Sustainable development must be financed from domestic resources

Bangladesh faces a significant challenge attempting to achieve and sustain high growth while ensuring environmental degradation is kept to a minimum. As global climate negotiations attempt to elicit commitments from rich countries towards the climate finance pots, countries such as Bangladesh must not forget that the key to long-term environmental sustainability rests largely on their own ability to focus policy attention and allocate sufficient financial resources towards it.

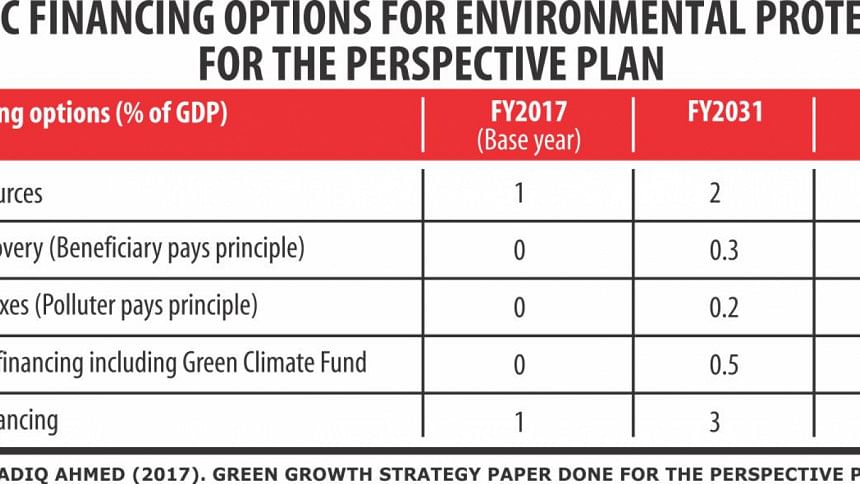

Research done for the Perspective Plan 2041 (PP2041) exercise suggests that in order for Bangladesh to implement a green growth strategy to ensure consistency of growth and poverty reduction targets with environmental protection, Bangladesh needs to increase its spending on environmental protection and climate change related programmes from 1 percent of GDP now to 3 percent of GDP by FY2031 and to 3.5 percent of GDP by FY2041.

As compared to this huge funding requirement, from 2009 to 2016, donor funds directed towards environmental protection or climate change have amounted to around $800 million, which is a mere $100 million per year (0.04 percent of GDP).

Bangladesh played a leading role in helping set up the global Green Climate Fund (GCF) with an ambitious agenda to mobilise $100 billion per year from rich countries by 2020 to finance climate change initiatives in developing countries. As of November 2017, the GCF had raised $10.3 billion equivalent in pledges from 43 governments. So far the GCF has authorised some $2.6 billion in projects globally. Bangladesh got only one project approved so far, the Climate Resilient Infrastructure Mainstreaming (CRIM) project, worth $40 million.

Apart from the very slow progress in mobilising funding, the GCF has reached a road block. The largest donor USA has announced its intention to withdraw from the Paris global environmental accord including the GCF. Additionally, cumbersome procedures in accessing GCF funds remain a major hurdle. In any case, while all efforts must be made to benefit from the GCF, the quantum of funds that Bangladesh will be able to access from the GCF in the near future is uncertain. So an undue reliance on external funds could mean that the scale of funds Bangladesh requires for sustainable development will never be mobilised.

To achieve the development targets of Vision 2041 Bangladesh must make strong efforts to unlock domestic resources towards environmental management and sustainable development. Reliance on domestic funds will provide a reliable basis on which long-term initiatives can be planned and executed. Deploying domestic resources is also the best mechanism to get citizens involved in holding the government to account, as they know that the money being spent comes from the taxes they pay, and not from external sources.

Environmental management suffers from poor resourcing

Direct spending by the coordinating environmental ministry, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), is very limited, increasing from 0.05 percent of GDP in FY2000 to 0.06 percent of GDP in 2016. The lack of a substantial allocation from the national budget indicates, most importantly, absence of a strategic vision and roadmap towards sustainable development. If the MoEF has to be the true custodian of environmental management and protection activities in Bangladesh, the first step is to invest in its capabilities and increase its budget allocation to at least 0.5 percent of GDP by FY2041.

Beyond the MoEF, there are arms of the government that carry out functions critical to sustainable development. Overall public spending of core ministries dealing with water and environment-related services and the water and sanitation component of the local government division (LGD) and local government institutions (LGIs) constitute 1 percent of GDP. Much of the resources come from spending on water, sewerage and waste management funded by the LGD and own resources of LGIs (0.54 percent of GDP in FY2016).

Yet, a spending level of 1 percent of GDP for a country with 160 million people, with a huge environmental protection problem, and rated as the fifth most natural-hazard prone country in the world, speaks volumes about the relative neglect of the environmental protection agenda.

Stepping up domestic financing is feasible

Public financing policies: The public finance constraint on the budget in Bangladesh is well-known. Most public programmes are under-funded. Large infrastructure and human development needs regularly overshadow financing requirements of other programmes. As noted, successful implementation of the green growth strategy calls for a sharp increase in public funding for environmental services from the current level of 1 percent of GDP to 3.5 percent of GDP by FY2041. How can this level of public funding be mobilised? A suggested financing plan is shown in the table.

Overall, some 2 percent of GDP of additional financing will need to come from tax resource mobilisation. Bangladesh has one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios in the world and the 2041 PP Macroeconomic Framework allows for an additional tax-GDP ratio increase of 5 percent that can accommodate this additional financing.

The remaining 0.5 percent of GDP domestic financing can be mobilised through the application of the beneficiary pays principle (cost recovery) and the polluter pays principle (green taxes). Presently, there is minimal cost recovery from water and sewerage services provided by Wasa and municipalities. This imposes a serious financing constraint on the public agencies that in turn limits the quality and quantity of supply. This pricing policy must change, both to mobilise funding for new investments as well as to ensure efficient use of water. The water and sewerage pricing policy must move to full operating cost recovery by FY2020 and 100 percent capital cost recovery by FY2031.

Regarding green taxes, the combination of fossil fuel tax and pollution tax on industries polluting air and water and households polluting water should generate adequate revenues to finance environmental protection and other important transport sector programmes. Emission taxes may be imposed, if legal limits are exceeded, on highly polluting products and sectors. By the same token, incentives must be offered to the use of materials and consumer goods that are eco-friendly. These taxes will be politically tough, but a start has to be made if the government is serious about protecting the environment.

This is also one area where external support in the form of funds to partially subsidise technology adoption, and technical assistance to facilitate technology transfer, and in the design of tax instruments, can be beneficial to Bangladesh.

Private financing options: There are three main instruments for boosting private financing for environment. First, in a number of areas, such forestry for timber, fisheries, eco-tourism, water supply and waste management, private supply can be encouraged with proper regulatory and pricing policies. These are commercial components of the environmental services and many good-practice international experiences exist for boosting private supply in a framework that is consistent with environmental protection. Bangladesh can learn from these experiences and develop proper policies and institutions to attract private investment.

Second, legal and regulatory policies can be used to encourage proper adoption of measures that include private investment in protection of the environment. Important examples include adoption of clean air technology in industries, installation of effluent treatment plants (ETPs) in industries and private hospitals, and prevention of land degradation through proper farming practices including the banning of jhum cultivation while providing alternative livelihoods to the affected population.

Third, the public sector can enter into co-financing arrangements of a range of environmental services through public-private partnerships including partnerships with communities. For example, programmes for clean rural water supply and sanitation, clean-up of rural ponds used for bathing and household cleaning, public toilet and public bathing facilities can all be implemented through public subsidy to private suppliers as well as through cost-sharing arrangements with the community.

Sadiq Ahmed is vice chairman of Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, and Suvojit Chattopadhyay is Bangladesh country manager of Adam Smith International.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments