Corruption – Towards kleptocratic state capture

2013 was a year of lost opportunity in terms of prospect of corruption control, and in fact, much more. It was a year of blatant denials in the face of credible allegations of high profile corruption. Corruption continued to cause huge loss to the economy and unbearable burden to the common people. We also saw how corruption killed people. Corrupt forces gained more influence and power in the policy and governance structure. It unleashed a shameless picture of questionable accumulation of wealth of people in positions of power inconsistent with legitimate sources of income. Ever-increasing premium of holding power reinforced the zero-sum game of politics. To cap it all, indicators of kleptocratic state capture have taken deeper roots.

At the end of this last year of the tenure of a Government that came to power with anti-corruption as one of top priority pledges that ensured it a huge popular mandate, one can also recall some positive efforts that were taken. The Parliament, the key institution of democratic accountability, started off well. While in the eighth parliament forming of parliamentary committees took over 18 months, the present ruling party can claim some credit for forming all such committees in the very first session after election. Some committees have been active, though conflict of interest remained a key predicament against delivery. Expectations of an effective Parliament were further shattered from the very first session due to boycott by the opposition, who abstained from about 90% of working hours of the House.

The right to information act 2009 was passed in the first session, followed by the protection of information disclosure act in 2011. If effectively enforced, these could go a long way in corruption control. Among other positive initiatives were anti-corruption training of officials in institutions funded by public money; second generation Citizen's Charter in public service delivery institutions; local level IT-supported information centres; and introduction of e-procurement, limited though. These could have opened opportunities for corruption control in service delivery in relevant sectors.

Consistent with commitment as a State Party to the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), the anti-money laundering capacity was strengthened, which helped Bangladesh's membership of the Egmont Group. For the first time a success has been achieved in repatriation of stolen assets. The National Integrity Strategy has been adopted raising expectations that key institutions of accountability could move to higher levels of accountability.

However, prospects of genuine results have been severely damaged by corruption-friendly acts and initiatives that weakened the national integrity system. Independence, integrity and effectiveness of administration, law enforcement agencies and justice system have continued to be undermined by partisan political influence.

The government has shown just before the end of their tenure that it was committed to underperform against their own election pledge. The Anti-corruption Commission Amendment (2013) bill has imposed a mandatory provision on the ACC to secure prior government permission before filing any case against public officials including judges, magistrates or public servants for alleged corruption. Imposition of this unconstitutional and discriminatory provision in a deceitful way that included securing the President's consent in the darkness of night has practically converted the ACC into a toothless and clawless fat cat. The only silver lining is that the former Law Minister who now holds the position of Adviser agreed in an event on the sidelines of the Conference of States Parties to UNCAC held in Panama City that passing the act was a mistake.

According to the annual corruption perceptions index of Transparency International, Bangladesh received 27 points this year in a scale of 0-100, one point higher than last year, which is the same as in 2011. No room, therefore, for complacence, especially when we remain far below the global average score of 43, indicating the corruption continues to be a critical challenge for Bangladesh. More disappointingly, although our ranking has improved from 13th from below in 2012 to 16th, we have remained the second lowest among South Asian countries, better than only Afghanistan.

On the other hand cost of corruption has continued to grow alarmingly with a particular bias on the common people with modest means. The National Household Survey 2012 released on December 28, by Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) showed that 63.7% of the surveyed households have been victims of corruption in one or other selected sector of service delivery. Most important service delivery sectors affecting people's lives such as law enforcement, land administration, justice, health, education and local government, remain gravely affected by corruption.

In terms of implications measured by the amount of bribe, the situation has worsened. In 201, cost of bribery in the surveyed sectors was estimated at 1.4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or 8.7% of annual national budget, which has risen now to 2.4% of GDP and 13.4% of annual budget. The survey also shows that while corruption affects everyone, the poorer sections of the society suffer more. Cost of petty corruption was estimated to be 4.8% of average annual household expenditure. More importantly, for households with lowest range of expenditures the rate of loss is much higher at 5.5% compared to higher spending households for whom it is 1.3%. In other words, the burden of corruption is more on the poor.

That corruption adversely affects development prospect has been a commonplace wisdom. It is also well-known that corruption undermines democracy and deprives people of fundamental human rights. Pervasive corruption erodes trust in leadership and democratic institutions. Corruption has continued to make access of the poor and disadvantaged to the whole range of basic services and entitlements like education, health, and nutrition and safety-net conditional upon their capacity to make unauthorized payments. For public sector employment seekers bribery and/or partisan political linkage have become more important credential than merit, experience and expertise, which has caused deep frustration and despair in the society. Especially for the job-seeking young generation bribery has become the key challenge.

On the other hand the Rana Plaza tragedy of April 24, 2013 showed us graphically that corruption also kills innocent, honest, diligent and hardworking women and men striving to eke out a living. That corruption is the key factor behind deaths of more than 1200 lives was clear enough. The building was allegedly constructed in an illegally occupied piece of land in collusion with the powerful from both sides of the political spectrum, supported by commission or omission by officials in the municipality, Rajuk and other authorities whose responsibility it was to ensure compliance to laws, regulations and codes. There were gross violations all around by abusing power or by illegal transactions.

That corruption kills people has also been blatantly manifested by numerous deaths that have occurred in internecine violence and fights between factions and sub-factions even within the ruling party at local levels for capturing public tender and contracting and grabbing of land, water bodies and market places, in many cases with blatant impunity. According to one report, in Bogra alone at least 30 people lost their lives in such violence.

Political affiliation has been reaffirmed with greater vengeance as the only viable credential for securing permits to set up business enterprises in such sectors as banking, insurance and media houses. That the power of corrupt money can guarantee impunity in the face of blatant violation of laws, regulations and codes thanks to a pernicious collusion of politics with business, administration and law enforcement, is clear enough.

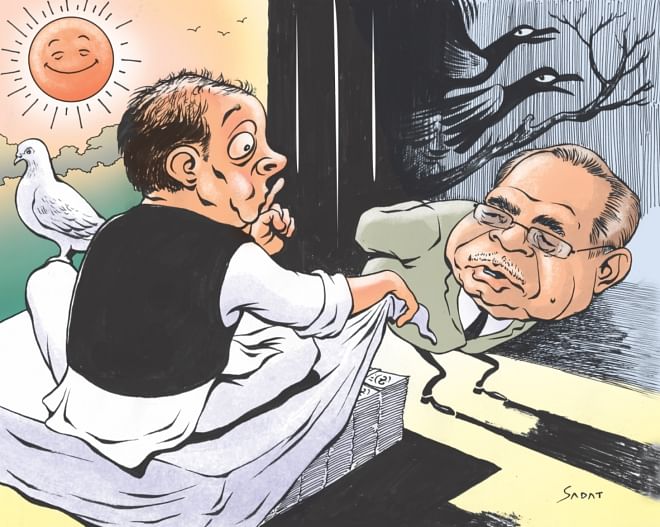

We have been deeply concerned time and again that the ratio of MPs with business as primary occupation has reached nearly 60 percent from about 18 percent at independence which has rendered politics difficult for true politicians. By the end of the year we have also seen, thanks to the disclosure of assets of candidates for parliament election, even more disappointing and indeed extremely disconcerting picture of how power is abused to amass wealth disproportionate to known source of income.

Allegedly, aggrieved by the disclosure, a section of 'political leaders' rushed to the Election Commission to coax it to thwart the prospect of such public scrutiny of the politically exposed persons (PEP) entrusted with prominent public function. If not deterred by public outcry, the Commission was also reportedly going to explore the possibility of complying with this illegitimate and illegal demand which could also constitute contempt of court.

Powerful ministers defended adamantly that there was nothing wrong in amassing wealth from positions of power, reflecting the denial syndrome that has determined government policy stance vis-à-vis corruption throughout the year. They did so with regard to alleged conspiracy to corruption in the Padma bridge project that gave the World Bank the opportunity to 'chop off the head for headache' and withdraw its lending for the project.

The same denial syndrome damaged the prospect of any firm and effective action against those responsible for share market collapse and scams in Sonali Bank, Basic Bank and other publicly owned banks. Nothing happened with respect to the scandalous recruitment business in railways nor did the government show any firmness to act in view of allegations of irregularities in such big procurements as DEMU train even though the Planning Commission found “shoddy” work. Concerns about lack of transparency in defence purchases have not drawn any meaningful response either.

The list is far from complete. But the icing of the cake came, as already mentioned, in the form of reports on incredible accumulation of assets allegedly disproportionate to legal source of income by a large section of PEPs. It has only reaffirmed how brazenly office of politics, public representation and Government is taken as office of profit by abusing power.

The state structure has clearly been exposed to kelptocratic capture by those who benefit from corruption at the expense of those who would like to control it. By the end of the year, it also became clearer than ever before that one of the main factors behind the ruthless zero-sum game of power-politics with public interest and people's life, liberty, safety and security as victims is the sky-rocketing premium of winning election which makes remaining in power or going to power as indispensable as narcotic dependence. On the other hand losing power is not only perceived as being deprived of the premium, but also being exposed to higher and higher levels of risks including threats, intimidation, imprisonment, enforced disappearances, again by abuse of power.

Due to this growing linkage of power politics with corruption it is indispensable to explore ways of resolving the election-centric crisis from a more comprehensive perspective of fundamental reforms to break this linkage. Failing to cope with the corruption-related risks for the future of democracy, public interest and accountable governance can be much more menacing than we have seen.

The writer is Executive Director, Transparency International Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments