The costs of industrial protection: who pays?

GHOSTS OF PROTECTION

Protection to domestic industries has been an integral part of Bangladesh's economic policy since independence. This was one policy we inherited from Pakistan times without much thinking. In the 1970s there emerged an alternative path to industrialisation and growth – export-oriented industrialisation.

Success of the East Asian economies—South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore—showed the way. China is an extraordinary example having achieved double digit GDP growth rates for a quarter century on the back of exports. Bangladesh finally moved to embrace the policy of export-orientation and trade openness, albeit gradually and intermittently over the past 30 years or so.

A closer review of the state of industrial protection as it stands today reveals that the ghosts of protection remain alive and kicking, imposing costs on the economy and consumers, in particular. It is the premise of this brief analysis that the burden of protection costs falls unevenly on the consumers in Bangladesh, through high tariff-induced prices of imported consumer goods and import substitutes domestically produced and sold.

THE SURGING MIDDLE CLASS

With Bangladesh's middle class surging in size and spending power consumer goods are in high demand – but at what price? In 2015, a leading international firm, Boston Consultancy Group (BCG), published a report entitled, “Bangladesh: The Surging Consumer Market Nobody Saw Coming.”

The report focused particularly on the middle and affluent class (MAC) in Bangladesh, defined as consumers earning more than $401 (approximately Tk 34,000) a month, or above $5,000 annually. This segment of consumers, estimated to be around 12 million strong, provided insights into the consumption trends of goods and services that went beyond basic necessities, and into the realm of convenience and luxury.

Examples include air conditioners; flat-screen TVs; and imported cosmetics. BCG projects the size of Bangladesh's MAC population to rise to 34 million by 2025, when our GDP will have crossed $500 billion.

The BCG report points out that the Bangladeshi MAC population accounts for only 7 percent of the country's population—meager by Asian standards. In comparison, the number stands at 21 percent for Vietnam, 38 percent for Indonesia and 59 percent for Thailand.

Since Bangladeshi consumers pay around 50 percent to 100 percent above world prices for consumer products—either imported or produced locally—this does not seem all too surprising. Why?

BANGLADESHI CONSUMERS PAY HIGH TARIFF-INDUCED PRICES

Consumer Association of Bangladesh (CAB) is now voicing concern that consumers are being left out of budget consultations and any discussion on tariff setting, though they are the ones who ultimately bear the burden of the tariffs. Even on a global scale, Bangladeshi consumers face the highest average rate of tariffs on imports, especially compared to its Asean neighbours, all of whom impose substantially lower average tariffs (e.g. Bangladesh 25.6, Vietnam 9.6, Thailand 10.2, Asean 4.7).

Since tariff rates on consumer goods are typically higher than average rates, Bangladeshi consumers pay some of the highest prices for consumer goods in Asia, if not the world.

MEASURING COSTS OF PROTECTION

Bangladesh tariff protection structure presents a unique case where much of the protection is accorded to producers of import substitute consumer goods. This presents a unique but simple approach to measuring the costs of protection to consumers by measuring the divergence between the international price and the tariff-induced domestic price of protected consumer goods.

A tariff raises the domestic price of the product over the international price by at least the amount of the tariff. As such, it is in essence a tax on the consumer and a subsidy to the producer; in the sense that without it the producer would have to sell at the international price, which is lower. Producers pass on the tax burden to consumers in the form of higher tariff-induced prices including mark up.

Moreover, the higher tariff-ridden prices contribute to restraining imports, and limiting the consumers' choice. PRI research has monitored trends in nominal tariffs and landed cost of imports for over 25 years in order to be able to measure the extra cost to consumers as a consequence of protective tariffs on consumer goods.

Consumers do not just pay a higher price for the imports, but also have to pay an extra cost in the form of higher prices on domestically produced import substitutes, as producers potentially raise prices up to the tariff-induced price.

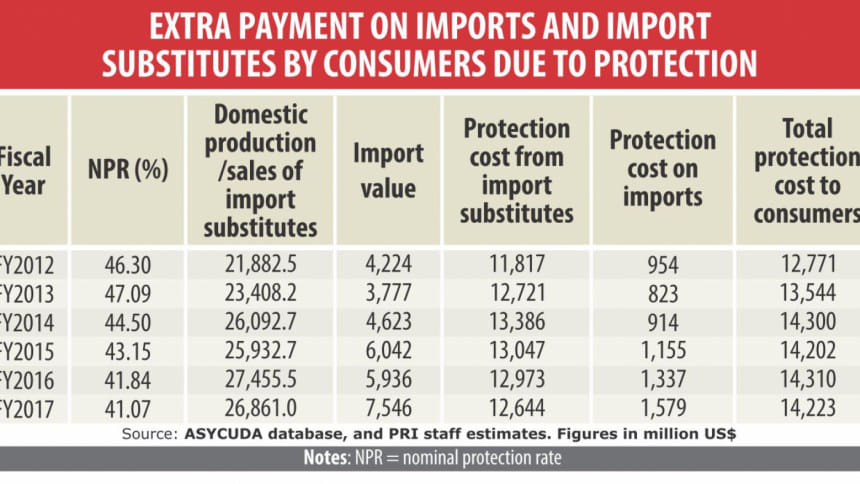

Estimations of the extra cost borne by consumers due to protective tariffs can then be computed by adding up the protection-induced price effect (NPR) – extra cost – on the sum of imports and domestically produced import substitutes.

These costs are then propounded as a proportion of GDP.

The estimate of the protection cost is based on the importation of consumer goods and domestic production and sale of import substitute consumer goods only, excluding automobiles, alcoholic beverages, cigarettes, and firearms.

During the 5-year period, FY2013-17, the total protection cost to consumers works out to a substantial amount of $70.6 billion. For the fiscal year 2017, the protection cost to consumers works out to $14.2 billion (Tk 120,000 crore), or 5.7 percent of FY17 GDP, and 31 percent of manufacturing value added.

This is in essence the extra cost consumers pay over international prices – a veritable transfer of resources from the pocket of consumers to that of producers.

On average consumers paid 70 percent above international prices for buying consumer goods in the domestic market.

NPR is a reasonably good estimate of the price raising effect of tariffs and para-tariffs (i.e. protective effect of customs duty and other trade taxes).

In Bangladesh, research shows that the majority of all domestically produced manufactured products are subject to the highest NPR rate. At present, the consumer products with the highest rate of NPR include air conditioners (156 percent), plastic tableware and kitchenware (113.44 percent), non-leather footwear (113.44 percent), sanitary wares (104.80 percent), etc. – products that have been integral in fuelling the rapid expansion of the brand-savvy MAC population.

CONSUMERS FAIL TO LOBBY

Evidently, when it comes to tariffs, the consumer seems to have no voice. Amidst a plethora of stakeholder consultations pre- and post-budget organised by the chamber representatives round the year, producers put forth various proposals for tariff adjustments, understandably, to raise their profitability which can happen if output tariffs are raised or input tariffs are cut.

Producer groups, of whom there are many, lobby hard to get input tariffs (on intermediate, capital, and raw materials) reduced and output tariffs (on consumer goods) increased as much as possible.

To the extent that producers get their way – and it seems they do – the outcome is skewed in favour of producer interests and against consumer interests as consumers end up paying prices that are significantly above international prices.

This is essentially a protection tax on consumers. But nobody, not even the Consumer Association of Bangladesh (CAB), has raised the issue of how long should consumers continue to be taxed to protect producers. This situation is quite unique for Bangladesh but any discussion is absent from the policy discourse.

RATIONALISING PROTECTION A NATIONAL IMPERATIVE

The strategy of import substitute protection for industrialisation comes at a high price in Bangladesh, paid by consumers who end up bearing the brunt of the protection tax. This could only make sense if it were a time-bound initiative. But theory and practice tells us that that is not how protection works. Once started it takes a life of its own. Besides, import substitution has not given us jobs and growth. Export orientation has. RMG success is not a story of import substitution transiting into exports; it started off as an export industry. Not only is the economy stuck in the quagmire of high protection this policy is also characterised with anti-export bias which is preventing numerous non-RMG exports (some 1400 products in FY2017) from becoming significant export items, thus hampering product diversification of exports.

Amidst the ever-growing demand for consumption, rationalising the protection regime has become a national imperative that can spur domestic spending to fuel growth. It is time for CAB to become proactive on the issue of protection costs, thus going beyond those of ensuring unadulterated foodstuff or proper product labelling.

The writer is the chairman of Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments