Constructing a conscious change

Every other street in Dhaka city today has a building or two under construction, not to mention the flyovers that are being built. It is a wonder how construction workers carry on with their jobs, without safety nets or taking precautionary measures, even while working at under-construction high-rises. Little do we know about the worker's plight who not only have to toil an entire day for a meager amount, but also sometimes go without proper compensations if injured on site.

Many individuals and organisations have now come forward to fight for the worker's rights and demand better compensation packages for them, not to mention taking into consideration safety measures. One individual has also introduced the idea of training construction workers so that they can keep themselves and others around them safe on construction sites.

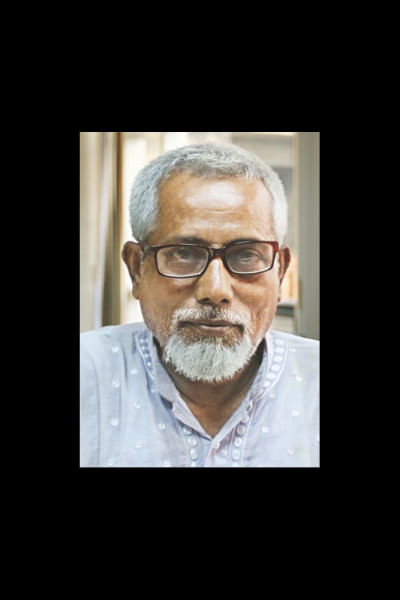

Sheikh Mohammad Nurul Haque is a construction site worker -- "Mistri" as Haque stresses on the Bangla word, roughly translating to a fix-it man who repairs and builds. Dressed in a simple white kurta, Haque, in his late 50s, makes an effort to arrange the newspaper cuttings, labour law documents, training session papers and certificates -- all filed together, while talking about accreditation offered by government bodies. "Construction work is dangerous work," he says. "You cannot see the construction worker, as you would a garment's worker. Here, the risk is higher."

According to reports by Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies (BILS), almost 2,000 construction workers have lost their lives at the construction sites in the last decade. Construction workers have always been working in work spaces that are not safe and very little has changed today.

However, Haque has been organising training sessions for construction workers since the year 2000. "It was only in 2013 that the government acknowledged the training sessions and is now officially offering them to individuals who want to work on sites," says Haque. "I am a proud citizen of Bangladesh. I have always been certain that the authorities would listen to my voice." After the training session, the workers earn a certificate and an accreditation from the government in the form of a Sromik Card. "This card is just like an NID," explains Haque. "Construction workers will enjoy many benefits if they have this card. For instance, children of those with the Sromik Card will qualify for education scholarships. In addition, family members will also qualify for medical fee waivers in many cases."

Haque has also been working as the National Coordinator (construction workers) for the ILO in Bangladesh for the last many years. Before retiring from the post last year, not only did he organise training sessions on a regular basis (which he still continues with help of local funds), but he also worked towards establishing a minimum wage for the workers. The minimum wage for construction workers came into effect on October 2, 2012. "Today, the minimum wage for a first-time construction worker (unskilled worker), working in the cities is 425 taka a day and 375 taka a day for those working in rural areas," explains Haque. "For skilled workers, the minimum wage is 600 taka a day in the rural areas and 800 or more a day in the cities."

For more than a decade, Nurul Haque has been taking steps to bring about small changes in the lives of construction workers and making them better. He has been educating himself about the present labour laws and working with the government to improve and enhance the laws for construction workers in Bangladesh. "Despite all this, only 20-30 percent of positive changes have been made," says Haque. "Everyone has to come together to make a bigger and a stronger change."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments