David Dowland on BRACU’s first PhD and the significance of equitable exchange

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads. While it is making progress across many fronts, there are issues that continue to persist. The disparity maybe attributed to many factors. However, one of the most significant ones is the chasm in education, particularly in the realm of development.

To that end, the latest PhD programme, offered in collaboration between BRAC University (BRACU) and SOAS University of London, is in the field of political economy of development. Not only is this degree the first of its kind, but it also aims to nurture a new generation of scholars.

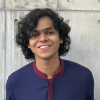

To understand what this prospect means to BRAC University, Campus sat down with Dr David Dowland, the Registrar of BRACU, to get his insight into the possible challenges that the university could face in offering such a programme, the state of academia in Bangladesh, and what pursuing a doctorate really entails.

Campus (C): What excites you about the idea of BRAC University becoming the first private university in Bangladesh to offer a PhD programme?

Dr David Dowland (D): One of the things we've been asked a number of times is the significance of a private university offering a PhD for the first time. It was high time for this to happen. To some extent, the fact that we're able to award a PhD is a sign of the coming of age of some of the private universities here. What's really vital for Bangladesh is that all universities work together in the interest of the country.

Another thing that is very exciting about this particular PhD scheme is that it signals a shift in the kinds of partnerships on offer. Many of the international partnerships that have traditionally been offered are not equitable. Something that SOAS University of London believes in very much, which attracted us, is that you can have a genuine exchange in your partnership. They realise Bangladesh has huge reserves of knowledge and expertise in terms of tackling big issues. So, it's really important that insights from the global South are part of the world discourse. Both institutions awarding the PhD together as genuine, equal partners is a very exciting prospect.

The fee for this PhD programme – GBP 5,515 per year – is the other aspect. This PhD scheme is really flexible. You can do it without leaving Bangladesh by hybrid learning, you can go to London, or you can mix it, but the cost is actually viable for people. We don't yet have scholarships. However, we're going to try to raise some money to be able to offer it. Additionally, we've got lots of faculty members who don't have doctorate degrees but need them. This is a way for us to start addressing that.

C: What are the major challenges that you think the university will have to face?

D: One of the challenges a lot of people point to is how we can maintain quality. SOAS has a very long track record of running PhDs with a robust quality assurance system, which we're going to be using. Before SOAS agreed to a partnership with us, they also did their due diligence to ensure that we were an institution they'd want to work with. We've also had a partnership with them for over 10 years.

One of the challenges that we do need to work on, however, is scaling up into other subject areas and building the capacity.

C: Why is the PhD programme centred around the field of development studies?

D: The field of development studies is about how to improve countries, make them more efficient, and deal with issues such as climate change, poverty, and inequality. This is something BRACU has been working on for years. So, we have expertise in this field that is recognised internationally and has significant partners to work with in the area as well. It is a crucial subject. All big social issues that Bangladesh is facing can be categorised under development studies. Even SOAS, which has huge expertise in this area as well, has a profound interest in Bangladesh and South Asia.

C: Is a PhD programme for everyone? Who do you think should enrol in such programmes in the first place?

D: One of the obvious target markets for a PhD is, of course, people who want to be academics. So, you basically need to have one if you want to have a serious academic career. But interestingly, a lot of people who pursue it don't go into academic life; they go into other areas instead. The types of PhDs have diversified over the years internationally. We've ended up with work-based PhDs of various kinds as well as doctorate degrees in the arts. Many of these will be addressing very current issues in business and industry. So, there's quite a diversity there.

Is a PhD for everyone, though? Certainly not. It's a really big commitment. It takes over your life for several years, and it's costly. It is also costly in terms of opportunities to pursue other endeavours for a while. Quite often, people who pursue PhDs just have a thirst, really. They want to examine a problem or an issue and really get into it. They hope it's going to have some practical impact as well.

C: What do you think the end goal should be when one is pursuing a PhD?

D: One of the personal goals is personally determined. It is important that you get some sense of satisfaction. There's so much pressure now for academics to publish any number of publications to get promotion or recognition. But how many of these publications are useful is one of the questions a lot of them think about.

For Bangladesh, there is a deficit in research. Building up Bangladesh's own expertise in research areas that will be of some national use needs to be a part of the end goal here.

C: PhD holders are expected to contribute to original research. However, the research sector in Bangladesh isn't nearly as good as many other countries. What do you think needs to change here so that PhD holders can commit to Bangladesh-centric research work within the country?

D: People have to see that there are career routes that are designed in such a way that they get opportunities for good career progression; otherwise, they will want to go elsewhere. There also needs to be time for research to be done. If you're pushed to be teaching the whole time, you don't have the time for research, which can be demoralising as well.

Another thing that matters very much is that there's collaboration between different types of universities. If there is collaboration, you can begin to build a research infrastructure in the country. We need to think about subject areas that have a great interest in the country's future. One or two universities working on these areas won't be enough. You need to have a national infrastructure for research. There are also lots of bureaucratic issues nationally. There always have to be rules, of course, but it can be difficult for people if they keep running into all these obstacles.

I think if you're a young researcher, you're looking for a place that's going to be really stimulating. If you've got that kind of environment developing here, people are more likely to stay.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments