Bank has to come forward and play its due role, especially by providing credit support to those interested in starting enterprises.

However, speed and ease with which credit is made available would be key to the success of such a programme.

Such an effort is likely to be a win-win proposition for the economy and the individuals concerned.

If properly integrated, the returning workers should be able to contribute to the economy by creating their own enterprises and by generating some employment for others as well.

To minimise the possible adverse effect of a fall in remittance on the balance of payment, the measures that are needed include: (i) all-out effort to put exports back on track; (ii) frugality in imports while maintaining a smooth and speedy supply of intermediate and capital goods needed for reinvigorating production; and (iii) keeping a close eye on payments so that leakage and capital flight do not take place in the guise of imports.

The author is an economist and a former special adviser to the employment sector of the International Labour Office, Geneva

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments