The importance of indigenous quota

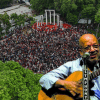

Following the High Court's decision to reinstate the quota system in government jobs, the patterns of public opinion began to take shape once more. Despite the general uproar, the indigenous quota remains especially contentious. Some agree while others don't. But what of the indigenous students themselves for whom this quota is ostensibly designed?

Constitutional provisions are adhered to by the government's quotas for jobs in government that are open to diverse communities. Article 29(1) of Bangladesh's Constitution ensures "equality of opportunity for all citizens in employment or appointment to public service." However, Article 29 (3)(a) empowers the state to establish "special provisions in favour of any backward section of citizens for the purpose of securing their adequate representation in the service of the Republic."

Until 2018, five percent was reserved for ethnic minorities. On October 3, 2018, the government abolished the quota system for government job recruitment in grades nine through thirteen, which also meant the dissolution of the indigenous quota. The High Court's ruling to reinstate the quota system in government posts was overturned on July 21 by the Supreme Court's Appellate Division. 93 percent of civil service recruits should be selected based only on merit – with five percent going to the children of Biranganas and freedom fighters, one percent going to ethnic minorities, and one percent going to individuals with physical disabilities and people of the third gender. This is immediately applicable to all 20 grades of government, semi-government, autonomous, semi-autonomous, statutory entities, and corporations. This means the indigenous quota has been reduced by four percent.

According to Indigenous Navigator, Bangladesh has around 50 indigenous groups spread over the plains and hills. Numerous issues, such as infringement of their land rights, forced displacement, lack of access to essential services, poverty, and political marginalisation, have an impact on their quality of life.

Khingmokay Marma, a fourth-year student majoring in Mass Communication and Journalism at Dhaka University, states, "Honestly, giving one percent of quota equals to not giving it at all. Only one percent for 50 ethnic groups feels as though it is a form of consolation."

According to International Labour Organisation (ILO), research conducted in Bangladesh in 2017, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (ITPs) were allocated five percent of Class one through four government employment. But the research found that about 90 percent of the seats remained empty. Now with the one percent quota, fewer seats are to be held by indigenous people.

The interviewees see the reformation as a quick fix to put an end to the protests, which undoubtedly affects them.

"I have no positive thoughts on this. To me, it appears that an injustice has occurred. There is already a paucity of representation for indigenous people, and quotas provided an opportunity to assure representation, which has now been squandered as well. Whose interests are served here? The interests of the underprivileged are not being served. No changes will occur with the one percent," says Hritu Roy, studying at the Department of International Relations at Dhaka University.

For some, the quota system is a lifeline; they see in the quota system a chance to assert their place in a society that too often overlooks them. To the indigenous people, it is a form of affirmation that the state acknowledges its duty to protect a vulnerable group.

Khingmokay further says, "We need indigenous quotas because we are lagging behind. If someone from an indigenous community gets a government job in a higher position with the help of the quota system, the person may represent their community, encouraging others to come forward for higher education. This also helps guide the future generation. Since the abolishment of quotas in 2018, there has been no indigenous BCS cadre except a few, due to which many are losing interest in higher education."

Another indigenous student studying at Dhaka University who wishes to remain anonymous vocalised her discontentment, "Nobody thinks about the minorities. We are fighting for survival so that we don't have to flee to other places. Some say there's no need for indigenous quotas after university admissions. How many indigenous people get into universities? Those who get into universities want better lives for themselves. Can't they even ask for that?"

A point that arose while speaking to the students was that the lack of media exposure of what happens in the hilly areas is one of the many reasons why the majority do not think about minorities. They also point out the privilege of the people, which enables them to argue against indigenous quotas.

"The majority often fails to acknowledge the hardships that plague indigenous people simply because the media find no human interest here," the anonymous student adds.

Hritu Roy says her urban upbringing had given her a chance that did not necessitate using the indigenous quota. She says, "I am privileged compared to most people in my community (Chakma). Even though there is a quota facility during university admission, I did not use it, and I think people like me who had a privileged upbringing should not use the quota."

Khingmokay observed, "A person who has been denied benefits can empathise with the difficulties encountered by minorities. We need representation to discuss concerns such as property ownership, evictions, and a lack of qualified instructors and educational institutions. So, I feel that a five percent quota for indigenous people was reasonable."

To ensure representation, the government must take into account their struggles which take many forms. Systemic discrimination includes inadequate access to quality education, healthcare, and economic opportunities, which are frequently compounded by geographical isolation. Culturally, they face marginalisation with their languages, traditions, and identities devalued or actively suppressed. Socially, they are frequently subjected to discrimination and stereotypes that view them as inferior or less capable, which can continue to perpetuate poverty and marginalisation. These kinds of discrimination create an unfavourable environment in which indigenous people must constantly manage barriers that others do not face.

To ensure a nation's growth, the struggles of minorities cannot be overlooked. True progress is inclusive. Concentrated development, while beneficial to some, ultimately falls short of nurturing a thriving, equitable society. By providing opportunities for education and employment, the quota helps to empower indigenous populations.

Azra Humayra is majoring in Mass Communication and Journalism at the University of Dhaka. Find her at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments